They do say a picture is worth a thousand words. If there is any mathematical credence to that supposition attributed to celebrated early 20th-century American journalist and newspaper editor Arthur Brisbane, then Erez Kaganovitz has millions of words to his name.

“I have photographed over 2,000 people in Israel,” he says when we meet up for coffee and a chat in Jaffa.

As the rain teems down on the café awning, he tells me how he set out to enlighten folks around the globe about what he calls “real Israel.”

“From my experience, there is something about the human story with which people can identify,” he posits.

Over the past decade-plus, the 40-something Tel Aviv-based photojournalist has accrued an abundance of experience in the field, crossing paths with all sorts of people of all ages and walks of life, proffering an empathetic ear and allowing them to unpack and offload some of their existential baggage in as comfortable and accommodating a setting as possible.

Kaganovitz’s ongoing odyssey into the highways and byways of the mind and heart began in 2012 when he launched his Humans of Tel Aviv project. That was soon followed by several offshoot ventures, such as Humans of Israel and Humans of the Holocaust. The latter, fittingly, also appears on the Humans of Tel Aviv website in German. And now, sadly and inevitably, the site also features Humans of Israel – 7th of October.

There were a number of motives for the initiative, including adding a down-and-dirty street-level perspective to the generic and often sensationalized mass media output, designed to catch the eye for as long as the reader’s virtual communications era-impaired attention span permits, regardless of actual content. But Kaganovitz wants us to tarry for a while and consider the very real-life backdrop of his subjects.

“I think people get the common denominator factor in the stories, and they get the story behind the headline. We live in a time when there is so much information and so many headlines. Every newspaper and everyone who tweets on Twitter floods us with information.”

The idea was to dig into, and beneath, the white noise veneer. Hence the “Humans of” vehicle.

While the idea for Humans of Tel Aviv was kick-started by the innovative Humans of New York scheme – with the Tel Aviv photographic undertaking becoming the world’s third such individual urban-pictorial pursuit – Kaganovitz says the snapping plan was actually inspired by his many forays to pastures overseas and by negative responses he took on from mass media-fueled consumers abroad.

“I have traveled around the world and, for some reason, people didn’t think I was from Israel. Perhaps that is because of my [American-leaning] accent, which I acquired from watching endless episodes of Seinfeld and Friends,” he chuckles. “People thought I was American.”

All would be fine and dandy, he says, until his interlocutors learned his nationality.

“They’d start making faces. People don’t really know Israel or Tel Aviv. The first five minutes of the conversation were nice; and then, when I told them I am from Israel, they’d start talking about the [political] situation here.”

It was as if Kaganovitz was being held personally responsible for the region’s woes.

“The conversation would come round to wars, that people are exploding in Israel, BDS, and that sort of thing. I realized people did not really know Israel and the complexity of society here.”

A dozen years on, Internet users around the globe can now get a better idea of what makes people tick in these here parts, and of the multi-stratified local human condition spread.

“People abroad would principally hear about us in the context of wars and conflict. I thought that if only I could bring all those people to Israel, they could see with their own eyes what the thing called Israel is.”

With that mindset in place, Kaganovitz was keen to avoid clichéd takes such as “Arabs and Jews sitting around eating hummus together” or “Some of my best friends are Arabs.”

“I just wanted to show the complexity of this place, and the multiculturalism.”

Practicalities naturally swung into view, and the Mohammad-and-mountain rapprochement allegory came through. If he couldn’t bring everyone here, perhaps he could offer the world some insight into some of the individuals behind the “Israeli” tag.

Kaganovitz began pounding the beat, approaching passersby on the Tel Aviv streets and simply asking them if they’d like to be photographed and possibly even add something of their own personal story. In this age of social distancing – not the COVID-19 constraint but the alienating fallout of social media, texting, et al – that sounds like a challenging proposition. Can one just stop people in the street and suggest snapping them and chronicling a snippet or two of their life? Presumably, Kaganovitz made sure he had the requisite communication skills and tact before he set out.

“I think I have an advantage because I don’t look very threatening,” he laughs. I got that from his almost unwaveringly sunny disposition. “I also generally smile,” he adds a little superfluously. “And I think we live in a generation in which everyone wants their 15 minutes of fame, and everyone wants to share their story.”

That is surely a given in these times. Then again, out there in the real world, we tend to withdraw into our own space, with our faces glued to cellphone screens and/or keeping our surroundings at bay with earplugs.

Kaganovitz believes there is a real hunger to spill the personal beans.

“If you are genuine and you really take an interest in a person’s story, they will want to share it with you.” Kaganovitz is the living, prowling, documenting proof of that, even when the individual’s narrative meanders through rocky emotional terrain.

That brings us round to the burning issue of the October 7 project as Kaganovitz’s drive to tell the stories of the survivors of the Hamas attacks and of those close to the victims – and get them out there to the world – kicked in.

It took a while. “I got going with this some time in November,” he recalls. “It took me some time to get over the initial shock.” Like the rest of us.

The years of relaying human vignettes stood Kaganovitz in good stead as he got to grips with accounts of chilling – and inspiring – events that took place right here, in our own national backyard, and which were, and remain, so fresh.

“As the stories mounted up, I felt I just had to tell this story. The thing that astounds me about this project is that I am telling the stories of ordinary people. These are just people who woke up one morning to a crazy terror attack. They demonstrated amazing resourcefulness and resilience. Those kinds of situations push people to their limits.”

The individual stories

That may or may not be the case; people act differently in given predicaments. Their psychological makeup, emotional baggage, and circumstances may dictate the way they react. That comes across in the individual stories Kaganovitz got down, in both visual and textual form.

One of the most dramatic and heart-wrenching slots features Ruth Haran. The first two epexegetical lines directly below her tasteful and evocative portrait on Kaganovitz’s website read: “Holocaust Survivor and Survivor of the 7th of October Massacre.” That, you might have thought, says it all in the most succinct and dramatic of forms.

But there’s more. We read about Haran’s childhood Holocaust experiences in Romania and across Nazi-occupied Europe. Then we learn that numerous members of her extended family were taken hostage by the Hamas terrorists on Oct. 7. Thankfully, most have since been released, but one is still in Gaza.

And there is Haim Jelin, a survivor from Kibbutz Be’eri, who says: “This was a holocaust right outside our doorstep.” He adds: “The stories are piling up and the silence is deafening.” True to his positive view of life, Kaganovitz quotes Jelin declaring: “You can destroy houses, destroy infrastructure, but you cannot kill our spirit.”

That is evidenced, in no uncertain terms, in the account of Rami Davidian, a farmer from Moshav Patish.

“He drove into the battlefield area numerous times, and he rescued so many people. These are people who are not part of the armed forces, just ordinary people who carried out incredible acts of bravery. We need to tell these stories.” Davidian is one of many heroes whose valiant efforts can perhaps help shine a little light on these dark days and give us some hope for a better future.

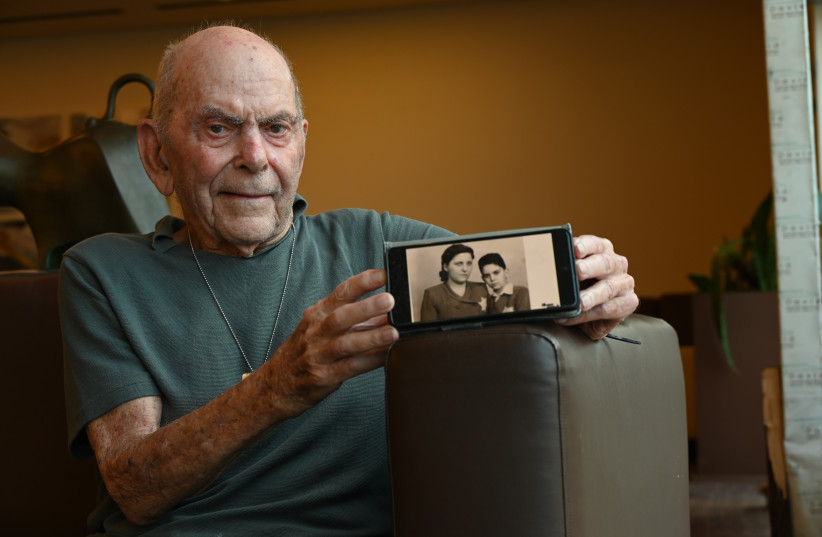

Haim Raanan, from Kibbutz Be’eri, is another Holocaust survivor Kaganovitz photographed who came through Oct. 7 in one physical piece.

“I never thought that, as a Holocaust survivor, I would need to hide for my life again,” he starkly declares. Raanan says the attack on his kibbutz was a worse experience for him than his childhood in Hungary.

“During the Holocaust, I didn’t know personally the 6,000,000 who perished. But in the Kibbutz Be’eri massacre, I knew almost every single person who was murdered that day.”

In his picture of Raanan, Kaganovitz tastefully and sensitively shows the 88-year-old kibbutznik holding a black-and-white photo of himself as a child with his mother.

The difference

Despite his years of photographing and listening to people with weighty bios, Kaganovitz says the October 7 project was a very different and more challenging endeavor.

“There is a big difference between reading the stories in a newspaper or watching them on the news and being there, boots on the ground. Taking pictures of Haim Jelin in the burned-out ruins of the houses, listening to what he had to tell me, and later, walking around Be’eri and taking photos, as a photographer you think about composition and lighting and that sort of thing.”

He managed to hold himself together as the consummate professional, but reality eventually struck.

“It was only that night, after I got home, that it began to sink in, where I’d been. That was tough. I am a photographer, but I am a human being like everyone else.”

People, naturally, have a full right to their political opinions and their thoughts about the ongoing violence in Gaza, but it is simply unconscionable to criticize the actions of the IDF and the Israeli leadership without, at the very least, recognizing the barbarity of the murderous Hamas attacks on helpless civilians. Perhaps Kaganovitz’s efforts to tell the stories of the survivors down south, in the most compelling and accessible way, will help to redress that imbalance and generate a more human and humane line of thought.

In addition to his online work, he is also lining up exhibitions at Harvard University and other major spots around the United States and Europe. That should help his cause.

“We need better perspective, to put things in their right proportion,” he says. Well put.

For more information: humansoftelaviv.co.il/