Shira Chernoble’s mission is to help people be less afraid of dying.

Now 73 and a longtime resident of Tekoa in Gush Etzion, Chernoble works as a death doula. Just as a birth doula guides the birthing process, a death doula guides the process of dying.

Chernoble describes a death doula as “someone who can be there with another person who is dying, without being afraid of the emotions that come up in people, someone who can be comfortable in that journey, who is able to listen and offer [support or assistance] when something is needed.

“A death doula will hold somebody’s hand, be honest with them, have patience and a belief that there is something beyond here.” A death doula must “not be afraid to be honest with people.”

To be successful, a death doula must “give people comfort and support, to enable someone to move on to wherever they need to go. You have to have some kind of belief in something greater than yourself, to do what I do. I believe God is good. I have to trust that God knows what He’s doing.”

"You have to have some kind of belief in something greater than yourself, to do what I do. I believe God is good. I have to trust that God knows what He’s doing."

Shira Chernoble

A house of secrets and sadness

CHERNOBLE IS a child of Holocaust survivors. “I grew up in a house full of secrets and sadness,” she recounted. “I grew up with such pain because of my parents. They were incredible people and they hurt a lot.”

She was raised in the German-Jewish neighborhood of Washington Heights, where the Holocaust loomed large.

Despite the fact that her paternal grandfather was a rabbi and the family attended a Conservative synagogue, “Judaism was not really talked about in our home. I knew I was Jewish, but nothing really made sense. I couldn’t understand a God who killed all these people.

“I was a real rebel. I really wasn’t a great daughter, but it came from having a difficult childhood,” she confessed. “I was always a searching person.”

Chernoble spent time experiencing other religions before exploring Judaism. Trained by nuns as a pastoral counselor 50 years ago, she shared, “They were the ones who made me search for my roots. That’s how I began my journey to Judaism.

“Everything was a secret in [my childhood] home. It wasn’t until I trained as a pastoral counselor that I heard about [the work of] Kübler-Ross. That made me realize that [death] didn’t have to be such a secret. That was the beginning of the change in my life. I learned that you don’t have to keep secrets. I learned that dying doesn’t have to be a lonely experience.”

Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who died in 2004, is best known for her pioneering approach to the terminally ill and to inspiring new approaches to death and dying.

CHERNOBLE’S BRAIDED career as a massage therapist, an expert on essential oils and a death doula offers her a singular perspective on how people live and die. “Today’s world is so technological. Everything is so fast. People expect people to move fast with whatever pain they have.

“People are lonely and feel left out of the world of bereavement and touch. They aren’t being acknowledged, that their feelings are okay. They are left with a sense of being lost, expected to [quickly] get on with their lives. There is no respect for the time people need to heal. But people need to be listened to.”

And that’s where Chernoble’s sanctified work comes in. “I listen, support and help. A lot of times, people can’t verbalize how they feel, and massage allows people to release pain. I’ve always used oils in my massage therapy. I always carry oils with me when I work with people who are ill.”

She’s a passionate advocate of essential oils made by doTERRA. “In doTERRA, I found an oil I could trust. I know the processing is pure. Because of that, the oils work to heal people physically, emotionally and spiritually.”

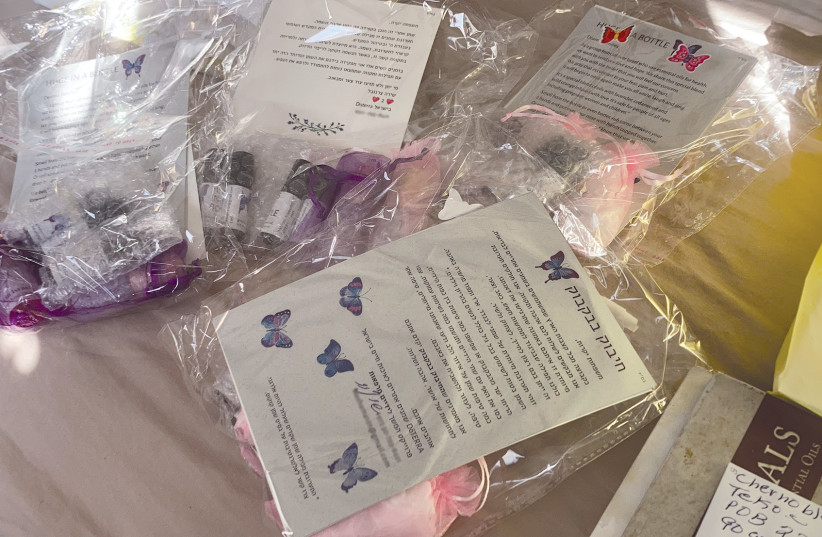

One of the projects closest to Chernoble’s heart is Hugs in a Bottle – a small bottle of essential oil, packaged with a loving note, which she distributes for free to people from all over the world whose lives have been touched by trauma. The letter that accompanies Hugs in a Bottle has been translated into many languages.

To date, she has distributed over 3,000 Hugs in a Bottle. “My dream is to touch everybody in the world. [The gift] is saying they are important, cared about and respected, that they are not alone. I want them to feel the love that I’m sending them. This is the greatest gift in the world.”

Chernoble also created her own blend of essential oils based on ketoret – the biblical incense mixture. She explained that Aaron, the first high priest, used ketoret, which could be smelled far away from where it was burning, to heal plagues.

She calls this special blend Neshama oil, named for the Hebrew word for the soul. “Neshama oil is much more potent than Hugs in a Bottle. It allows me to give people comfort and support that they can use on themselves. Neshama oil is plant-based and absorbed immediately into the system.”

A recent client shared that “Neshama oil has been essential since the loss of my beloved grandmother at the age of 105. The oil allows me to remain grounded, aware, and comforted through this grieving process. It has allowed me to experience energy differently, and assists me in feeling closer to the memories, the comfort, and eases the sorrow as I deal with this massive loss.”

Chernoble, mother of four and grandmother of 12 (and counting), lost her husband, Jonathan, two years ago. “When my husband was sick, we had family meetings to discuss how we could give the best to each other. We had no secrets.

“The last act of kindness I did for my husband was to put a pillow under his head. He was such a supporter of my projects. I feel him helping me even now,” she shared. “When my mother was dying, I wasn’t the greatest daughter. My taking care of my husband was making living amends to my mother.

“After my husband died, I kept finding little red hearts everywhere. I knew it was my husband. That’s the language of the world of death. No words, but there is expression. You have to learn that language, if you want to communicate. You have to learn the language of the world of heaven. That’s real.”

She has some advice for people who are escorting a loved one to the next world. “It’s really important to remember that even if people aren’t conscious, they hear everything that’s going on in the room. The sensitivity of people who are dying is much more clear.”

During the height of COVID, Chernoble said, “I was aware of how afraid people are of dying. Society doesn’t know how to deal with death. People are afraid to talk about it. The fear level was much, much higher, as was the loneliness.”

After so many decades working with the terminally ill and grieving, Chernoble expressed disappointment that attitudes toward death have not changed much. “I thought it would have been more advanced than it is. People are still so afraid. I hope that people can be more open to this kind of experience, this kind of [open] talk [about death].”

Chernoble shared some final words of advice: “It’s really important to know that we all can die at any moment. We have no idea what the next day or moment will bring. I hope people try to be at peace with their loved ones, be at peace with life.

“Live the day as best you can,” she encouraged. ❖