About 10 years ago, Sherri Mandell got a phone call from a total stranger in California. His name was Todd Salovey and he’d come across her National Jewish Book Award-winning The Blessing of a Broken Heart.

“I just read your book and it really moved me,” the playwright told Sherri. “I’m a director and professor at UC San Diego and I’d love to make your book into a play.”

The book details how Sherri, with the support of her family and community, coped with her grief after terrorists fatally stoned the Mandells’ 13-year-old son, Koby, and his friend Yosef Ishran in a cave near their home in Tekoa in May 2001.

Salovey’s one-woman stage adaptation was performed over the course of five years on the West and East coasts of the United States, winning an Edgerton New American Play Award in the process.

In January, The Blessing of a Broken Heart is coming home.

Produced by the Jerusalem-based Theater and Theology company, the show opens January 11 in the capital’s Khan Theater and will travel to Gush Etzion, Beit Shemesh, Ra’anana and Modi’in.

“It’s been 20 years since Koby’s murder, and a lot of people don’t know the story,” noted Sherri on a video call, seated beside her husband, Rabbi Seth Mandell.

That story is likely to resonate deeply with an Israeli audience, especially those who experienced the blood-soaked Second Intifada that raged between September 2000 and September 2005. Koby and Yosef were among more than 1,000 Israelis killed and thousands injured.

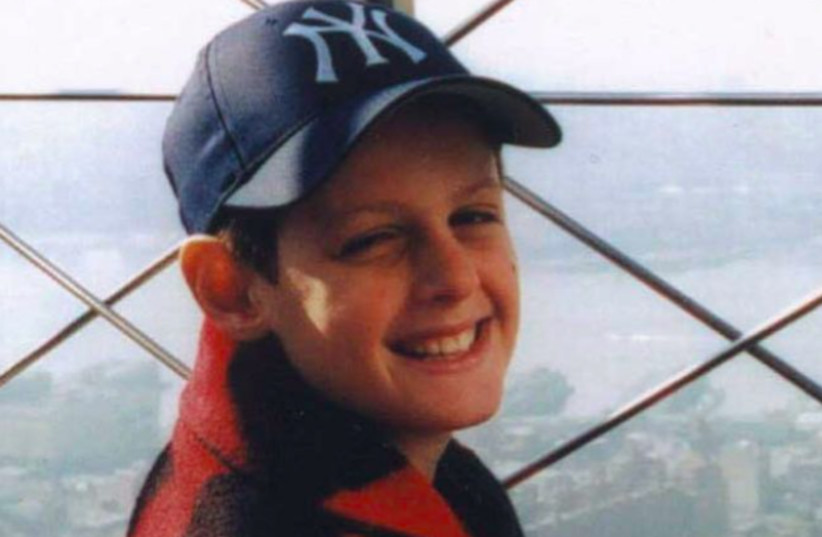

In many ways, Koby became the face of the intifada for American Jews because he was a child – an American-Israeli child. Before the Mandells relocated to Tekoa about five years before the tragedy, Seth was a campus Hillel director at Penn State University in Ohio and at the University of Maryland.

“When Koby was killed, his picture was on the front page of almost every newspaper in America,” Seth said. “The picture showed him wearing a baseball cap. He was identified as an American boy whose hero was Cal Ripken. The event brought home the emotional connection of the intifada to American Jews. We all need individuals to connect to, and he became that person for a lot of people.”

The Jewish response to pain

Their connections in the East Coast Jewish community helped the Mandells channel their sorrow into positivity through the establishment of the Koby Mandell Foundation.

Intended, in large part, “to keep Koby’s power in the world,” said Seth, the foundation offers year-round camps, retreats, support groups and other therapeutic programs providing emotional, physical and spiritual healing for bereaved Israeli families.

The foundation’s work provided a tangible way for American Jews to embrace their Israeli peers at a critical time.

When The Blessing of a Broken Heart was made into a play, “we already had a following because of the foundation, so it was easy to find people to support it and help arrange performance venues,” said Seth. “American Jews were moved by the play.”

The cave is a central symbol in the story as Sherri emerges from the tragedy and the intifada. Her story is layered with the Talmudic tale about Rabbi Shimon Bar Yochai emerging from a dark cave after 13 years of hiding from Roman persecutors.

Another prominent symbol is birds. In the first year after Koby’s death, Sherri experienced strange episodes with birds.

“They fell at my feet, they knocked into my head, they got caught on my windshield,” she said. “I felt like I was a spiritual detective that year with the birds, trying to figure out what it all meant.”

Eventually, Sherri learned the kabbalistic concept of a supernal bird’s nest containing pictures of the two fallen Holy Temples and all the children who died in sanctification of God’s name.

The book and the play convey how Sherri’s faith became stronger over the course of her mourning.

“Sometimes we’re given these horrible tragedies and we’re able to turn them into something tremendously generative. To rise from the ashes and grow. It’s possible to transform the worst things into light,” she said.

“I want people to be informed and ultimately inspired by the Jewish message of ‘choose life and build life and make life great.’ That’s the Jewish response to pain.”

Theater that makes you think

Before the pandemic, Seth and Sherri turned over the day-to-day running of the Koby Mandell Foundation to their daughter Eliana Braner.

That freed up Seth to see about bringing Salovey’s play to the English-speaking Israeli community. Anglos in Israel are loyal fans of Comedy for Koby, the foundation’s twice-yearly benefit show featuring American stand-up comedians in honor of Koby’s love of a good joke. (The next tour is scheduled to begin January 4.)

Someone suggested Yael Valier, creative director of the Theater and Theology company. When the Mandells approached her about the project, they found out she also is a bereaved mother.

“My 21-year-old son, a soldier, killed himself four years ago,” Valier said.

“This has made directing the show heavy for me, but it has also helped me in directing certain scenes because I have confidence in my decisions when the actors are hesitant. If they ask, ‘Can I really laugh?’ I have the confidence to say yes.”

Founded in 2016, Theater and Theology is described as “English-speaking theater that makes you think.” Each performance is followed by a discussion to “dig into the juicy theological issues” raised in the play, said Valier, a 1997 émigré from the US.

“There are multiple theological and psychological overtones to the show,” said Rabbi Dr. John Krug, who handles production design for Theater and Theology.

Living in Jerusalem since 2018, Krug is a psychologist and former dean of The Frisch School, a coed yeshiva high school in New Jersey. He also has about 250 professional production credits to his name, most notably as production assistant and later assistant producer of The Fantasticks for 38 years of the off-Broadway play’s record-breaking original and revival runs.

Krug said that The Blessing of a Broken Heart touches a raw nerve, “almost like looking at a scar from a previous wound. But it’s not a show about grief and mourning; it’s about the resilience of the human spirit. The goal is for people to leave with something to introspect about.”

Indeed, although rehearsals have provoked tears from just about everyone involved in the production, the Mandells hope audiences will feel inspired and transformed rather than depressed.

“I want people to walk out of the play with a sense of the loss we’ve all suffered [from Koby’s death], but also the resilience as we move from the darkness of the cave to the light,” Seth said.

Creating the cave

The part of Sherri Mandell will be played by Jerusalem-based actor and educator Rebecca Sykes.

Valier added a four-person ensemble – Howard Metz, Gillian Kay, Dena Davies and Shifra Levy, chosen from a field of more than 20 people who auditioned – for their ability to “blend together and be very versatile,” and to sing the a cappella songs scattered throughout the play.

“The ensemble members fluctuate between portraying real characters and inanimate objects that highlight what Sherri is feeling. Their bodies and voices augment Sherri’s inner world and represent her outer world,” Valier explained.

When the curtain rises, audience members will watch the ensemble set up the opening scene. One of the four will invite Sherri (Sykes) into the scene to begin the difficult process of remembering and transmitting that memory.

The ensemble then creates a cave that “fluctuates between the place where the boys were murdered and the metaphorical cave in which Sherri finds herself in a place of darkness and constriction and from which she needs to push herself, with great effort and courage, out to the light,” said Valier.

Levy, a 20-year-old student at Ma’aleh School of Television, Film and the Arts in Jerusalem, said the ensemble’s role “is to emote Sherri’s feelings and create a background for her to tell her story, working together to support the main character as she goes through this tragedy.”

Levy also worked on composing the music, which was quite appropriate as she’d cowritten a song with Sherri last year, The Light That Lives On, for the 20th anniversary of Koby’s murder. The song was recorded and made into a video.

The Mandells are now “actively looking for a way to bring The Blessing of a Broken Heart to off-Broadway,” Seth said.

“It’s important for Americans to see the emotional toll that the intifada and terrorism took, and still take, on individual families and the pain it causes. That gets lost in the political rhetoric.”