When art curator Bar Yerushalmi speaks about nourishment, food is not the first thing on his mind. In his Total Nutrition (Mezon Melakhot in Hebrew) art event held in Musrara last month he examined the powerful relationships between food, social class and gender. After all, the larva which is fed the right food gets to be a queen bee (malka).

“We feed each other with different bodies of knowledge,” he explained.

This is a rich statement that flows to several streams. When Yerushalmi mentions nourishment he means more than food. As he sees it, to dress well is one way of offering sustenance to the viewer, who admires the effort. Inspired by an interview with Indian scholar and activist Vandana Shiva (shown at the event), Yerushalmi turned to study our relations with each other.

“When I was a child and learned how to cook from my grandmother Edna Yerushalmi,” he shared, “I understood that she is an endless source of knowledge and flavors.” As he sees it, one can never really mimic the dish grandmother made because there is tacit knowledge in the body; the eye that discerns the heat level of a boiling pot or the hands that deftly fold the dough. This knowledge is irreversibly lost when one succumbs to old age and death. Yet something of it is able to shine across time.

In the screened interview, Shiva argued that “we live in the final stage of a very deceitful system” and urges the listener to ask his or her grandmother to teach them how to cook and to start a garden. As she sees it, human civilization stands on the unrecognized labor of women. Those who give birth and were often tasked with cooking and caring for the family while men were encouraged, she claims, to go to war and plunder.

This claim that powerful forces operate to blind us to what really is the ground underneath our feet, is a potent starting point from which to begin asking questions.

Daniella Seltzer, an activist in food rescue, created Preserve. Wait. Remember. Food rescue means to collect unused produce from markets and bakeries and to offer it to the community in an anti-capitalist act of sharing. The idea underpinning the activity is that nobody should starve if perfectly good food is tossed to the bin daily to keep prices up. During her performance, she invited visitors to taste pickled or salted foods. To preserve food, she said, requires faith in having a future in which to enjoy it. Two Russian-speaking women eagerly queued with the hope to taste the pickled watermelon. “This is like, the most Russian thing in the world,” one of them excitedly told the other, “I haven’t eaten it in ages.”

THE ARRIVAL of roughly one million Russian speakers to Israel in the 1990s was met with hostility by Israelis living in the periphery of the country as this influx of Soviet-educated immigrants competed with them for housing and jobs.

“In a day, half the people working at the Ashdod municipality were Russians,” Marcelle Edery told me as she offered a dish of piquant red tomato-pepper matbukha to those coming in. Her own landlord tripled the rent and she found herself living as a single mother at a public square alongside hundreds of other people in a similar situation.

Now a resident of Musrara, she explained a thing or two about the Mizrahi perspective. “I said: ‘The struggle is not against the Russians, but against the State of Israel’ and this is where we need to direct our efforts,” she pointed out. For five years she led protests, roadblocks and tire-burning. She blocked the road to and from Ashdod port, an important artery that serves the entire country.

The next day, then-housing and construction minister Benjamin (Fouad) Ben-Eliezer arrived and the process of locating public housing for those made homeless started, she said.

Community coordinator Ester Avia Houta had asked the local women to come with red foods to match the performance of “Vordan Karmir” by artist Chana Anushik Manhaimer. Vordan Karmir [literally, Worm’s Red] is Armenian for a dye made from an insect that produces a deep red carmine color.

Facing Edery and offering cold tomato soup, was Nicole Zagury Gafni who suggested I try fougasse, a flatbread typical of Provence in southern France. “I have been living here for 78 years,” she told me, “we know everyone who came tonight.”

Perhaps Total Nutrition could be seen as an attempt to lick the taut skin of the world, the formalistic social structures which shape our everyday lives, from within. What we normally see is the exterior skin, the surface, movie reels of happy Jewish immigrants arriving in Israel from North Africa. When children listen to their mothers and grandmothers they absorb another history – of the transit camps and discrimination – as if from their mother’s milk.

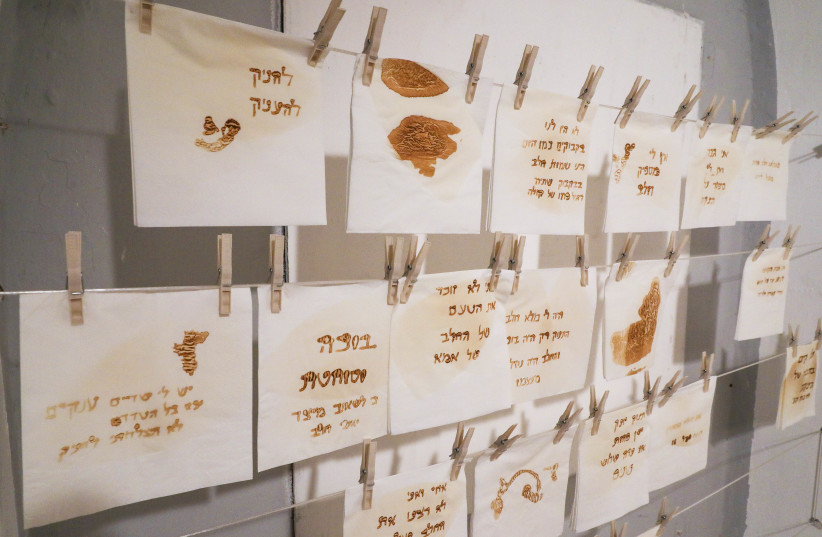

At Nursing Area, artist Liat Danieli explored just that – the first substance most humans put in their mouths. Interviews she conducted with local women before the performance became nursing stories. These are, at times, brutally honest one-liners. “The baby does not want a mother, it wants a tit,” one woman shared. Another expressed her frustration as she had “huge breasts and not even a drop of milk.” Sitting (fully dressed) with what appears to be pumps attached to her chest, Danieli invited patrons (males as well) to share their nursing stories with her. These were added to a wall display of handwritten pages as part of the evening. “When Danieli listens to mother’s milk [stories],” Yerushalmi offered, “she is working with it as material that remembers and preserves memory.”

FOR KUTI and Ruth (not their real names), a couple who came to Jerusalem especially for this evening, “Musrara,” Ruth said, “is a brand which connects people in the art world.” “I am amazed each time I come,” Kuti added.

We wait for artist Hadas Duchan to experience her work What I Held Lasts More Than A Lifetime. In it, she puts on a white robe and offers to examine my hand based on a questionnaire I filled out before stepping in. We discuss for a brief moment the importance of the thumb in human evolution and she offers me a tasty pudding cast from Miss Gafni’s hands. “I am only giving you a finger,” she laughs, “not the whole hand.” The finger arrives with hot chocolate sauce. My professional pride compels me to try it – it is quite tasty. Yet, I am unable to eat something made to appear like a human body part. Something irrational compels me to toss the dish aside.

When I visited artist Chana Anushik Manhaimer, she wore a red costume loosely based on the traditional Armenian halav attire of a long red shirt and used crushed Vordan Karmir to paint on the wall using playtronica to share the recorded voices of local women who live in Musrara. Playtronica means to fuse human movement (closing one’s fingers for example) and sound being produced (a recorded interview).

The costume and intensity of the space made me think of Shamanistic rituals and, seeing the entire evening had been focused on female bodies and knowledge, I thought Manhaimer was painting uteruses. “Really?,” Edery commented when I asked her. “To me, they look like butterflies; all [is] in the eye of the beholder.”

At another active space, artist Bar Eylon created a wooden wonder table that combined a fairy-tale for children with the beauty of a Dutch oil painting. In fairy tales, tables can magically put food on themselves without labor. Eylon invited patrons to eat and drink, gratis, on a unique table of her own design. The wooden surface had “valleys” for hot liquids such as soup and “plains” for mushrooms and vegetables, making it something like a physical representation of the ground and shape of Israel (as food comes from the Earth) or a painter’s palette.

“This work happens because the audience makes it,” curator Ayelet Hashahar Cohen told me. “The next planned event,” she gently reminded me, “is the 21st edition of the Musrara Mix Festival set to start on Tuesday (November 30).

Returning to the Yerhushalmi part of the building I spoke with Musrara student Elior Franco. She pointed out that the real-estate boom in the capital makes it hard for her to believe she will ever be able to afford her own home.

“I will never have enough money to buy my own place,” she told me, “because every American buys a huge building in this city. I feel this is the same story all across this country.”

Luckily, I was able to speak with Houta as well.

“Here,” she said, “the focus is the people, not the food. These women are able to rise above the stereotype of what is a Mizrahi woman. This evening had been able to place them in a place of dignity, with their names in the same font size as those of the artists showing their works.”