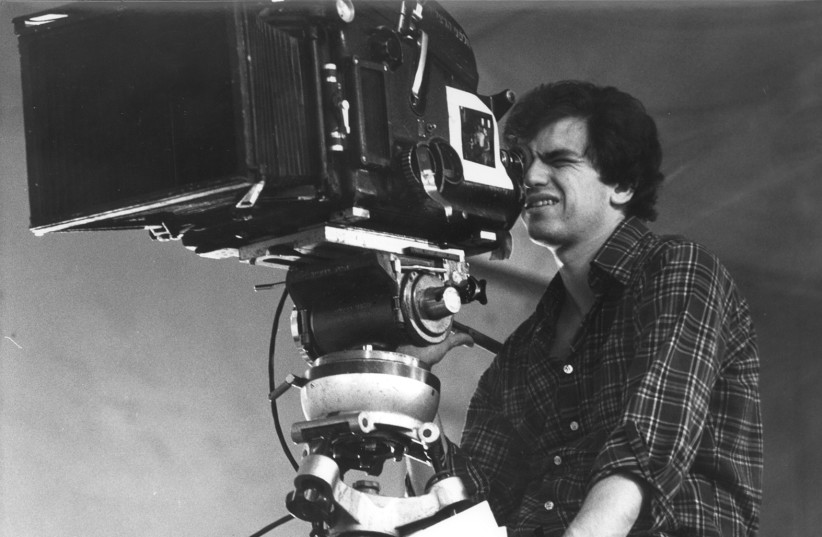

‘My films are very personal without being autobiographical,” says Avi Nesher, Israel’s leading filmmaker, in Nesher, a new documentary by Yair Raveh, the first comprehensive film about his work, which will be shown at a number of screenings at Docaviv, the Tel Aviv International Documentary Festival, which is currently underway at the Tel Aviv Cinematheque until June 1 (docaviv.co.il).

A film critic with the widely read blog Cinemascope, Raveh is also a screenwriter and filmmaker, who has created a brilliant and incisive look at Nesher’s life and work, far removed from the standard biographical documentary about an artist. In Nesher, he shows how the director’s life cannot be examined separately from his work: A portrait of Nesher is a portrait of his films, and vice versa.

Raveh also shows how Nesher’s films, from The Troupe (Ha Lahaka), his first that he made in 1978, up till his most recent movie The Monkey House, which opened last September, paint a portrait of Israeli life – not just the facts of it, but the emotions and experiences behind the history.

Life story

Raveh demonstrates the common threads throughout his movies, showing how he often tells coming-of-age stories that feature groups of young people at decisive moments in history, which reflect different facets of Israeli life and culture.

Nesher, 71, burst onto the Israeli scene with The Troupe, a phenomenally successful film that tells the story of an army entertainment troupe. It is known for its charismatic young cast, which included Gidi Gov, Meir Suissa and Gali Atari; its score, featuring songs that are still popular to this day; and the story of rebellion among the performers that can be seen as a metaphor for youth defying society’s conventions, elements that have characterized virtually all of Nesher’s subsequent films.

He was only 24 and had found a way to make movies about his life and the lives of those around him that reflected a reality audiences could relate to, and he followed it up quickly with Dizengoff 99, a movie about two guys and a girl sharing an apartment in Tel Aviv after the army and trying to make their own movie.

A few years later, he moved on to a complex story about the Lehi underground, Rage and Glory, starring Israeli-Palestinian actor Juliano Mer Khamis, which was also a tale about young people coming of age in a time when some chose to become underground fighters.

Rage and Glory generated controversy, with the Left accusing Nesher of glorifying the Lehi underground, and the Right accusing him of justifying Palestinian terror by showing pre-state Jewish terrorism. “They said I was Fatah. Me, from Ramat Gan?” he recalls, laughing. After this, he moved to Hollywood for a few years, where he made successful genre films, starring such actors as Drew Barrymore, and then came back to Israel in 2001.

RETURNING TO Israeli filmmaking, he released an extraordinary series of distinctive movies looking at all facets of Israeli life starting with Turn Left at the End of the World (2004), about Moroccan and Indian immigrants in a Negev development town. He went on to make The Secrets (2007), The Matchmaker (2010), The Wonders (2013), Past Life (2016), The Other Story (2018), Image of Victory (2021) and The Monkey House (2023).

Nesher opens with him filming The Monkey House in Ramat Gan, near where he grew up, and ends with him taking the podium at its premiere. It is the portrait of a filmmaker who is very much at the height of his creative powers, an extraordinary feat in an industry in which most directors are lucky to have more than one good film, let alone a single good decade. Nesher has had over four amazing decades so far.

Using recent and much older interviews, movie clips, archival material, rare photos, and interviews with Nesher’s collaborators and family members, Raveh examines how his films embody the essences of Israeli identity: how his story is, in many ways, the story of a nation – but one told through quirky, original tales, not clichéd tropes.

“My movies are so Israeli, but my innovation is that you don’t have to use the classic stories; you can use your own stories to tell the story of Israel,” Nesher says.

“For us, who were born at the same time as this society, more or less, the idea of building a society from nothing – it’s a fascinating idea... This is something that engages the imagination,” he says. “To be part of a nation that is trying to invent itself, to write about itself, to screenwrite itself, to direct itself – it’s an exciting idea. And you are invested in this story. You are part of this Israeli story, and it excites you till the end.”

NESHER’S PERSONAL life is intertwined with his films. He tells how he met his wife, the artist Iris Nesher, when she was an extra on Rage and Glory. His daughter, Tom, 27, who is about to release her directorial debut, Come Closer, recalls how she was always fascinated by his work and how he gave her a cinematic education at home, screening movie classics for her.

The saddest chapter in the film comes in 2018, with the tragic death of his 17-year-old son, Ari, in an accident. Nesher speaks about not beginning to understand, even after almost six years, how his sorrow over the loss of his son has affected him.

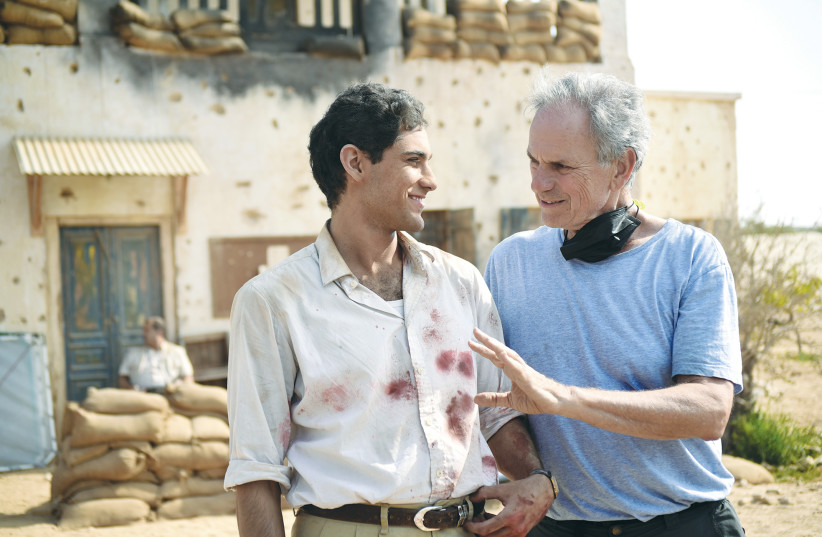

In his first film following Ari’s death, Image of Victory, he wanted to tell a story about young people in the 1948 War of Independence, but felt more keenly than ever the tragedy of the price young people on all sides pay in this conflict. “You can’t tell the story without the other side, two wrongs don’t make a right,” he says.

“The cinematic language is almost a Western – sometimes we’re the cowboys and they’re the Indians, sometimes they’re the cowboys and we’re the Indians – and the only winner is the camera.”

This film, he felt, “carries on a dialogue with my previous films: There it was the young people in the army troupe and here it’s young people on the kibbutz and the young Egyptians – and it’s a coming-of-age film even though it deals with burning historical narratives.” Image of Victory mixes joy and triumph with melancholy and loss.

“In Avi’s movies,” notes Raveh, “at the end most of the time... the characters remain with a broken heart.”

One of the highlights of the movie is an interview with Nesher and his 100-year-old mother Lilly, where they talk about how his parents were opposed to him making a career in movie-making, afraid he wouldn’t be able to earn a living. Nesher says to her, “People have asked you: ‘Why were you against me making movies?’ and you gave a funny answer. You said: ‘How could I know I am the mother of Avi Nesher?’” She nods and laughs.