A collection of family letters written during the Holocaust by Jewish parents to their UK-based children is at the focus of a new art exhibition Ruth Schreiber is set to open on November 7 at the Schloss Sassanfahrt Castle in Hirschaid, Germany.

It is an intimate exhibition that grew out of her communication with Rainer Zeh.

A retired policeman with a passion for local history, Zeh began researching the Jewish presence in Sassanfahrt and discovered Schreiber’s 2010 book Letters from My Grandparents after first reaching her cousin Mindy Ebrahimoff and Mindy’s mother, Jenny Orenstein (née Merel), online. This communication led to Schreiber visiting the town her family once had roots in, and this current artistic tribute to its Jewish legacy.

“We knew nothing about them,” Schreiber said, referring to her grandparents, Samuel and Minna Merel.

Their faces now appear on the first page of the publication below a Hebrew inscription invoking divine vengeance on the heads of those who spilled their blood.

The letters, sent to Lotte, Esther and Nathan, their three children who were sent to the UK when that was still doable, cover what we know of their fate, from Drancy to Auschwitz, where Samuel perished, and to Camp de Rivesaltes, where Minna died. Rivesaltes was used by the French government to transport Jews to the East. Their last spoken words to their children were in Yiddish; they were “Bleib a Yid” [Stay Jewish]. Schreiber’s father refused to set foot in Germany for as long as he lived.

The artwork is not entirely new; it was presented at the Anne Frank Center in New York (2016) as well as the Gershman gallery in Philadelphia (2017). Nor is it the first time Schreiber presents her works in Germany. Her video work “Sheitels,” which deals with the Jewish Orthodox norm that women cover their hair under a wig, was shown at the Jewish Museum Berlin in 2017 as part of the “Cherchez la femme” group exhibition. Yet it is perhaps her most personal exhibition in that country, focusing on her family-related works as part of a Jewish history of loss.

“This,” she said, “has been a way to know my grandparents a little bit.”

Schreiber, who mastered many artistic skills and is a seasoned guide at the Israel Museum, has a rich depth to her artistic oeuvre, which is far beyond biographical.

In Kasher, Kasher, Kasher, shown last year at the Frankfurt Jewish Museum and now in its permanent collection, Schreiber explored the Jewish requirement of women immersing themselves in a mikveh to achieve a status of ritual purity.

These works and others place her at a very interesting juncture. Her art was written about in academic publications as representative of feminist Jewish art of our own times. Writing in 2011, David Sperber argued that Schreiber stands at the meeting point between abjection feminist art and Jewish women-made art today, and noted her courage in removing some very significant scales from our eyes, as in her work Mitzva Night, which brings to the forefront the usually muted aspect of Friday night – that of sexual union between a married Jewish couple.

“Some curators want provocative works,” Schreiber told me. “Most of my work is not provocative.”

WRITING FOR this newspaper in 2007, the late Meir Ronen lauded her skills as a ceramicist, able to create fantastic objects to fool the human eye.

She herself suggests that her various technical skills allow her an insight into the objects on display at the museum, as she is usually aware of how they were made.

When researching her work, I chanced upon a detailed sketch she made of crucifixions based on the ossuary of Yehohanan in the Israel Museum collection. Found in 1968, it is one of the few forensic proofs we have that the Romans really did use this method of execution.

“Chagall also painted crucifixions,” she told me.

Two of his works, White Crucifixion (1938) and The Yellow Crucifixion (1943), are now seen as reactions to persecutions and eventually the destruction of European Jewry during the Holocaust.

She also pointed out that as the ossuary contained physical remains of a Jewish person, what museum visitors see is a replica.

This focus on the body and the eye changes when we consider the mutilated Jewish body during the Holocaust – the hair of Jewish women sheared by the Nazis to be used as stuffing for blankets, the sexual degradation of Jewish women who often found themselves at the mercy of not just the Germans but also non-Jewish males who literally held the power of life and death over them (by offering food or by not turning them in) in occupied Europe. It is likely Jewish men, too, were not above such things.

The subject of the eye is even more powerful. The Holocaust was a very complicated and concealed act of genocide. The Jews who were shot, gassed and burned were not offered an explanation. History books are important, as they offer us mental maps of what happened. When it comes to images, we usually limit ourselves to a few iconic ones. The gates of Auschwitz, German soldiers pointing a rifle at a child in the Warsaw Ghetto, IAF jets flying over Auschwitz as a promise, never again. The result is that we often think we know, but do not look. Our gaze had been fixed for us. When Germans were forced to watch newsreels of what the British and American soldiers found in the camps, they were so terrified they often laughed; others vomited.

DURING A 2017 visit to Sassanfahrt, to visit the Stolpersteine ceremony honoring her grandparents, Schreiber met Anette Schaeffer, who showed her not just that town but also the remains of the mikveh and shul in nearby Hirschhaid.

“At one point,” she said, “Annette turned to me and said: ‘My father was in the SS. I don’t approve.’ It was terrible.”

Schaeffer is co-curator of this exhibition, and Schreiber greatly appreciates her personal courage as well as her willingness to distance herself from the actions of her father, yet this exchange stays with her to this day.

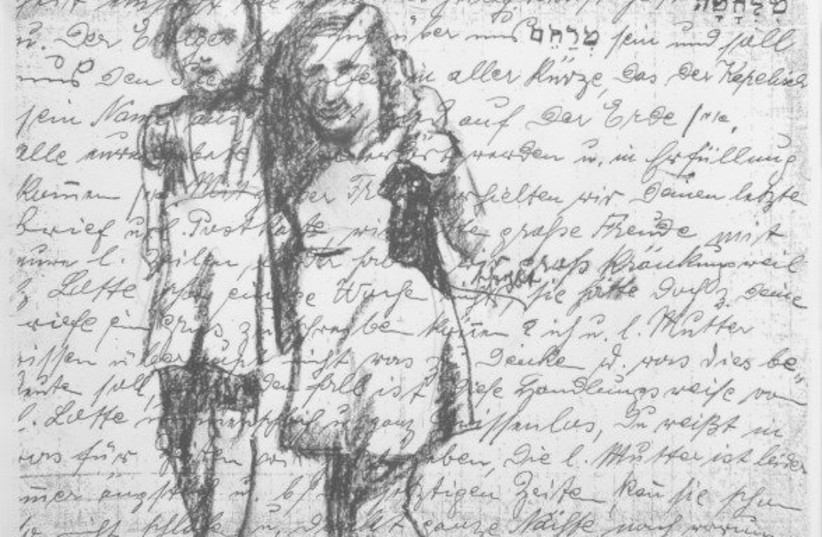

In this exhibition, Schreiber does not follow the example of the allied forces in reeducating the Germans. Many among them, she tells me, seem to have made serious attempts at teshuva (repentance). Instead, she conjures Hebrew letters woven into the original text of the letters alongside her drawings. This almost magical usage of Hebrew infuses them with the deeper paternal need to offer at least some protection to faraway children in a distant land. It reminded me of the discoveries made by archaeologist Yoram Haimi at Sobibor, the personal items the Jewish victims had on their bodies. In prints, mixed media and drawings, Schreiber invokes London as a safe Jewish haven, the faces of the dead, and Auschwitz.

When she began working on these prints in 2012, she invited her father to see them, and he wanted copies. This surprised her.

“I said: ‘Daddy, you don’t want a picture of Auschwitz in your living room,’” she shared with me. “He said: ‘Yes I do; this is my life story.’”

This is not the first time Schreiber creates magical objects. She cast a female bronze figure under the title ‘An Oscar for my daughter, the surrogate’ and in her installation “Against the Evil Eye” a hand grasps a blue eyeball in glass box which would be well placed inside a Wunderkammer. Like Hephaestus, who fashioned objects of beauty to chain the Greek gods when they did wrong, the objects she makes attempt to ratify injustices in her own collected and lucid way.

Seeing as she began her interest in the arts during the heyday of British art historian (and Soviet spy) Anthony Blunt, I allowed myself to ask what she thinks of his idea of cultivating an eye for the arts, an almost intuitive flash of insight into a work of beauty.

“He used to say that there are those who see for themselves,” she reflected, “those who see it when you point it out to them, and those who will never see it.”

“I think it is true,” she smiled.

“Parts of Memory – Sharing Memories. Images of a Jewish Family History” will be shown from November 7 (Sunday) to January 2 (Sunday) at Schloss Sassanfahrt, Schlossplatz 1, D-96114 Hirschaid, Germany. Opening Hours: Sunday, 1 p.m.-5 p.m. Admission: €2 per ticket. The exhibition will continue to Landratsamt Bamberg , Ludwigstraße 25, D-96052 Bamberg, Germany. It will be shown there from January 7 (Friday), 2022, to February 28 (Monday). Open during weekdays, admission is free. Artist’s website: http://www.ruthschreiber.com/shoa