The revolutionary who changed Israel more than Aharon Barak

The truth is that former Supreme Court President Meir Shamgar in many ways started the judicial activist revolution long before Barak.

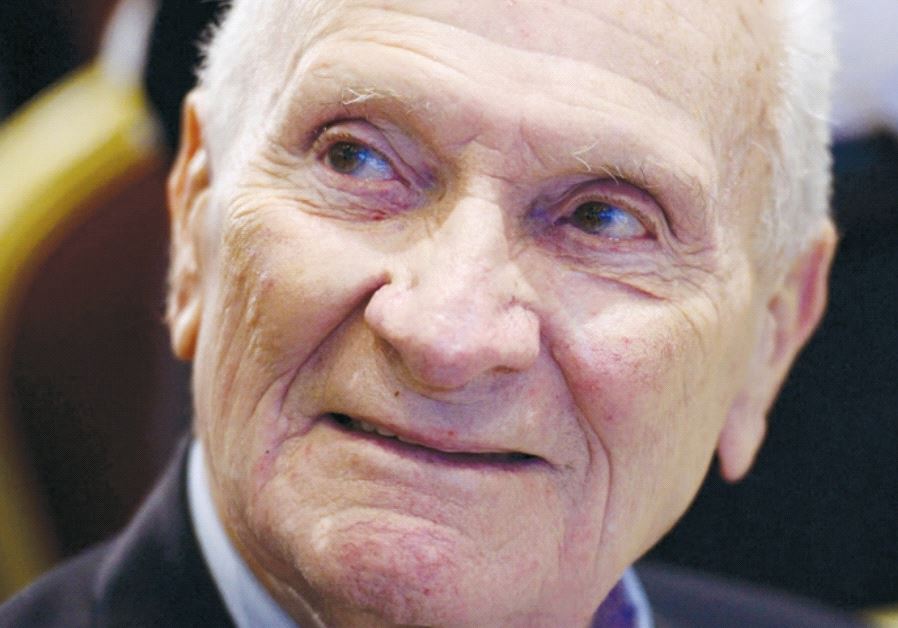

Meir Shamgar, former Supreme Court president(photo credit: KOBI GIDEON/GPO)

Meir Shamgar, former Supreme Court president(photo credit: KOBI GIDEON/GPO)