If you live in Israel, identify with the pronoun “she” and have a good job; if your violent husband has been removed from the house; if you have a position of importance in local government or in the Knesset; or if you just enjoy your life as a woman, you might want to give a little prayer of thanks to Manchester-born Frances Raday.

The aliyah story that impacted women’s rights and human rights in Israel began shortly after the Six Day War. June 1967 found Raday in Tanzania, lecturing at the newly established Law Faculty in Dar es Salaam. The war turned much of Africa against the victors – Israel’s consul in Zanzibar, Uri Raday, was forced to flee to Dar, where Raday, too, was feeling the backlash and had decided to spend time in Israel. They met in Africa and married in Israel soon after.

The elegant young lawyer hit the holy ground running: she studied Hebrew, did a doctorate, and passed the foreign lawyers exam while tending to her growing family of three kids. Then, in 1975, a young married secretary at a Jerusalem yeshiva reached Raday’s office. The yeshiva’s head of education, she complained, had repeatedly harassed her by leaning over her desk and breathing heavily in her ear; his inappropriate stream of innuendos was driving her nuts. When she complained, the yeshiva fired her.

Raday took the case to the Labor Court and won severance pay; the yeshiva closed down as a result, although the abusive educational director retired with a full pension. Raday was on a roll. As her academic career blossomed (she became a full professor at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, as well as director of the Concord Center for Integrating International Law in Israel), she simultaneously became an acclaimed human rights litigator. Her next big case was at Hadassah hospital where female professors and heads of departments were forced to retire early, at 60.

When Raday faced failure in the Regional Labor Court on raising the age of women’s right to work until 65, as it was for men, she changed tack. In 1984 she met two of the biggest names in the feminist movement: Betty Friedan and Elizabeth Holtzman. Friedan’s The Feminist Mystique rocked the West with its expose of desperate housewives in the 1950s: women with loving husbands, lovely children and heavenly suburban houses. “I have it all,” these wife/mothers wept, one after another. “And yet I’m so miserable I want to die.”

Friedan diagnosed “the problem with no name” as something that should not be treated with valium, or medical advice to “have another baby.”

She concluded that women should get dressed, get out of the house, get a job. And so began the famous female trek back into the workplace. Lawyer and US Representative Holtzman was equally instrumental in fighting for equality and justice for women; and in 1984 they were both invited to Jerusalem for the first Israeli conference on women’s rights.

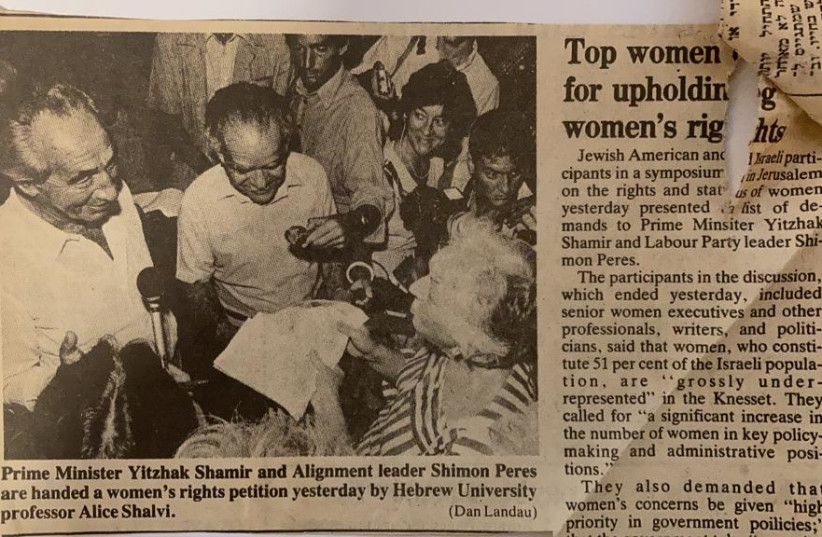

The conference was a phenomenal success, with the establishment of the Israel Women’s Network with Professor Alice Shalvi as its head. Raday collaborated with Holtzman on a draft manifesto setting out demands of women in the Holy Land.

Fortuitously, around the corner from the conference venue, Shimon Peres and Yitzhak Shamir were holed up in the King David Hotel, hammering out a manifesto of their own: a national unity government. Delegates from the conference braved bodyguards in the gorgeous grounds of the iconic hotel, and to general astonishment, the two gentlemen of Jerusalem strolled outside to accept the manifesto.

Years later Hadassah heads of departments were facing being forced into the kitchen as they hit the big six-oh. An august Regional Labor Court judge dismissed Raday’s appeal for equal retirement age for all in legendary fashion: because husbands are usually older than their wives, he proclaimed, if they retire first working wives will order them to “do the laundry, motek (honey), and feed the cat.” That would never fly.

Raday approached Friedan and Holtzman, who contacted Hadassah’s American leader, Ruth Popkin, who was not forthcoming until she heard that The New York Times was waiting to headline how Israeli women would have to hang up their scalpels and bake bread for their older working men.

Raday recalls that Popkin immediately ordered Hadassah to sign a collective agreement allowing women to keep their jobs.

Raday eventually took the issue to the Supreme Court, which ruled that women may choose to retire earlier than men but cannot be forced to do so. Ironically today, Finance Minister Avigdor Lieberman wants to raise the minimum retirement age of women, to save on pension payments.

In Israel, where buying an ice cream has political implications, gender issues can make women’s hair rise, whether it’s covered with a wig, scarf, hijab or blowing in the breeze.

When marriage and divorce are dictated by religious law, and the Women of the Wall – despite a long saga of litigation in the Supreme Court where Raday represented them – are still not allowed to pray in their way at the Wall, lawyers like Raday can feel pretty desperate.

“We’re still fighting for religious parties to allocate Knesset seats for women,” she says, “and progress on this and other problems is slow. But we cannot give up.”

Raday has served as an expert member of CEDAW – a UN Convention for the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women – where she advocated for extending to all countries the prohibition of marital rape, decriminalization of adultery, and the right to abortion.

She’s the only Israeli to have served as a special rapporteur for the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, where she chaired the working group on Discrimination against Women. Forty-seven members sit in rotation on the Human Rights Council; only seven are from Western countries. When delegates from Saudi Arabia and Iran are passing resolutions about veils, polygamy, and women’s rights to equality in the family, she reminisces, things can become quite Kafkaesque.

Raday, who has dedicated her life to human rights, recently addressed Amnesty International’s claim that Israel is an apartheid state.

“Apartheid is the control of another people with an intention to retain racial control over them,” she explains. According to her, Israel still has some intention to separate from the West Bank and abrogate control; Israeli presence is linked with defensive occupation. But she worries that a settlement policy of creeping annexation, which could result in formal annexation, could tip us past the point of return.

“We’re on a razor’s edge,” she says.

Still, she argues, Amnesty’s claim that pre-1967 Israel is an apartheid state is just a falsehood: AI aims to make Israel one of three pariah states in the world, the others being apartheid South Africa and Myanmar. That would result in excluding Israel from the UN, and turning the country into a giant ghetto as Israelis would risk prosecution abroad on the grounds of contributing to apartheid.

Raday is still fighting the good fight, and remains optimistic. “We have to overcome the ethnocentric, religious, messianic fanaticism on both sides of the conflict here to deal with the real challenges of humans: living a decent life in a challenging world of climate change, pandemics, increasing rarity of natural resources, and population explosion,” she insists.

And she doesn’t plan on retiring any time soon. ■