“I’m part of a great movement throughout the Arab world,” says veteran Arab-Israeli journalist Nazir Magally. “You don’t hear about it because it’s not organized into political parties. Israelis don’t hear about it because they make no effort to listen. Some don’t want to listen, but Israel is feeling these changes – the Abraham Accords are bringing it home.”

He is referring to updated evaluations of reality percolating throughout the Arab world, and especially among Arab citizens of Israel.

“This initiative is primarily aimed at the Arab public in Israel,” reads the foreword of The Responsibility of the Minority. “Its source is a sober view of the tremendous potential inherent in the important role of Arab citizens as a national minority in the State of Israel.”

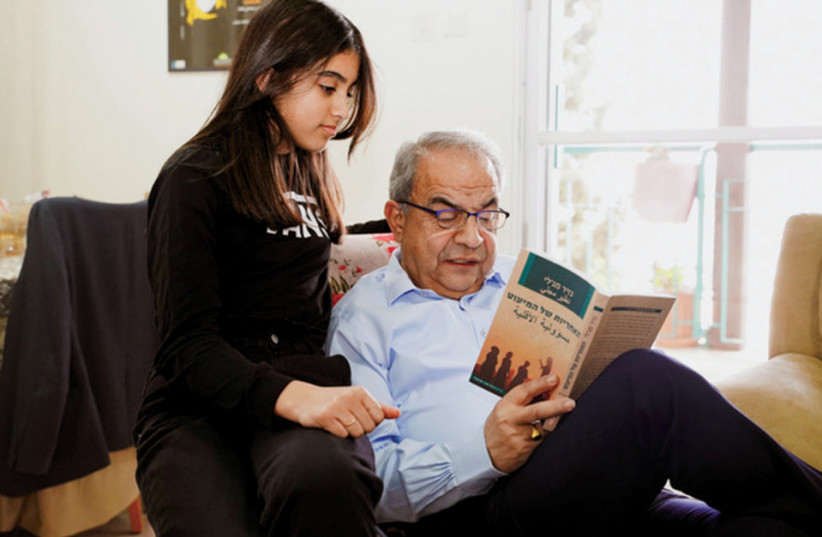

Magally’s sixth book was published last month in a bilingual version by Yediot Aharonot Books, in conjunction with the Shaharit think tank and the Penima movement. It is part of their new series Beit HaYotzrim, aimed at articulating a political agenda that can break out of the dichotomies that define Israeli society today.

As a minority, Arab citizens of Israel have always been viewed with suspicion by the authorities, Magally explains in the book. Successive Israeli governments have treated Israeli Arabs as an internal enemy instead of forging a combined reality. One reason for the failure of the Oslo process was Rabin’s reluctance to involve Israeli Arabs in the negotiations, he claims.

Both Israel and the Arabs have lost out by not recognizing this potential. “We should serve as a bridge and model for coexistence,” Magally writes in the book. “No Arabs know Israel better than we do, and no Israelis know the Arab world better than us.”

Without appearing to play the blame game, Magally analyzes where Israeli Arabs have gone wrong. “We developed a reactive mentality instead of a proactive one,” he writes in the book. “We demand the democratic rights due to us in Israel, which is justified and important, but we ourselves, as a society, are still far from democratic.”

In an interview in his Nazareth apartment, Magally tells the Jerusalem Report: “The Israel-Palestinian conflict must be put behind us so we can look after ourselves. It’s our responsibility. We have tremendous potential to positively influence the conflict, but instead of using our special status, we’re missing out.”

Magally does not hold back in presenting the reality as he sees it.

“There’s a racist policy in Israel against the Arabs – but much of this is because of our local authorities,” he says. “Clans have taken over, so many of us don’t pay full arnona (property taxes), corruption is rife, and the local authorities are either too corrupt or too scared to address local issues. We have to fix ourselves.”

This, he notes, can be said about anywhere in the world.

“The minority has to solve its own problems in order to become part of general society,” he insists. “The time has come to stop being the poor minority. If we don’t do this correctly, it will perpetuate the conflict.

“The West is wrong when it tries to force its values, such as democracy, on others. Because something works in Finland doesn’t mean it’ll work in Egypt. Likewise, what works in Rishon Lezion won’t necessarily work in Sakhnin. Untold many have died because of this mistake.

“We have to find a way to allow people to be within their space, and to decide how close they want to approach the West. Be humble. We have many values that can help the West fix itself – like family, self-sacrifice, honor and tradition.”

Magally tells his personal story. “My father was a Bedouin policeman for the Mandatory government. In May 1948 he ran away to Jordan from Beisan [now Beit She’an] with his young family and clan. Two months later he escaped back to the village, then returned to Jordan to bring the family, only to be arrested by Jordanian police after criticizing the Jordanian royal family during a political argument in a café. He escaped [Jordanian] prison and found his way back to Beit She’an, only to find Jews occupying his home. He even offered to buy back the house, but was told by the fledgling Jewish authorities ‘to accept the new reality’ as a refugee. My three half-sisters were forced to remain in Jordan with their grandparents. Two of them live in a rancid refugee camp to this day.

“My father rented a tiny two-room rooftop apartment in eastern Nazareth, found work as a tracker for the Israeli police and had more children – but could never forget the humiliation of being a refugee, and died young at 54.”

Nazir was the first of nine offspring born in the then-predominantly Christian city. “I was a minority from the outset – a foreigner from a refugee family, a Muslim in a Christian school [the renowned Terra Santa school]. A minority within a minority within a minority.”

Growing up in this environment sharpened his desire to improve the reality around him. “I knew I wanted to be a journalist from a young age,” he says.

Magally started as a reporter for the only independent Arabic daily at the time, Al-Ittihad (The Union) run by Rakah [the New Communist List], under its legendary editor Emile Habibi. He stayed for 27 years, rising to editor-in-chief for seven years only to be fired in 1999 after publishing an article critical of the party’s leadership. “I couldn’t be obedient,” he shrugs.

Nowadays, Magally is an in-demand freelancer. He presented a weekly Arabic current affairs magazine on Israeli television, commentates on Israeli affairs for the London-based Al-Sharq al-Awsat newspaper and the Al-Arabiya network, and is quoted regularly in the Arab media on Israel and the Hebrew media on Arab affairs.

He is also a founder and senior fellow at the Shaharit think tank and nonprofit organization, headed by Dr. Eilon Schwartz, which strives to “forge a new social partnership between all segments of Israeli society.”

“I foresee a calm struggle – that’s part of my political thinking. I’m not in favor of a military coup to overthrow any Arab leader. In the Arab world, kingdoms are overthrown only to be replaced by nationalists who establish corrupt regimes lacking content. This has brought down Arab culture, which used to lead the world – we once stood at the top of the pyramid of human society. The Arab world wasn’t born in the Third World, although it’s there now.”

In May 2003, together with the Catholic priest Emil Shoufani, Magally led a delegation of Arab and Jewish public figures to Auschwitz, one of two visits to the site.

“Understanding our Jewish neighbors is part of our responsibility,” he says. “We’re the only ones who can see both sides – and the price of the conflict for both sides. In the Second Lebanon War, 19 Arabs were killed by Hezbollah rockets, while our relatives in Lebanon were also getting hit by the IDF.

“When there’s a terror attack, we know to feel the pain of both sides. My wife and I watched Jewish women crying at funerals last week [in early April] and we cried with them. We also feel the pain of the Palestinian mothers who lost their sons. In Ramallah I tell them of the pain of Jewish mothers. No other Arabs do that.

“Just like you, I also question what turned a brilliant computer expert into a terrorist – and we have the courage to answer such questions. But the guys who left Umm el-Fahm and Rahat are harming this coexistence and destroying trust. The Arab policeman who shot the terrorists, the doctors who treated the wounded and the cleaning workers who washed away the blood are rebuilding this trust.

“Some say we’re torn between our country and our people, but I don’t agree. If we put an end to the conflict we’ll benefit doubly – as Israelis and as Arabs. We should see ourselves as an example to the rest of the Arab world.”

So why is your influence not felt?

“We have a problem with our leadership, which doesn’t seem ready to take responsibility – neither does the Arab media. Our political leadership puts blame on the government or police instead of looking inward and solving the problems within our society. Violence has become such a part of our culture; blaming others shows that you’re not a real leader. It’s our responsibility to look after our daily life in Arab villages.

“I’m not coming to change the leadership, but rather to influence it. This should be the role of the media, but nowadays there’s a plethora of websites and publications but no investigative journalism, and most [news outlets] are linked to a party.”

A modest man, the 69-year-old Magally lives with his wife, Ibtehad, a consultant on women’s advancement for the Nazareth municipality. They have two daughters – a school principle and a senior Arabic educator in Afula and Nof Hagalil – and a businessman son, and six grandchildren.

Everything in his demeanor exudes humbleness. “Just like the Jews, almost all of us want to live in peace,” he sighs. “If we seek it, we can find a common way. That’s the only way.”

Timing, it seems, is not Magally’s greatest ally. The Responsibility of the Minority was released just after Russia invaded Ukraine, and just before a spate of bloody terror attacks threatens an already delicate coexistence. “It’s too early to talk about reactions to the book,” he says. “I don’t believe this book will create a revolution. I just want to do my bit to contribute.” ■