Late summer 1967, while a volunteer from abroad working for Israel in the Sinai, representatives of the IDF and WZO asked me to help form and then lead another group of volunteers from abroad for tasks on the Golan Heights. Our base there would be just south of the recently deserted town of Quneitra, which was abandoned by the Syrian army during its retreat from the Golan in the June fighting. That base was a half-mile or so from the new frontier with Syria.

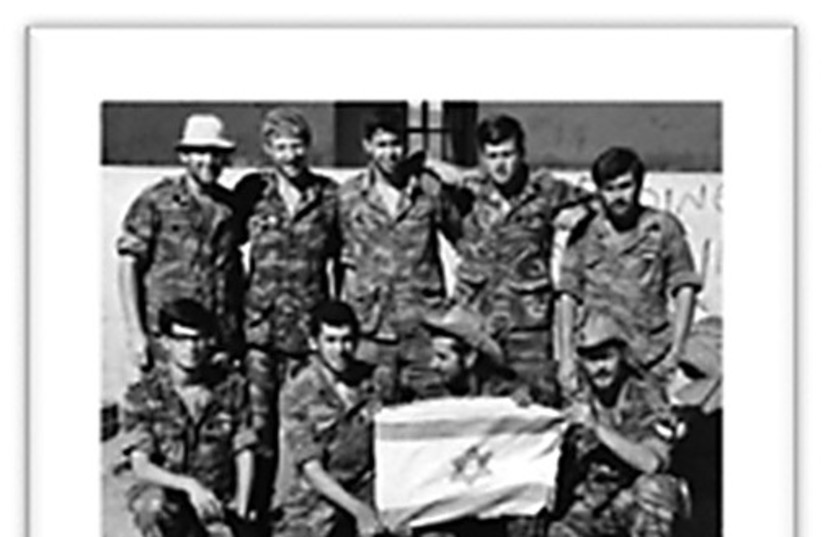

This group was comprised of all men, recent volunteers to Israel from English-speaking lands (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, UK, USA). Most had already worked elsewhere for a month or two in Israel or the new territories, and so were relatively veteran volunteers.

Our volunteer group in the Golan Heights collected vast amounts of assorted abandoned Syrian military equipment from the heavy fighting in the area. Tanks, armored personnel carriers, trucks, artillery pieces, mortars, small arms – some thousands of pieces of armament. We moved the gear to military bases in northern Israel. The task took two months.

On the Golan Heights during the late summer of 1967, a captured, undamaged, Syrian T-34 tank is loaded aboard a flat-bed trailer for transport to an IDF base in the Galilee. The Soviet-built armored vehicle was famous in military circles for dependable, effective service against the Germans on the eastern front during World War II.

A flashback to one enjoyable event: some fellows spotted a sheep wandering around wild in a field near our base and corralled it. We had been sharing meals at the local army mess hall, dining with men of a Golani infantry company stationed on the heights just south of Quneitra, along the new demarcation with Syria. The chow was quite poor, and having spotted the potential lamb roasts, we volunteer leaders immediately thought to arrange a barbecue feast. Soon enough we carried that out to everyone’s pleasure, even butchering the critter kosher-style (so the Orthodox among us could partake) under the direction of a religious fellow in our group who had volunteered from Brooklyn.

A large contingent of volunteers also worked cleaning up Mount Scopus, the just-liberated former campus of Hebrew University in eastern Jerusalem. It had been unused for its original purpose for 19 years, since 1948, when Transjordanian forces captured the area. The Kingdom of Transjordan had then annexed territory it gained west of the Jordan River, including much of Jerusalem, and renamed itself the Kingdom of Jordan, i.e., flanking both sides of the famous river.

Transjordan, which is eastern Palestine as per the League of Nations Mandate of 1922, was ruled since World War I by the Hashemite tribe and dynasty, some of whom had assisted the British during that conflict, working with Colonel T.E. Lawrence, later nicknamed “Lawrence of Arabia.”

The Hashemites had migrated north to the Palestine region from Arabia toward the end of and after WWI, after entering, fighting, and losing a civil war in the Arabian peninsula with the Saudi tribe, and became rulers, courtesy of the Brits, of eastern Palestine. This area was renamed Transjordan for its location relative to cis-Jordan (i.e., western Palestine) across the famous river, and the heartland of Eretz Yisrael. This may sound like a complex history, but it is simple when you grasp the outline and framework of the geography.

In 1948, during the first Arab war against modern Israel, the Kingdom of Transjordan captured territory of western Palestine, i.e., west of the Jordan River. This western portion is brimming with sites mentioned in the Bible, particularly the area soon popularly called the “West Bank” since it was west of the famous river running north to south into the Dead Sea.

The Galilee is north of what is called the West Bank, or Judea and Samaria, and the Negev region is southward, also west of the lowland running south from the Dead Seat to the Gulf of Eilat (called Gulf of Aqaba by the Arabs) connecting with the Red Sea. It is simple once you understand the outline and complexities!

I gathered there were additional volunteers working elsewhere in the environs of Jerusalem, especially to its north, and at Israeli agricultural communities – kibbutzim and moshavim – and at factories and other facilities across the country.

Eilat

Before the 1967 war, Israelis considered Eilat, Israel’s most southern community, the far frontier, “the end of the world.” By autumn of that year, this small city became a midpoint on hastily printed new maps that included pre-war Israel plus all Sinai, Gaza, Golan, Judea and Samaria. New areas were marked with nomenclature according to political sensitivity and orientation of the cartographer or publisher: as part of Israel, using either the term “Liberated,” the designation “Conquered,” or the neutral term “Administered Areas” then favored by Israel’s Foreign Ministry. Sometimes the geographic terms “Gaza,” “Judea-Samaria” or “West Bank” would be used.

Eilat, the jump-off town from Israel to southern Sinai became a place to relax for volunteers who had come to Israel from around the world when the war broke out. There, some of us in the autumn of ’67 rested and caught up emotionally, beginning to digest and make sense of our adventure in history. We all understood that is what it was.

I spent more than a month around Eilat that autumn. The town’s youth hostel on a bluff overlooking the harbor, and a Sinai beach on the other side of the old frontier with Egypt, were homes to me and some volunteer buddies. The weather was fine. Volunteers and tourists seemed caricatures of their home country stereotype, or so we projected. New friends called each other by slang terms – Yank, Aussie, Limey, Frog, Canuck – and acted to fill those roles.

We were light-hearted and happy. Everyone laughed a lot. There were arm-wrestling contests at the hostel on the dunes. And we encountered a new Israeli sandwich treat, notably bread slathered with chocolate spread. We sampled food at all the street kiosks, finding the best for falafel, hummus, and eggplant salad, and frequented a local inexpensive restaurant, where we drank beer, nibbled olives and pickles, and feasted on turkey schnitzel, fries, and cucumber-tomato salad.

On the hottest days when not working, we often shopped carefully – i.e., slowly – in the air-conditioned supermarket to enjoy and appreciate the cooled atmosphere. Our youth hostel did provide hot showers. Frequently we camped on Coral Beach, beyond the old Israel-Egypt border a mile or so into Sinai, where we built lean-tos of wooden planks and flattened corrugated cardboard boxes to provide shade as protection against the midday scorching sun.

For bread and a pastime, a few buddies and I worked for a month or so at Timna Copper Mines, in the hills a dozen or so miles north of Eilat. Our job was to carry tools, heavy shoring, and cases of dynamite from the surface down deep into the mine shafts. Tough hourly labor, hard-hats and all, where King Solomon’s mines once had flourished. We gathered that in biblical times, ships plied Jewish copper ore and wares from this area through the gulf (from the neighborhood of today’s Eilat and Aqaba seaports) to the main body of the Red Sea and onward to coastal regions of lands now called Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Sudan, Eritrea, Djibouti, Somalia.

During our days in Eilat, my Aussie buddy Barry M. hit it off with Margie, a volunteer from New York. After journeying homeward, their romance flourished despite the distance. They later married and have since lived Down Under (i.e., in Australia). Barry and I stay in touch by telephone and now also by email. We even have done business together: he distributed in Australia the computer products produced by an American company for which I worked some years as marketing director. Sometimes we are awed by how we met in Israel following the dramatic 1967 war, and by the durability of our long-distance friendship, now more than half a century.

“I knew you when we hauled explosives for a living, and often spent evenings and nights relaxing under the stars on the Sinai beach,” Barry reminds me from time to time.

“I knew you when we hauled explosives for a living, and often spent evenings and nights relaxing under the stars on the Sinai beach.”

Barry M.

I had slept without dreams, viewing in daylight the mountains tan and pink across the sea in Arabia – hazy and mysterious, but not beckoning. We were at home, a home to our ancestral families long before the places of our births, profoundly happy to be in this land of our heritage, aware that volunteering meant something profound, undefined but life-changing. Our ancestors came from this land, nearly two millennia ago. The ancient homeland and culture beckoned at a time of need, and we had responded and returned. ■

Michael Zimmerman is an American who went to Israel as a volunteer upon the outbreak of the 1967 war. He lived there for some years in both the Tel Aviv and Jerusalem areas and worked in various jobs of interest and helping out the society’s renaissance. He has several university degrees, taught courses in international relations and strategic affairs, and contributes stories to The Jerusalem Report.