ON October 25, we had reached the 13th day of a two-week visit to the US, which had been well planned by my son Avie. Not only had we been able to participate in two major events in Atlanta, Georgia, and Scranton, Pennsylvania, but we also had quality time with very close relatives whom we had not seen for 17 years. We were now in New York, our final stop, getting ready to fly back to Israel, our home for 45 years. Before we left, I decided to find out what Americans, between 76th and 74th streets on Broadway, knew about Israel. I had heard little or nothing on TV about Israel except for three minutes on the elections, featuring Bibi Netanyahu’s picture and a projection of his Likud party’s victory.

Sitting in McDonald’s drinking coffee, I asked three young people in their 20s, “What is Israel?” None of them knew, though one suggested it might be a “fish.” I walked outside and asked the gentleman at the newsstand where I bought my paper. He said, “I do not answer questions.” Next, I walked over to a delightful young man whose display of multicolored flowers were waiting to be purchased. He asked me to repeat the word “Israel” a few times, but said he was sorry he could not help.

A little frustrated, I asked three or four people passing on Broadway. One older woman said that she had heard the word but did not remember what it meant. Two other men were not helpful, either. I saw a Chinese woman in her 20s and I asked her. When I said “Israel,” she immediately answered, “That is where there is a continuing problem with Palestinians.”

“Israel. That is where there is a continuing problem with Palestinians.”

A Chinese woman

Now I was about to experience an unexpected conclusion to my survey. First, one man said to me harshly, “You have no right to ask me any questions.” Two or three others in their 50s did not have any answers.

I was ready to give up, but when I reached the next corner, there was a very impressive bank. I walked in. A well-dressed man stood behind a large glassed-in entrance area. He asked if he could help me. I said, “Can I ask you a question: What is Israel?”

“I know everything about Israel,” he said.

“Why?” I asked.

“Because I am Jewish,” he replied.

I could have hugged him, but I just shook his hand.

In mid-October, we had flown from Israel into Orlando, Florida, where my late wife Rita’s brother and his family live. He and his wife retired there after 40 years with the American government to be near their son and his family. My birthplace is Georgia, but Florida was the place to visit when I was in college. I attended Emory University in Atlanta and traveled with my fraternity brothers down to their homes in Jacksonville, Daytona Beach, Orlando, West Palm Beach, Miami. Back in the 1950s, there were a lot of orange trees and other vegetation. Now with Disney, Universal Studios and Racetracks, Florida is quite different and is one of the main states where Jews retire. Some 700,000 live in Florida, a major political entity.

In 1958, on a visit to West Palm Beach with my fraternity brother, I felt the sting of antisemitism for the first time. Driving around on a Saturday night, we reached a main crossroads to enter Palm Beach. The police stopped us. Shining their flashlights on our faces, their words exploded.

“You have two strikes against you,” one trooper said emphatically. “Not just anybody can drive into Palm Beach – you must show an invite. So, you better get going, Jew boys, before I arrest you for blocking the road.”

My brother-in-law and his wife, close to his son and family, have homes just outside Orlando. My nephew and his wife have been successful in film and publishing, so they have a lovely home with a pool, sauna and other additions. I thought we had seen their whole house. Before we went to my brother-in-law’s home to sleep, my nephew took us downstairs to his movie theater with some 25 seats, where they show movies of many vintages.

I had heard that my wife’s brother and his wife live in a gated community. To me, that meant small houses. However, I was mistaken. Their home had many rooms, all on one floor, and a beautiful swimming pool for which you can adjust the temperature. The post office will not deliver their mail because out of the 40 houses in their community, only a few have permanent residents.

Then, unexpectedly, we discussed a new American Jewish phenomenon. Their community is about 25 minutes away from Disney, United Studios, and other noted parks. Haredim and Orthodox Jews rent the empty houses in the development. They have a lot of children. For example, in one house, we were told, there had been a family of 10 for one of the weeks in the winter when schools were on vacation. If they want to have a synagogue, be it Chabad or some other type of Orthodox stream, they must rent a house closer to Orlando, which is more expensive. Most of these northern visitors send their food from New York in a refrigerated truck for the time they will be vacationing.

From there, it was on to Barrier Island, about 15 kilometers south of Sarasota on the Gulf of Mexico, the west coast of Florida. My nephew and niece have an exquisite home on the island where the fury of the hurricane hit. Their home was spared. Some of the other 50 homes were damaged severely. The writer Stephen King lives there, and he has put up little visual treats around the island deriving from his books. Not too far up the highway, north of Sarasota, is another gated community, somewhat more expensive. People first moved there about 25 years ago. Unlike communities of this nature on the east coast of Florida, filled with Jews from the northeastern part of the US and Canada, there is a mixture of Christians and Jews.

Living there, probably unbeknown to most homeowners, is a couple, Dee and Arnold Kaplan, whom scholars acclaim as among the most outstanding Judaica collectors in the US today. How do I know them?

When I was a rabbi in Scranton in the last decade of the 1990s and a few years thereafter, Arnold Kaplan called me from Allentown, Pennsylvania, and invited me down to see some of their collection of American Judaica. When I entered their home, he asked me to sit down. He brought out a large bound volume of Philadelphia newspapers from the 1770s. He opened one page of ads, and there was one Haym Salomon. Then more pages with the name of that noted individual again, and more ads of Jews, such as Benjamin Nones.

The Kaplans showed me around their home to see more and more paintings of Jews from the 19th century, Torah covers, Passover plates, matzah covers and hallah covers and a Pennsylvania Dutch birth certificate signed in Yiddish. The piece de resistance for me were 4,000 illustrated trade cards from every state in the US, vintage 19th century. Trade cards then were art forms compared to our sterile business cards now. Instantly I became a “groupie” of the Kaplans. We met several times in 2003. Then they moved to Florida, and we returned to our children and grandchildren in Israel.

The locale selected for their mammoth collection is the archives of the Judaica library of the University of Pennsylvania, headed by Arthur Kiron. The Kaplans have donated 13,000 American Judaica items of all types from 1550 to 1886. On our visit, my son, my brother-in-law, and my nephew witnessed Arnold showing us new items he had collected. He loaned an image for this article. God should give the Kaplans strength to continue.

On to Atlanta, where a special event was held at the Stuart A. Rose Archives at the Woodruff Library of Emory University. Six Geffens of Atlanta – children of my grandparents Rav Tuvia and Sara Hene Geffen – attended Emory University beginning in 1919 through the latter part of the 1930s. I was fortunate to be there in the 1950s.

In 1919, my uncle and another young man were the first Jews to attend Emory after Rav Tuvia Geffen negotiated a compromise with Bishop Warren Candler, president of Emory. Since attendance at Saturday classes was mandatory, my uncle and his friend walked four miles to Emory and back. They were in class, but they were not required to take notes or tests – no writing.

Twenty-five years ago, my parents, Anna and Louis Geffen, had donated their papers, scrapbooks, objects to the Rose Archives. I decided to set up a small fund in their names. There were no solicitations, so the fund grew from friendly contributions. In 2019, my cousin Marc Lewyn called me in Israel. His father, Bert Lewyn, survived in Berlin. His great-uncle and aunt, my grandparents, sponsored him in 1949 to move from a DP camp to Atlanta. Marc told me over the phone that he and his family had decided to contribute the necessary funds to be added to what I had collected to create the Geffen and Lewyn Fund. Working with the director of the Rose Archives, Jennifer Gunter King, our contributions became the fund for the study of southern Jewish history.

At an event on October 19, the president of Emory, Gregory Fenves, the first Jewish president of Emory and son of Holocaust survivors, told the story of my grandfather and Emory, and then dedicated the fund.

I became emotional when I spoke and forgot most of my speech, but those present said I had succeeded in getting my message across. Marc spoke and showed the fifth book in German which included the story of his father, who, for over two years, had been on the run in Nazi Berlin. At this exciting moment in my life, I was very proud that my oldest son, Avie, was present. My son knew my parents, Anna and Louis Geffen, well. In addition, he knew my late wife Rita’s parents, Frieda and David Feld, too. Before my wife died, she gave him all of the archival material and photos of her parents to scan. When we made aliyah, she brought them all to Israel because she wanted to hold on to them. I believe what she left is larger than my parents’ archives. Ultimately, it will be at the Rose Archives, too.

There were about 100 people attending the Emory event. Marc Lewyn and I were happy; we had worked several years shaping the fund into what we wanted it to achieve in the years to come.

I shared with the audience one exciting story about Emory, which only one other person present knew. Sitting in the audience at the dedication on October 19 was an Emory alumna, Lois Frank of Atlanta, who smiled at me. Her husband, Larry Frank, an All-American at Vanderbilt University, was our football hero when I was a youngster.

In 1962, as a student at Emory, Lois was in the organization bringing speakers to the campus. She invited Dr. Martin Luther King, whom a family member knew. He accepted. She made arrangements for a room for 50 people in the Alumni Memorial building, where he would speak. She picked up Dr. King and his wife, Coretta, in her Volkswagen Beetle and brought them to Emory.

On the campus, interest in him grew, even before his monumental civil rights acts efforts, so the students came. Even some individuals outside the campus were permitted to attend. By the time MLK was to speak, at least 1,500 people were present, so he spoke outside. There were no riots. But no pictures, no announcement to the press or TV or radio. Eight days later, in the student newspaper The Wheel, an article about the MLK happening was published. Lois Frank and I, on this October 19, smiled at each other. Those people present learned what happened at Emory – the president, too.

While in Atlanta, my birthplace, I was walking around the original quadrangle of Emory University. I saw signs announcing it was Tibet Week on the campus. I asked an Emory student about it, and he explained that there are now a small number of Tibetan students at the university. Naturally, this question popped into my mind: “Is there an Israel Week?”

“I think before I was a student here, there was an Israel Week,” he replied. “However, the campus became too tense. The campus police could not handle it, and the administration decided to stop it.”

Since the shooting at the synagogue in Pittsburgh with 11 murdered, the president of Temple Israel in Scranton, where I spoke, arranged for police, paid privately, 24 hours a day. I knew about it because the president had mentioned it when we were corresponding about my visit. Since I had been friendly with some of the staff at the local newspaper, I asked if there would be a story describing my upcoming visit.

“Rabbi, we never put an advance story in the paper of any event,” I was told. “We fear what might happen, so the event is described after it has been held.”

On to Scranton, once the “King of the Coal Country,” where I served as a rabbi at Temple Israel, the Conservative synagogue there. Parshat Beresheet, 2022-5783, the congregation celebrated its centennial, and I had been invited to be the guest speaker. I was the rabbi there in 1996 for the 75th anniversary, and we hosted documentary filmmaker Mark Harris, an alumnus, who has won three Oscars. He was also awarded an honorary doctorate by the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. A time capsule was planted then and was opened up for the 100th when a new time capsule was planted.

The spirit of Bill Clinton was present at Temple Israel, and the daughter of family who had the connection was present. Hillary Clinton’s father, Hugh Rodham, grew up just outside of Scranton. His best friend, Manny Gelb, was a noted amateur boxer in his youth. Hugh always told the story “When Dorothy and I went to a dance, Manny would whirl my wife around the room.”

In fact, when I arrived on January 1, 1993, Manny and his wife, Miriam, had received an invitation to the inaugural luncheon to sit with the Rodhams. When the Gelbs returned to Scranton, we all received a complete run-down of the event, including the famous people and the Gelbs. The centennial was a lot of fun as such a celebration should be. I opened by saying I was invited so I could celebrate the 100th birthday of Millie Weinberg, four generations of her family in the synagogue. She was thrilled when we sang “Happy Birthday.”

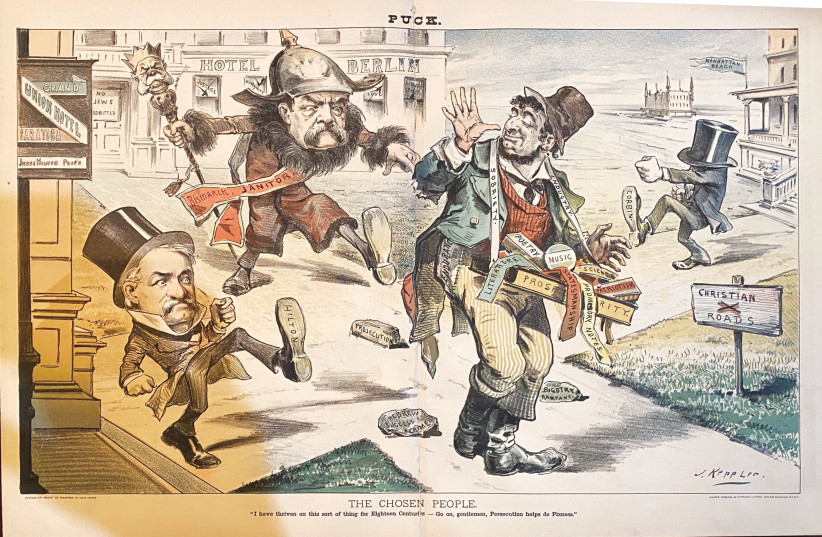

The first rabbi of Temple Israel was Dr. Max Arzt, who left the synagogue in the late 1930s and became the vice-chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary. One of Arzt’s converts was a gentleman, T. J. Connor, who during the depression years began to draw images for the cover of the weekly bulletin, The Messenger. He presented interpretations of the parashot and holidays in folk art. Most famous is his cover on Hitler and the SS. In 1936, Arzt gave Connor information about the Nazis when he returned from the World Zionist Congress in Europe. The cover offers an artistic statement about the hoped-for fall of Hitler.

I respect the members of Temple Israel, now especially the president, David Hollander, because they are dealing with a dwindling population. There are few Conservative or Reform Jews moving into Scranton.

The Temple Israel leadership works hard to maintain its Hebrew school with very few students. Cantor Vladmir Aranzon has been there for 23 years. I helped him, his wife, and children receive a visa to go to America from the Soviet Union. I had first heard him sing when he was in the US performing with a cantors’ choir from the Soviet Union. He and his wife, a certified physician’s assistant, have lived a most enjoyable life in Scranton for over two decades.

You cannot imagine what joy I felt to be with the synagogue for its centennial. The sad part for me was to remember such wonderful people and committed Jews who have died. The congregants were telling me constantly how they missed Rita z’l because she was a very special woman. Her charm and grace, her intellect, her work with the Russian refugees who came to Scranton was unique because of her fluency in English, Russian and Hebrew.

I found those members, whom we knew well and who were alive, were fanatically dedicated to the synagogue. It is theirs, and they never want to let it go. I understand them completely because Temple Israel is a synagogue whose history is filled with outstanding Jewish education, amazing Jewish Boy Scouting in a different era, and a multitude of American patriots who fought in World War II. Most of all, for over 60 years Temple Israel has a daily minyan morning and evening. During corona, there were Zoom minyanim every day. Now Temple Israel members attend in person. Certainly, it is harder to keep it up, but members are assigned days when they attend. This is the essence of committed Conservative Judaism.

However, Jews are moving into Scranton. Thirty years ago, the famous Lakewood New Jersey Yeshiva opened a branch in Scranton. On Shabbat morning, when my son and I came out of the synagogue, walking on the other side of the street were men in streimels, big black hats, children with payot. The yeshiva has done well. People move to Scranton because the housing is less expensive. There is a very fine haredi day school. The yeshiva has two levels for different ages. Judaism will not die in Scranton.

We drove to New York for a day and a half more. We spent time with my cousin Prof. Barbara Birshtein, who taught at the Albert Einstein Medical School. We also met her grandchildren. After that, my son suggested we go to Ground Zero, the site of 9/11. Arriving there, my son had to explain it to me: There is a reflecting pool; there are the names around the pool; and there are buildings shooting skyward. Since I had been with my wife and my children one summer on the observation level in one of the twin towers, I tried to remember those buildings not destroyed but proudly standing. The picture of them whole was gone from memory, but at least I was there where they had stood.

The best was the modern white subway station that has been built. Its curving walls caught one’s attention as an example of a noted Japanese architect’s work. We went inside, where on the top floor we caught a glimpse of the floor far below filled with people. I am still not sure where the trains arrive and depart. We descended one more level closer to the floor below, but we still seemed skyward.

As I looked below, I remembered when I first heard about the 9/11 tragedy. Then, in 2001, I was the rabbi in Scranton. Sitting in my office, our computer specialist, Sam Green, rushed in: ”Rabbi, something terrible has happened in New York.”

Two and a half months later, in November 2001, my congregants and I took a trip to New York’s East Side. Our arms were filled with gifts we had brought. We handed them out to anyone we met on the sidewalk.

Joyfully we said, “We’re glad you are alive. God bless you!” ■