Isi Leibler, 86, a longtime leader of Australian Jewry who is a religiously observant man, moved all his life in both religious and secular circles, as well as in non-Jewish spheres. But he shares Ben-Gurion’s opinion about miracles, and believes that sometimes, leaders have to help them happen.

Just past bar mitzvah age when the State of Israel was born, Leibler still regards the realization of the centuries-old dream of the Jewish people as a modern-day miracle.

“If there’s one thing that runs through my mind all the time, it’s the fact that from the outset, the very day when Israel was declared and when the Russians and Americans who were engaged in the Cold War both agreed on the State of Israel, it was the beginning of a series of miracles, which to my mind have continued to this very day,” he says.

We are seated in Leibler’s comfortable study in his penthouse apartment in Jerusalem, around the corner from the residences of the prime minister on one side and the president on the other.

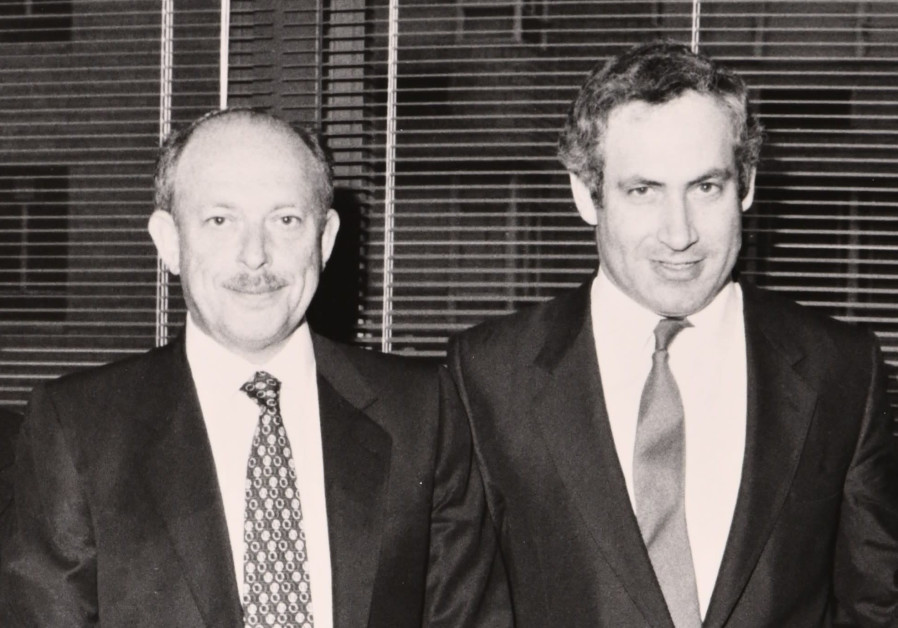

Leibler has met almost all the presidents and prime ministers of Israel, as well as many leaders from other parts of the world, and enjoyed close relationships with several Australian premiers.

One of the first prime ministers he met was Menachem Begin when the latter – as leader of the parliamentary opposition – visited Australia several years before winning the 1977 election. “He made a tremendous impression on me,” recalls Leibler, who regards Begin as one of his heroes.

During his visits to Russia before the Iron Curtain was lifted, Leibler encountered many Soviet refuseniks, whom he calls “Sharansky’s predecessors.” Some, including nuclear physicist Prof. Alexander Lerner, known as the doyen of the refuseniks, became close friends. Leibler credits refuseniks and Prisoners of Zion with changing the course of Jewish history.

“These people were the miracle that to my mind brought about not only a revolution in Jewish life and a critical contribution to the long-term values in Israel, but helped to bring about the fall of the Russian totalitarian empire,” he says. “And to me, that is as great a miracle as any.”

Leibler regrets that these Jews are not recognized in Jewish history for the cardinal role they played in “changing the whole way the Soviet Union behaved” under Mikhail Gorbachev’s Perestroika revolution.

“I salute them,” he says, citing “their ability to withstand the pressures of standing up alone against a powerful, totalitarian country, despite being sent to Siberia and being put in prison.”

Heroes in those days, whose names frequently appeared in the international media when they came to Israel, just became ordinary human beings living in anonymity, but in Leibler’s eyes, “They are the greatest heroes of this generation of Jews.”

Aware from personal experience with KGB agents of the extent of brutal Russian antisemitism, Leibler, still in the context of miracles, sees KGB-trained Russian President Vladimir Putin as “a remarkable character.” He is a despot on the one hand, but at the same time a leader “who sends Rosh Hashanah greetings, which nobody in Russian history has ever done.”

“Putin came to Israel first after his election, and he says the people in Israel who come from Russia are his family,” Leibler says. “This is all incredible stuff.”

HAVING READ the recently published comprehensive biography of Leibler by Australian historian Suzanne Rutland – Lone Voice: The Wars of Isi Leibler (Gefen Publishing Company, 2021) – we tried to steer the interview in different directions. The book was officially launched via Zoom on March 16 by Bar-Ilan University, with Leibler being interviewed by veteran Israeli journalist Ehud Ya’ari after greetings from BIU President Prof. Arie Zaban, former Australian prime minister John Howard, Health Minister and former Prisoner of Zion Yuli Edelstein and Justice Elyakim Rubinstein. Rutland and Leibler’s granddaughter Abigail, a BIU student, also spoke at the launch.

While the book contains so many diverse vignettes of Leibler’s life, including his role in facilitating diplomatic relations on Israel’s behalf with China and India, it was obvious that for him, his greatest achievement was in drawing world attention to the plight of Soviet Jewry.

Leibler is particularly proud of the fact that in 1962, despite being “under enormous pressure and resistance from the left wing,” he was able to persuade the Australian government to introduce the plight of Soviet Jewry in the agenda of the UN.

“We have to be grateful to Australia,” he says. “They were the first ones to raise the issue, and also to call for an end to antisemitism and for aliyah. I think Australia played a very important role in showing how there’s no need to shut one’s eyes to this kind of discrimination. This would never have happened if Jews had not pressured. There’s no such thing as pleading. You have to be able to go on two levels – a public level of protest, and the private level of silent diplomacy. They go side by side; neither works by itself.”

At the time, there were deep divisions in Israel as to whether the government should take a public position on the matter, yet once Australia, a non-Jewish state, had done this, “it was clear that the Jewish state must take a stand.”

Once that was decided, Israel made an all-out effort, and Leibler met some very colorful people engaged in this mission. He developed a close relationship with, among others, British writer Emanuel Litvinoff, who wrote a newsletter called “Jews in Eastern Europe.”

Leibler’s great fear, he tells us, is that “unless there is a dramatic change, we are going to lose huge numbers. A large proportion of the so-called cultural or secular Jews are just going to disappear.”

He voices his concern that a large number of American Jews are Jewish in name only, and that “many of them are engaged in proving that as Jews, they can be anti-Israel.”

As a Jewish leader – he served as president of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry (from 1978 to 1995) as well as the World Jewish Congress’s senior vice president and chairman of the Governing Board – Leibler did not indulge in cronyism. He had no compunction about criticizing leaders of government or of organizations and institutions if he thought that what they were doing was morally wrong and reprehensible. He attributes this attitude to being raised in a home overshadowed by the Holocaust.

“I grew up in a household where the darkness of the Shoah was ever-present. We didn’t know what happened to my grandparents, if they’d been gassed,” he says. “This was a frequent discussion at the dinner table.”

In addition, both his parents – though relative newcomers to Australia – were leaders of Jewish communal organizations. “I was brought up in this atmosphere and also told that communism was an evil, not an evil like Nazism but an evil that was anti-Jewish. All of this had an impact on me, and when I grew up, I said to myself that the Jews in the Western world did very little to save their brethren. They were not out in the streets because they were frightened of antisemitism. Today we live in a free world and it’s the obligation of every Jew to stand up and to protest publicly.”

In advocating for public protests on behalf of Soviet Jewry, Leibler, when he was barely 30, stood up against the formidable Nachum Goldmann, the founder and long-time president of the World Jewish Congress. Goldmann believed in appeasement, and saw no hope of doing anything with the Russians.

The brash young Leibler had a public confrontation with Goldmann, which with hindsight, he believes was the turning point in his career. Until then, Goldmann was the uncrowned “king of the Jews.” For a young man from Down Under to stand up in a huge hall and argue with Goldmann was an exercise either in courage or foolhardiness. It turned out to be the former.

Leibler received a standing ovation, which more than half a century later, he refers to as “an amazing experience.”

He still remembers what it was like before there was a Jewish state. It pains him that very few American Jews “appreciate what the Jewish position was, the powerlessness that we faced before there was a Jewish state.”

He warns that if the current situation is not rectified, there will be small groups of Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews in the Diaspora, but the vast majority of the rest will disappear.

He is, however, comforted by the fact that “Israel is growing from strength to strength,” and he believes that more Jews will come to the Jewish state either because of antisemitism or because this is the only way they can be sure that they will have Jewish grandchildren.

Asked if the Chief Rabbinate is not alienating Jews from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia by questioning their Jewish identity and refusing to recognize those converted abroad, he says, “I wish we could find a Chief Rabbinate that was more humane and flexible, rather than one that tries to show how extreme it is. We have a Chief Rabbinate and a religious political leadership competing with one another to show how each is more extreme than the other.”

Some years ago, Leibler was among the first to write from a religious-Zionist viewpoint that the Rabbinate is alienating Jews. His attack against religious extremism was so powerful that it was translated into 10 languages. He wrote that if religious extremists are not curtailed, Judaism itself will be undermined.

He is convinced that most haredim (ultra-Orthodox) – if they want to survive economically – will have to do national service and go to work, because the status quo cannot be sustained. Nonetheless, he does not believe that the haredi sector of the population poses the threat that many others fear.

He does not hide his admiration for Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, whom he regards as “the greatest prime minister that we’ve ever had,” but, he says, “there’s an end to everything. I believe that the time has come for him to retire graciously.”

Still, Leibler says the question of who to vote for is difficult for him and many Israelis, because although they might like to see Netanyahu retire with dignity, “there is no clear emerging leader to take his place.”

Leibler argues that the present situation of temporary coalitions coupled with a lack of cabinet responsibility cannot continue, because it results in what is basically “a dictatorship by one man who is being exploited by the haredim for their own narrow causes, to the extent that they’re causing deep anguish and concern to the masses of people in the country.”

Asked whether there is anyone he favors as a future leader, Leibler replies that he could think of a dozen potential candidates, “but I wouldn’t name them.” However, he is willing to define what he believes a leader should be.

“Leaders have an obligation to fight for justice, rather than look towards votes. No leader is worth being considered as such, if he’s just going to look at the Gallup polls. The idea is to get people to follow you if you know what’s right.”

He detects this in some politicians, but not enough. He is hopeful that internal rifts will mellow, and notes that many haredi Jews are already becoming integrated into mainstream Israeli society, and women are getting increasingly involved.

“All these things suggest that in the long term, we’re on the right track and will continue to be so,” he says.

Despite all Israel’s flaws, Leibler, who made aliyah a little over two decades ago, remains optimistic as he looks into the future.

“I see Israel in 20 years’ time as more powerful, more stable, and hopefully politically, on a more even keel than it is today,” he says. “Israel’s growth into the mini-superpower that we are today is nothing short of miraculous. There’s no country in the world that has risen from the depths that we were in and turned into what we are today. And that miracle has been continuing for the last few years, with things like energy and water, and other factors coming into our life, and military superiority, that we could never have dreamed of.”

Leibler had wanted to settle in Israel while he was still a student, but his father’s death delayed his aliyah. Today, surrounded by three generations of his family, he has more than fulfilled his dream. He is grateful for a life of miracles, some of which he engineered, although he is too modest to say so.

“In my twilight years, I look back and say I’ve been privileged to live through one of the most tumultuous and rewarding periods in Jewish history, starting off with the darkest time we’ve ever encountered,” Leibler says. “And I’m looking forward to my children and grandchildren and great-grandchildren inheriting a much better world.”