Purim is undoubtedly a time of joy. It is the time set to celebrate Queen Esther and the miraculous salvation of the Jewish people from the hands of the evil Haman. People wear costumes, give food and drink to friends and neighbors, eat the traditional hamantaschen. People attend comical Purimshpil performances and raucous Adloyada parades.

However, Purim is much more than that: it is a time to defy evil and pursue social justice. In addition to donating charity to the poor, Jews observe the commandment of reading the Scroll of Esther (the “megillah“) aloud, so that everyone will know about Haman’s downfall, when he was hanged with his sons on the very gallows he had prepared for Mordechai the Jew.

The image of Haman has been one of the most common epithets used to identify the contemporary enemies of the Jews over the centuries, including Pope Gregory I, Tsar Alexander III, Adolf Hitler and Yasser Arafat.

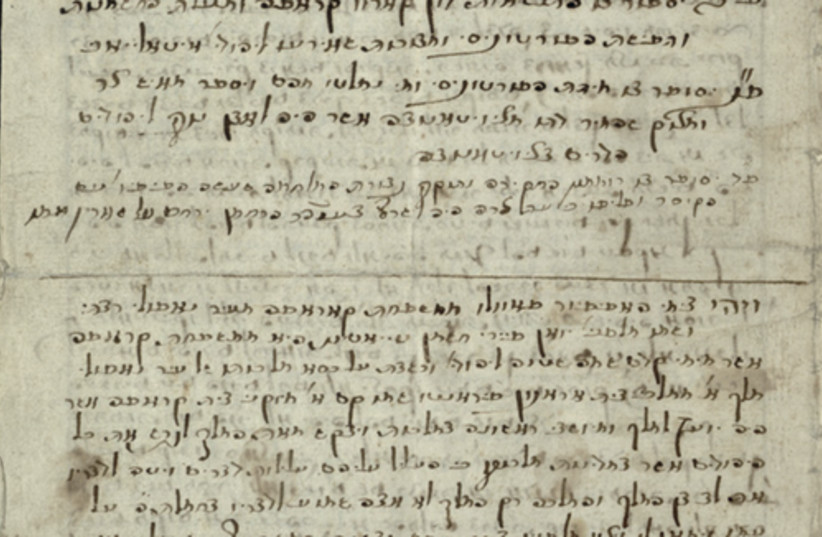

The Hebrew chronicle Divre ha-yamim shel ha-apifior Paolo ha-revi’i ha-niqra Teatino (The Chronicle of Pope Paul IV, Known as the Theatine) also features Haman. The work is contained in a nineteenth-century manuscript in Italian cursive script, today held at the National Library of Israel. No other examples of the work, including the original, are known.

The author of this remarkable work was the moneylender Benjamin Neḥemiah ben Elnathan (also known in Italian as Guglielmo di Diodato), whose family had settled down in the city of Civitanova in the March of Ancona, after the expulsion of the Jews from the Kingdom of Naples in 1540-41.

THE CHRONICLE retraces the four years of Pope Paul IV’s pontificate (1555-59), which caused a radical change in the attitude of the Church towards the Jews. Soon after rising to power, the pope, whose given name was Gian Pietro Carafa, unleashed a number of cruel impositions and restrictions. They were published in the July 1555 papal bull known as Cum nimis absurdum, and included the establishment of ghettos and the requirement that Jews wear yellow badges.

Under the rule of Paul IV – the former cardinal-inquisitor, who, among other things, played a fundamental role in the burning of the Talmud in Campo de’ Fiori in Rome in 1553 – the Roman Inquisition was substantially expanded and strengthened.

In 1556, one of the darkest chapters in the history of Italy Jewry was written when twenty-six Portuguese Jews, who had been baptized in Portugal in the late fifteenth century and who then returned to Judaism after moving to Italy, were declared heretics and burned at the stake in Ancona.

In 1559, the same Benjamin Neḥemiah ben Elnathan, his brother Samuel, and four other Jews from Civitanova were arrested by the Roman Inquisition, accused of having tried to convert a Franciscan friar to Judaism and having thrown stones at certain sacred Christian images. The chronicler recounts that a number of slanderers were behind the accusations, including Aharon ben Menaḥem, a Jewish man who had converted to Christianity and became known as Giovan Battista Buonamici.

Benjamin compares this apostate to the evil Haman, because like the latter, he used his eloquent manner of speaking to destroy the Jews. According to the account:

“…in the first days of his conversion, he made himself seem like a man who loved the people of Israel… but his heart was full of abominations, then he became an enemy of the Jews and injured them with his speech. He was an evil man and an enemy like Haman who used his speech in a deceitful manner.”

THIS IS not his only mention of Haman. Indeed, Benjamin associates Haman with the pope’s nephew and counselor, Cardinal Carlo Carafa, who, in another passage of the chronicle, is accused of committing murders, raping virgins, steeling goods and perpetrating other shameful deeds.

In the chronicle, Benjamin recounts the cardinal arriving at his dead uncle’s bedside, and curses the two evil men with clear reference to the death of Haman and his sons on the gallows: “Both of their burning bodies may be hung on a tree and their souls roasted in the fire!”

Echoing the story of Haman’s downfall, following Paul IV’s death, his successor arrested Carlo Carafa and dragged him through the streets of the Vatican. Moreover, there was a custom to free prisoners following the death of a pope, so Benjamin and other Jews were released from the Inquisition prisons.

According to his own account, Benjamin and his compatriots went to meet the Duke of Civitanova to ask for his permission to return home. He granted their request and before they returned to Civitanova, they witnessed the destruction of the previous pope’s statue on the Capitoline Hill in Rome.

The manuscript generally depicts Paul IV as evil, and even something of a devil, with the author often cursing him and including him “in the company of the evil”, along with Balaam – the non-Israelite prophet who cursed the people of Israel (Numbers 22-24).

Benjamin also links Paul IV to Amalek, the eternal enemies of the Israelites who were first encountered during the forty-year trek in the wilderness following the exodus from Egypt, and who, according to tradition, were among Haman’s ancestors.

In the biblical account, Amalek’s attack was the first war Israel experienced, and the victory marked a shift in the history of the Jewish people. God ordered Moses to “Inscribe this in a document as a reminder, and read it aloud to Joshua: I will utterly blot out the memory of Amalek from under heaven!” (Exodus 17:14).

In this sense, the writing of a detailed chronicle on the “evil pope” and his reign was perceived by Benjamin as a moral commandment. Like the Scroll of Esther, The Chronicle of Pope Paul IV narrates the miraculous salvation of the Jewish people from the evil plots of their enemies, who are ultimately defeated.

Martina Mampieri is the author of Living Under the Evil Pope: The Hebrew Chronicle of Pope Paul IV by Benjamin Neḥemiah ben Elnathan from Civitanova Marche (16th cent.), published in 2020 by Brill.

This article originally appeared on The Librarians, the official online publication of the National Library of Israel dedicated to Jewish, Israeli, and Middle Eastern history, heritage and culture.