The Mishna’s tractate Tamid describes the blood and gore of the daily Temple sacrifice in graphic detail. “...He then began to flay it until he came to the breast. When he came to the breast he cut off the head and gave it to the one who merited [bringing it onto the ramp]… He took the fat and put it on top of the place where the head had been severed… He then took the left hind leg and cut it off and gave it to the one who had merited [bringing it onto the ramp].”

For some of us, these passages might recall scenes of Rocky Balboa training in a Philadelphia meat packing plant or the most gruesome passages from Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. For Rabbi Yaakov Nagen these passages allude to the sublime, lyrical, erotic, love poetry of the Song of Songs.

The Mishna, redacted by Rabbi Yehuda Hanassi around the turn of the second century, is frequently looked upon as a legalistic, dry and even tedious work. Nagen, in his aptly named The Soul of the Mishna, presents the Mishna as an elegantly crafted, inspirational, spiritual text. The book culminates in its final chapters which take on one of what many would find to be the Mishna’s most distasteful tractates and the least likely to inspire.

Reading the Mishna

Carefully reading the Mishna’s description of the priest who “draws it [the sacrificial animal] with him to the slaughterhouse, and those who […] bring the limbs up after him” (Tamid 3:5), Nagen notices an echo of the young lover’s plea to her beloved in the Song of Songs, “draw me near and we will run after thee” (Song of Songs 1:4). Moreover, Nagen notices that the Mishna’s instructions to tear the heart of the animal sacrifice appears in the fourth of Tamid’s seven chapters and is the second of that chapter’s three subsections (mishnayot). This places the instructions regarding the heart of the sacrifice at the very heart of the tractate. According to Nagen, the Mishna is presenting the sacrifice as “a symbolic realization of the verse ‘And tear your heart, and not your garments, and turn to the Lord your God’ (Joel 2:13).” Suddenly, these passages are much more than descriptions of ancient sacrificial rituals. They are expressive articulations of passionate yearning for the Divine and the transcendent significance of a broken heart.

These snippets of The Soul of the Mishna do not do justice to the book’s overall analysis. They also are not necessarily typical examples. Much of the analysis is of passages that are much more palatable, and the interpretations do not always present such stark contrasts to the first readings of the original that they interpret. Nevertheless, in their poignancy, these samples are useful to demonstrate the book’s power in reframing the Mishna and its ability to demonstrate what careful readings can uncover in this classic text.

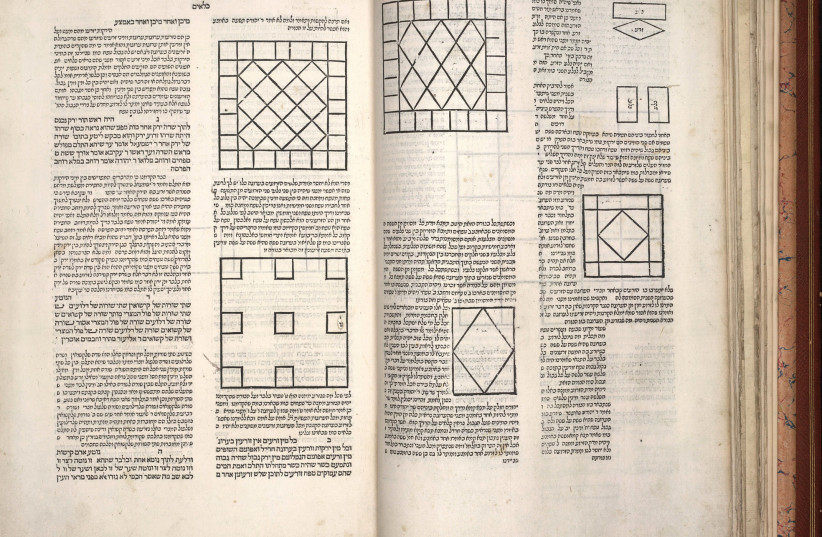

TO CREATE this refreshing and original interpretation of the Mishna, Nagen calls upon a whole host of resources, from classic interpreters of the Mishna to the Kabbalah, to analysis of literary structures. Particularly striking is Nagen’s use of academic scholarship. Skimming through the notes and bibliography of The Soul of the Mishna, one encounters PhD theses and books and papers written by professors of Judaic studies.

Those who encounter Torah study in the context of the academy might wonder about the value of critical study for Jewish life. The typically cold objective stance toward the text and the focus on seemingly pedantic matters like manuscript variants can feel at odds with more traditional Torah study’s modes of shaping a holy life and developing moral character. Reading The Soul of the Mishna, I couldn’t help but recall a conversation that I once had with an esteemed professor of Jewish studies in which I challenged him about the spiritual value of critical scholarship. He responded that academic Talmud study is valuable as an expression of the pursuit of truth.

In many ways, The Soul of the Mishna provides an alternative response. In this work, modern approaches to textual analysis are more than pursuits of mundane truths; they become part and parcel of the pursuit of uncovering the meaning of life that is at the heart of Torah study. Indeed, this work at its core is an amazing endeavor to cull from the Mishna’s content, structure and intertextuality insights into the meaning of life in general and Jewish life in particular.

In its zealousness for that end, there are moments when the book might push beyond the limits of a compelling read based in the text (peshat), but any excesses are more than forgivable in light of the gems of understanding and inspiration that it offers. ■

THE SOUL OF THE MISHNA

By Yaakov Nagen

Koren Publishers

436 pages; $29.95