The French writer Guy de Maupassant once wrote a startling short story called “The Artist.” It told of a man who was a knife-thrower in the circus. His “target” was his wife, who stood against a wood plank. He would trace her outline in knives, never letting the knives touch her but coming exquisitely close with each throw. Each time the knife-thrower would plant a knife near her, she would utter a small laugh.

The knife-thrower tells the narrator of the story that his wife has, in fact, been cheating on him, and it would be the easiest thing in the world to hurt her or even kill her and say his hand slipped. But he cannot, not because of love, but because he is a professional. He cannot bring himself to mar his art. Her laughs, he says, are mocking, knowing he will never injure her.

When I first read that story it reminded me of Primo Levi’s tale of bricklaying in Auschwitz. The professional bricklayer detested the Nazis. They ordered him to build a wall. Yet despite his loathing, he built a perfect wall. He, like the artist, took great pride in his work, and would not ruin it no matter how powerful the motivation.

In these very different stories is the clue, I believe, to a paradox of Passover. The Seder plate is filled with representational items. The bitter herbs represent the bitterness of slavery, the shank bone the sacrifice, and so forth. The saltwater reminds us of tears. The mimetic function is apparent – each is somehow “like” what it recalls. Yet there is one item that violates this stricture – the haroset.

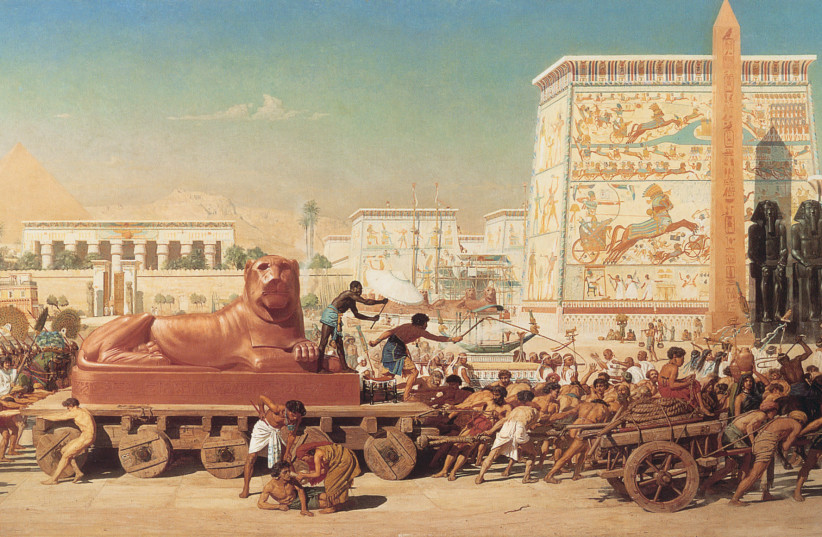

Haroset is intended to represent the mortar of the bricks the Israelites laid in Egypt. Yet haroset is sweet. How could that be?

We know that the Egyptians deliberately embittered the lives of the Israelites. Slavery was unspeakably awful. Yet it is possible that like the bricklayer in Auschwitz, even in the most oppressive circumstances, there is some touch of satisfaction in a job well done. Even the taskmaster cannot rob the slave of the sense of dignity in his or her own work.

Perhaps the haroset is intended to remind us that work, even when coerced, has an intrinsic value. Not that anyone would choose to work in slavery of course; it was degrading and humiliating and painful and often fatal. But a spark of the ideal of work itself, of actually using one’s body to build in this world, might endure even in the most terrible circumstances.

Remember that the Torah advises us: “Six days shall you labor and on the seventh shall you rest.” We tend to focus on the day of rest, the innovation in human history. We might equally focus on the Torah’s assumption that we will use the other six days to work. Work itself is both a Divine imperative and a testament to human creativity and dignity.

Passover recounts work at its worst of course – the labor of slavery. It is Sukkot that we know as Z’man simchateinu, the time of our joy. Perhaps the sukkah is a time of joy because on Sukkot we willingly build something – a sukkah. It is work, real labor, and gives us a sense of accomplishment.

I have participated in events with Art Bilger’s organization Working Nation (workingnation.com), which is trying to rethink the nature of work for the years to come. As technology changes the world and many jobs that were once standard disappear from the public sphere, we need to figure out how to ensure that the dignity of labor remains for those whose jobs are imperiled or vanishing.

Slavery reminds us of work intended to belittle and wound. The haroset, however, hints at the truth that work is also a way of sweetening life. Let us hope that liberation to accomplish and achieve will be part of our collective future.

Chag Sameach! ■

The writer is Max Webb Senior Rabbi of Sinai Temple in Los Angeles and the author of David the Divided Heart. On Twitter: @rabbiwolpe.