Much of life is about rhythm: finding a rhythm, getting into a rhythm, enjoying the rhythm.

And one of the most difficult things about losing a loved one – as I did when my father passed away two months ago – is that it disturbs, interrupts and changes that rhythm. All of a sudden a dominant beat that was always part of that rhythm just vanishes.

The Jewish laws of mourning understand this, and are structured in such a way as to help the mourner recover the rhythm after the loss of a close relative. But it is a slow, gradual process starting with the seven days of shiva, followed by the 30 days of shloshim, and culminating with the first yahrzeit that marks the end of the 12-month mourning period.

The goal is a return to life’s regular tempo. Not at once, but gradually. It’s all about the rhythm.

The obligation to say kaddish three times a day for 11 months – necessitating praying in a minyan – creates a definite rhythm to the day.

The mourner’s kaddish itself – recited numerous times across the three daily prayer services – is itself very rhythmic.

“By the constant, hypnotic repetition, morning and night, of the words chayim (life) and yamim (days) and olam (world),” Maurice Lamm wrote in The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning, the kaddish is “dramatic in its rhythms and word-music.”

IT’S BEEN 37 years since I was last obligated to say kaddish, following the death of my mother. When she passed away I was an unmarried student in the American midwest, studying journalism at the University of Illinois in Champaign-Urbana.

That year – my mom died at the very beginning of the academic year – was dedicated more to making sure I had a daily minyan, than to my studies. Though there were 30,000 students at the school, it wasn’t always easy to find 10 Jewish males willing to gather three times a day to pray.

The three Jewish fraternities on campus volunteered to help, sending two or three guys for each service. Then there were the handful of regulars at Hillel. But often that was just not enough.

I remember a couple of times going across the street to a smoke-filled cafe called the “Daily Grind,” channeling my inner Chabadnik, scanning the tables for a Jewish-looking man, approaching him, asking if he was indeed Jewish, and – if so – whether he would help complete a minyan. In what always left me with a great sense of Jewish solidarity, the answer was always “yes.”

This time, as I say kaddish for my dad, it is completely different. I’m in Israel, not in central Illinois, and finding a minyan is never a chore, no hassle whatsoever – one of the unsung benefits of living in the Jewish State.

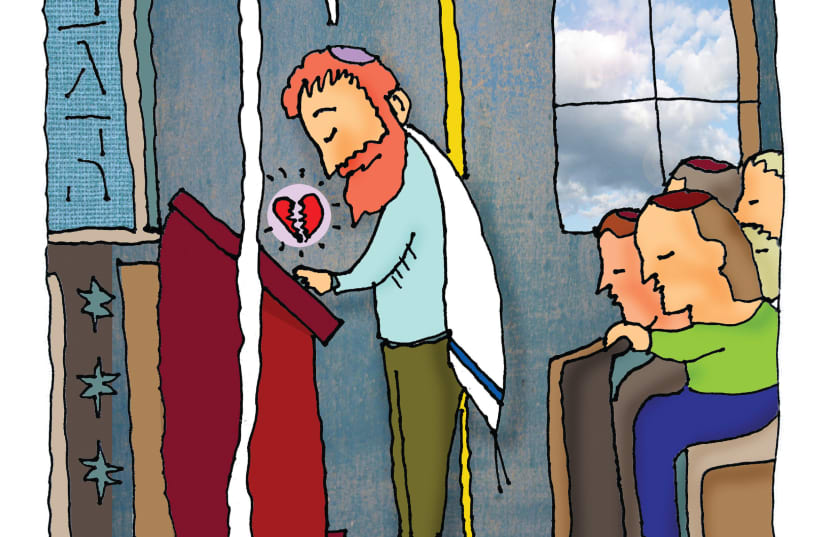

IN ADDITION to making tremendous psychological sense, the constant recitation of kaddish, as well as the custom among Ashkenazim that the mourner leads the weekday prayer services, serves as a thrice-daily reminder that I am in mourning.

Although that reminder may be depressing and heavy, it is also wise. One may want to get back into life’s rhythm right away, but this comes to say, “not so fast, slowly, be cognizant and mindful of what just happened.”The obligation to lead the daily prayers falls on the mourner while he is saying kaddish, and it also falls on anyone commemorating a yahrtzeit (anniversary of a death). In the who-leads-the-davening hierarchy, someone with a yahrtzeit trumps a regular mourner.

This means that if someone in shul has a yahrtzeit, he gets the right-of-way to lead the prayers instead of me. On one hand, this leaves me thrilled, because I get a day off from the pressure of leading the services – not having to worry about fumbling words or going too fast or too slow. But on the other hand, it leaves me feeling bad about myself – what kind of person is happy when someone else has a yahrtzeit?

What kind of person? A person for whom leading the services is a nerve-wracking chore. My father’s death left me a mourner, it didn’t turn me into a cantor. Yet I do it, both because I’m supposed to, and because this too creates a certain rhythm, as well as a sense that somehow I’m helping my dad.

Another part of the Jewish laws of mourning that provide comfort is not going to large festive celebrations during the year of mourning – like weddings, bar mitzvahs or any other type of party. This removes any internal struggle over whether it is seemly to celebrate so soon after the death of a loved one. Halacha says just don’t go.If we’re honest, we’ll admit that while weddings are joyous affairs, we’re not always that excited about going to all of those to which we are invited. If I know the bride or groom and am friendly with one of their parents, that’s one thing. But if it is a perfunctory invitation because the person feels obligated to invite me, then any excuse to get out of it is welcome.

Mourning provides an indisputable excuse.

AND IT’S not only weddings. A close friend’s son had a baby boy recently, and the grandparents – my friends – were hosting a coming-out party for the little tyke, a shalom zachor, on Friday night.

This is a case where I actually would have enjoyed going – though I’m generally not crazy about going out after dinner on Friday night – but, because of my year of mourning, was forced to decline.

My friend, aware of the halachot and the possibility of creating a subterfuge whereby mourners can attend if they have a job to do at the event, said he would let me serve his guests and then do the dishes. That way I would be more worker, than celebrant.

I thought about it for about half a second, and replied, “As tempting as it sounds going out on Shabbat evening to wait on your guests and do their dishes, I think I’m going to pass.”

The laws of mourning are designed to get me slowly back into the rhythm of life, I explained. Not turn me into the domestic help.