“And then halfway through this novel about literary failure, I win the Booker. Which stops it in its tracks, dead. And I think, I don’t know if I can go back to it.”But the feeling passed.“Little by little, I thought, nothing has changed, I’ve won this prize, but that’s luck.”And back he went.Zoo Time, Jacobson says, is a comic novel.“It’s the funniest thing I’ve written, I loved writing it. The ostensible story is about a man who is in love with his wife’s mother.”Ah-hah. Everyday, run-of-the-mill stuff. Bound to end in spectacular, glorious humiliation.“That is the tale... what is actually going on is that it is a novel about the end of novels.”He sketches out the opening scenes.“It begins with him being caught by the police stealing one of his own books from an Oxfam bookshop [a chain of charity shops, often accused of undercutting the book trade], and that happens just after he’s come out of a reading group, a women’s reading group where they’ve said things like ‘I can’t identify with any of your characters,’ ‘why don’t you like women,’ and all this.”Zoo Time is set in a world of closing bookshops, publishers at the end of their tether, people reading only thrillers and children’s books. Pretty much this world, then. It’s probably fair to say that Jacobson is not the biggest fan of the intrusions of the supposed democratic voice on the book trade, literary bloggers and user-generated reviews taking the place of serious literary criticism.“It’s the sheer illiteracy, the wicked democratization of the intellectual life, where everyone thinks that they are entitled to an opinion and they don’t know... they don’t know what a judgment is. They think that if they go ‘I don’t like it’ then they have said something about a book. They don’t know that all they’ve done is said something about themselves.”Which takes us back to the issue of labels, particularly when they are appended to a writer for the sake of convenience more than anything else. It is, technically, correct to think of Jacobson as a “Jewish” writer. He has no quarrel with this per se, but refuses to engage with the label in the reductive sense.“I’m not by any means conventionally Jewish,” he told the American website Nextbook in 2004. “I don’t go to shul. What I feel is that I have a Jewish mind... a disputatious mind. What a Jew is has been made by the experience of 5,000 years, that’s what shapes the Jewish sense of humor, that’s what shaped Jewish pugnacity or tenaciousness.”Jacobson, to his regret, was obliged to cancel a planned visit to Israel, as a guest of the International Writers’ Festival in Jerusalem, on medical advice. He says that he had looked forward to talking about his books, particularly The Finkler Question, not least because many had not been published in Hebrew before his Booker win.“Do you know what they said? ‘Because he is too Jewish!’ Too Jewish for Jerusalem!” It is ironic, but he acknowledges that his concerns as a Jew may not necessarily resonate with an Israeli audience.“The Diaspora Jewish experience, Jews worrying about being Diaspora Jews. I can see that to an Israeli Jew, it is a bit of a luxury.”Does he feel, perhaps, that Israelis have lost the capacity to laugh at themselves?“I don’t know enough about life in Israel. I just don’t know.”But: “There were people who many years ago lamented the idea of an Israel – even before the politics of modern- day Israel – because Jewish culture had become Diaspora culture. What was beginning to define what was virtuous and admirable about the Jews was precisely what they would lose if they then all gathered in one place. Alienation, being the other, the Jewish other.”Humor, he thinks, is one of these key traits. And perhaps giving up on it was part of the trade-off.“It’s almost as if, in one sense, the Jewish state was predicated on a knowledge of that loss. That particular thing, that cleverness, that bitterness, that edgy wittiness. That was our reward for, you know, the terrible life that we lived. But we were prepared, surely we were prepared to lose that for a better life.”

The novelty of success

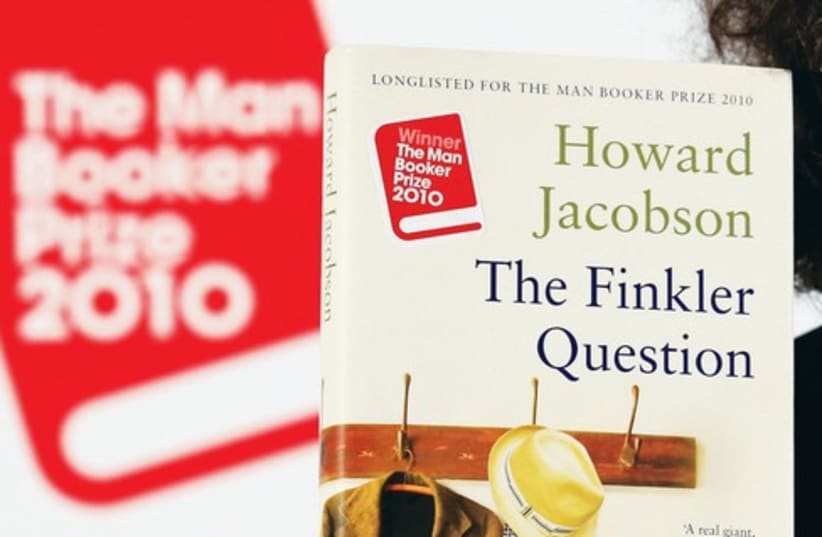

Undeterred by winning the Man Booker Prize in 2010, Howard Jacobson pressed on with his latest project, a novel about literary failure.

“And then halfway through this novel about literary failure, I win the Booker. Which stops it in its tracks, dead. And I think, I don’t know if I can go back to it.”But the feeling passed.“Little by little, I thought, nothing has changed, I’ve won this prize, but that’s luck.”And back he went.Zoo Time, Jacobson says, is a comic novel.“It’s the funniest thing I’ve written, I loved writing it. The ostensible story is about a man who is in love with his wife’s mother.”Ah-hah. Everyday, run-of-the-mill stuff. Bound to end in spectacular, glorious humiliation.“That is the tale... what is actually going on is that it is a novel about the end of novels.”He sketches out the opening scenes.“It begins with him being caught by the police stealing one of his own books from an Oxfam bookshop [a chain of charity shops, often accused of undercutting the book trade], and that happens just after he’s come out of a reading group, a women’s reading group where they’ve said things like ‘I can’t identify with any of your characters,’ ‘why don’t you like women,’ and all this.”Zoo Time is set in a world of closing bookshops, publishers at the end of their tether, people reading only thrillers and children’s books. Pretty much this world, then. It’s probably fair to say that Jacobson is not the biggest fan of the intrusions of the supposed democratic voice on the book trade, literary bloggers and user-generated reviews taking the place of serious literary criticism.“It’s the sheer illiteracy, the wicked democratization of the intellectual life, where everyone thinks that they are entitled to an opinion and they don’t know... they don’t know what a judgment is. They think that if they go ‘I don’t like it’ then they have said something about a book. They don’t know that all they’ve done is said something about themselves.”Which takes us back to the issue of labels, particularly when they are appended to a writer for the sake of convenience more than anything else. It is, technically, correct to think of Jacobson as a “Jewish” writer. He has no quarrel with this per se, but refuses to engage with the label in the reductive sense.“I’m not by any means conventionally Jewish,” he told the American website Nextbook in 2004. “I don’t go to shul. What I feel is that I have a Jewish mind... a disputatious mind. What a Jew is has been made by the experience of 5,000 years, that’s what shapes the Jewish sense of humor, that’s what shaped Jewish pugnacity or tenaciousness.”Jacobson, to his regret, was obliged to cancel a planned visit to Israel, as a guest of the International Writers’ Festival in Jerusalem, on medical advice. He says that he had looked forward to talking about his books, particularly The Finkler Question, not least because many had not been published in Hebrew before his Booker win.“Do you know what they said? ‘Because he is too Jewish!’ Too Jewish for Jerusalem!” It is ironic, but he acknowledges that his concerns as a Jew may not necessarily resonate with an Israeli audience.“The Diaspora Jewish experience, Jews worrying about being Diaspora Jews. I can see that to an Israeli Jew, it is a bit of a luxury.”Does he feel, perhaps, that Israelis have lost the capacity to laugh at themselves?“I don’t know enough about life in Israel. I just don’t know.”But: “There were people who many years ago lamented the idea of an Israel – even before the politics of modern- day Israel – because Jewish culture had become Diaspora culture. What was beginning to define what was virtuous and admirable about the Jews was precisely what they would lose if they then all gathered in one place. Alienation, being the other, the Jewish other.”Humor, he thinks, is one of these key traits. And perhaps giving up on it was part of the trade-off.“It’s almost as if, in one sense, the Jewish state was predicated on a knowledge of that loss. That particular thing, that cleverness, that bitterness, that edgy wittiness. That was our reward for, you know, the terrible life that we lived. But we were prepared, surely we were prepared to lose that for a better life.”