With an eye on the situation here in the territories, it is especially seductive to imagine that Northern Ireland could be a model for success. Unfortunately, though, whatever persuaded the IRA to put its weapons beyond use may not work with terrorist groups such as Hamas and Islamic Jihad. Decommissioning militias is a notoriously tricky business - one involving issues of balance of power, ideology, ethnic differences and external factors that make each case a maddeningly unique challenge to solve.

An in-depth look at three attempts at disarming militias - in Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Lebanon - shows how difficult that can be. One was a success, the other two failures. All of them, however, suggest that the chances of Hamas and Islamic Jihad voluntarily transitioning into non-violent political life are slim to none.

INDONESIA

A once-sovereign sultanate with ambassadors in Europe, Aceh was conquered by the Dutch in 1873 and over 70 years later was incorporated into the rest of Indonesia when the latter won its independence from the Netherlands.

"The Acehnese were keen on being part of Indonesia," says Kirsten Schulze, a historian at the London School of Economics, "but they expected special status for their region, which they never got."

Such a disappointing turn of events bred separatist feelings, and in 1976, a prominent local businessman established what is popularly known as the Free Aceh Movement, or Gerakan Aceh Merdeka (GAM).

GAM roundly condemned Indonesia as a Dutch-created fraud "to cover up Javanese colonialism" and then took up arms against the central government. After years of fighting, GAM and Jakarta reached two cease-fires in 2000 and 2002 - both of which unraveled, each side accusing the other of acting in bad faith.

Ultimately, it would take the tsunami of December 2004, which drowned 128,000 Acehnese, to jumpstart the stalled peace process. The natural disaster convinced the separatists, already hammered by the military, to forestall demands for independence, and in August, the two warring parties signed a Memorandum of Understanding.

This agreement created a joint EU-ASEAN Monitoring Mission in Aceh, which, among other things, is meant to oversee "the demobilization of GAM and monitor and assist with the decommissioning and destruction of its weapons, ammunition and explosives."

To that end, the mission employs some 250 civilian personnel in 11 district offices throughout Aceh, and, so far, has been a success. Voice of America reported on September 30 that the GAM has already given up a quarter of its weapons.

In return for disarming, GAM gets amnesty for its members, the withdrawal of non-native Indonesian troops and very strong regional autonomy - which in conservative Aceh, means a volatile mix of democratic reform and Islamic law.

As for the unfulfilled dream of independence, Bakhtiar Abdullah, the group's spokesman in Sweden, sounds quite pragmatic: "We'll let the Acehnese people decide what they want. After all, isn't that what democracy is all about?"

SRI LANKA

But before hopeful comparisons are made with the Palestinians, Indonesia has fared much better than other countries in similar circumstances. Sri Lanka, for example, has also fought an exhausting civil war since the 1970s, yet it was rebuffed in April 2003 when it offered its mostly Hindu Tamil separatists in the north and east a measure of local autonomy in exchange for laying down their arms.

And why should the rebels have accepted the deal? After all, not every terrorist group is as lightly equipped as GAM. The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Ealam (LTTE) have tanks, rockets and a budding air force, allowing them to control about 20 percent of the tropical, South Asian island.

"The LTTE has massive support among the Tamils," says N. Manoharan, a senior fellow at New Delhi's Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies. "It has its own police, checkpoints, education and financial ministries, and a judiciary wing." And all because of racial quotas.

When Sri Lanka (then called Ceylon), got its independence from Britain in 1948, the majority Sinhalese went about reversing colonial-era policies they viewed as pro-Tamil.

For example, Sinhala was made the official language, and an affirmative action program was instituted for Sinhalese university students.

In 1972, the same year that Buddhism became Sri Lanka's state religion, a bookish Tamil teenager named Velupillai Prabhakaran formed what would later become the LTTE - a premier terrorist outfit famed for its cult of personality, suicide bombings (it invented the bomb belt), and assassinations of two heads of state.

Prabhakaran once told a Tamil magazine how stories of empires and heroes which he read as a boy fueled his militancy. "Why shouldn't we take up arms to fight those who have enslaved us: this was the idea that these novels implanted in my mind," he said.

But far from a fairy tale, Prabhakaran's secessionist war in Sri Lanka has snuffed out 64,000 lives. In 1987, a peace-keeping force from neighboring India intervened but failed to disarm the Tigers; likewise, a cease-fire in the mid-1990s quickly disintegrated.

Then, in February 2002, a militarily exhausted LTTE and Sri Lankan government signed a cease-fire agreement, and Sri Lanka Monitoring Mission spokeswoman Helen Olafsdottir says, "there has not been a major outburst between the two forces for the past three and a half years."

But neither cease-fire nor tsunami has brought real peace. In fact, the Tigers have used the precious time-out to rebuild their forces, now 12,000 strong, and to eliminate Sri Lanka's network of informers in Tamil areas, Manoharan notes.

So will it be Indonesia or Sri Lanka in the territories? Keep in mind that, while Palestinian terrorists may not yet have tanks or katyushas, there were an estimated 50,000 illegal weapons floating around the West Bank and Gaza before September's security breach along the Gaza-Egyptian border.

LEBANON

Now, ideological rivalry and recent clashes between the Palestinian Authority and Hamas would suggest a civil war-type scenario. Actually, though, the situation in the territories more closely resembles that of Lebanon: a state being pressured by outsiders to disarm a militia not posing a direct challenge to its well-being - in this case, the radical Shi'ite Islamist group Hizbullah ("Party of God").

Indeed, Hizbullah is the very epitome of a terrorist group playing at political party.

Formed in 1982, it is the only sectarian militia to have survived the Lebanese civil war, which began seven years before with a fatal drive-by on an East Beirut church. Every other faction signed on to the 1989 Taif Accords, which introduced political reforms in the country's unstable confessional system and called for "the disbanding of the Lebanese and non-Lebanese militias..."

However, the Shi'ite Islamist group was excluded from the Syrian-brokered accords on the grounds that it served Lebanese national interests by fighting the Israeli occupation in the south. When the IDF withdrew from Lebanon in May 2000, Hizbullah committed itself to "liberating" the Shaba Farms, an area which the United Nations says really belongs to the Syrians.

And what if Israel were to pull back again?

"It would be a great victory for the resistance if Israel truly withdraws from Shaba Farms," Hizbullah Deputy Secretary-General Naim Qassem was quoted two months ago in Lebanon's Daily Star as saying, "but there will be no negotiation over disarmament in return for Israel's withdrawal from the farms."

Most Lebanese want to see Hizbullah decommission its weapons, but, so long as the Shi'ite Islamists do not try to overthrow the government or provoke an Israeli invasion, the preferred way of resolving the issue is through internal dialogue. The last thing anyone wants to do is ignite another civil war, says Eyal Zisser, a Lebanon expert at Tel Aviv University.

So, as in the Palestinian case, pressure to disarm comes from the Americans and Israelis.

In September 2004, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1559, which echoes the disarmament language of the Taif Accords - without giving a free pass to the Party of God. This year, Hizbullah lost its patron when the Syrian army was forced to withdraw from Lebanon while a UN resolution calling on Beirut to secure its border with Israel was adopted.

Still, the Party of God continues to bob and weave - hinting to those ready to believe, including EU diplomats, that disarmament is just around the corner.

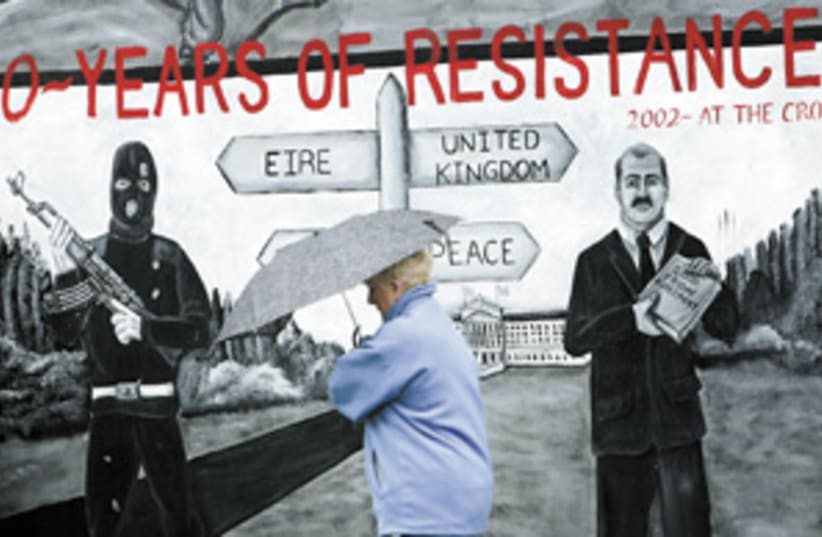

"It baffles me that so many observers cannot see through Hizbullah's games," says Magnus Ranstorp, a terrorism expert at Stockholm's Swedish National Defense College. "Its whole identity is wrapped up in the idea of resistance."

Many are similarly dazzled by the social works of the Palestinian Islamists and, seeking to spare the PA a difficult decision, hope that Hamas and Islamic Jihad can somehow be absorbed within the political system without a shot being fired. But given the cases of decommissioning just reviewed, that is a very unlikely scenario.

| More about: | Velupillai Prabhakaran, Hezbollah, London School of Economics, Palestinian National Authority |