In April 1985, Prof. Yirmiyahu Branover, one of the most well-known Soviet refuseniks, was on a trip to New York from Israel, where he had been teaching at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev in Beersheba.

A devoted Chabad Hassid, he had launched Shamir, an outreach organization for Soviet immigrants to Israel aimed at helping them learn about their Jewish heritage after having been forbidden from it until then.

Branover was surprised when the secretary of the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, called him and told him the Rebbe wanted to see him. This was quite unusual as the Rebbe had ceased most private meetings at the time. He went, and the Rebbe gave him an important message: “Contact the activists in Russia and tell them that they will soon be permitted to practice their religion freely and immigrate if they choose.” The Rebbe asked him to keep this information out of the media.

“Contact the activists in Russia and tell them that they will soon be permitted to practice their religion freely and immigrate if they choose.”

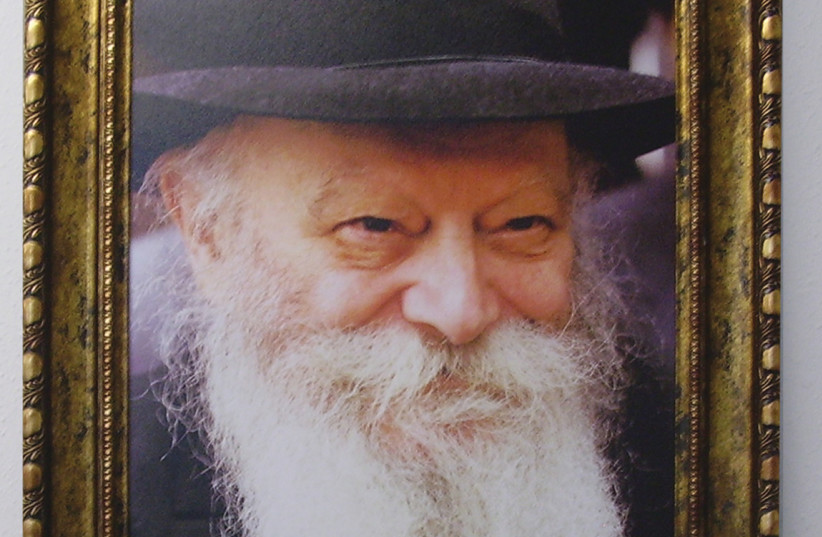

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the Lubavitcher Rebbe

Branover was shocked at this seemingly unrealistic prediction but immediately upon leaving the Rebbe’s office, he began to reach out to Jews in Russia to share the Rebbe’s message. The reaction was one of disbelief. One person told Branover, “We are under KGB surveillance as we speak!” Branover reported the reaction of the Russian Jews to the Rebbe, who responded by writing him a note saying, “Changes are underway but it is not apparent yet.”

A few years later, newly selected head of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev took the unprecedented step of opening the Iron Curtain for immigration and permitting Jews to practice Judaism as they wished.

In June 1992, after Gorbachev had left his position as leader of Russia, he was invited to receive an honorary degree at BGU and Prof. Branover was asked to escort Gorbachev during his visit. As they toured the campus, Branover told Gorbachev the story of what had occurred in 1985, when the Rebbe had told him to instruct Jews in Russia that change was underway.

Gorbachev was astonished, telling Branover, “That cannot be possible. When I took office in 1985, I had no intention of liberalizing Russia. In fact, my plans were the opposite. The idea of glasnost was for outside consumption only, to remove pressure from the West. I had no plan to permit Jewish immigration then. Only later did I change my mind.”

"When I took office in 1985, I had no intention of liberalizing Russia."

Mikhail Gorbachev

When Gorbachev visited Oxford University at a later date, he had a similar conversation with Peter Kalms, co-chair of Shamir and a close confidant of Branover. Gorbachev reiterated to Kalms that he had no plans to free Soviet Jewry when he assumed power and asked, “How did the Rebbe know if I myself did not know?”

How did the Lubavitcher Rebbe know Gorbachev would free Soviet Jewry?

Many believe that Gorbachev’s decision to permit the emigration of Soviet Jews was a result of the massive demonstration organized in Washington in 1987. At the time, there had been a longstanding debate about the best way to pressure the Russian government to change its policy toward Russian Jewry. Many activists, whose intentions were noble, viewed the issue from the perspective of a democracy like the US, asserting that public demonstrations were the best way to pressure the Soviet Union.

The Israeli government supported, and in many ways secretly orchestrated those demonstrations. This was done by the Liaison Bureau (Lishkat Hakesher), a division of the Prime Minister’s Office since the early 1950s. It had coordinated the clandestine activities of the Israeli government in the Soviet Union under the guidance of legendary spymaster Shaul Avigur. The Lubavitcher Rebbe, while cooperating with Avigur on many levels, disagreed about public demonstration. The Rebbe argued that this would only cause the Russians to further dig in their heels, and a more successful path was pursuing quiet advocacy and behind-the-scenes diplomacy.

He would know. From New York, the Rebbe was leading an underground network of Jewish institutions in the Soviet Union and secretly supporting Russian Jews with their spiritual and material needs. When the Israeli government decided to reach out to the Russian Jews in the ’50s, recalled prime minister Yitzhak Shamir at a 1994 memorial for the Rebbe, the Mossad discovered the network active in every city.

In 1969, the Rebbe requested that the Israeli government defer a major demonstration planned before Passover. He believed it would cause the Russians to retaliate and prohibit the emigration of a group already set to leave Russia at the time. At first, the government under prime minister Levi Eshkol considered the Rebbe’s request but when he passed away in February, his successor, Golda Meir, refused. Indeed, in the wake of the demonstration, permission for a large group of Jews to leave the country was rescinded.

The Rebbe clearly had a vision that surpassed general consensus and even expert opinion when it came to the Soviet Union. Still, the question remains. What motivated Gorbachev to bring down the Iron Curtain?

Gorbachev explained his motivations on two occasions. In 1992, in a private meeting with Russia’s Chief Rabbi Berel Lazar, Gorbachev told him that the demonstrations had nothing to do with his decision. The second occasion was to Nehemia Levanon, an Israeli agent in Russia during the fifties who later coordinated the activities of the Liaison Bureau in the US. He wrote in his memoirs that he too met with Gorbachev after he left office, and the former president had told him that the ubiquitous antisemitism in Russia had prompted him to allow immigration.

Today, Jewish life and opportunity in the former Soviet Union is flourishing well beyond what anyone could have imagined in 1985 and in the wake of his passing, Jews the world over owe a great debt of gratitude to president Mikhail Gorbachev. He lifted restrictions on Russian Jewish emigration and allowed Jews remaining in the former Soviet Union to come out of the shadows and practice their religion freely.

The writer, a rabbi, is a Chabad shliach in California, author of the upcoming book, Undaunted – the Life of Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneerson, The Sixth Lubavitcher Rebbe. His email is rabbi@ocjewish.com