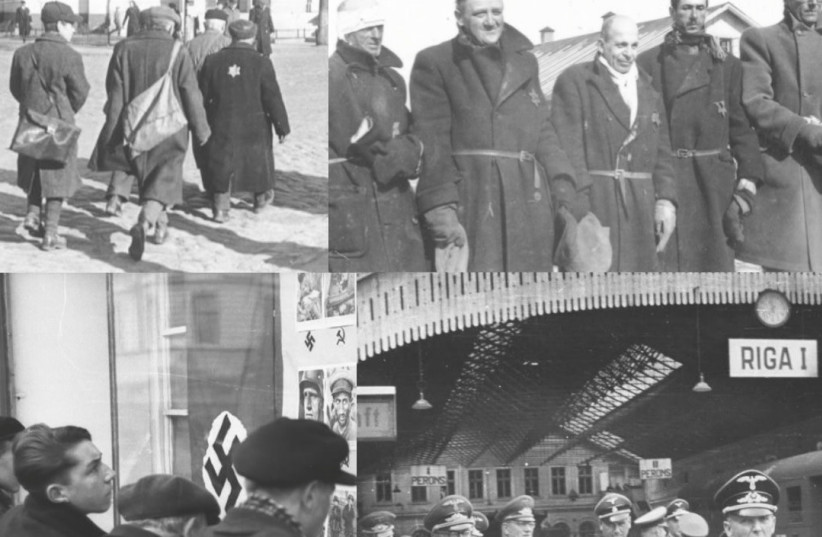

This summer we commemorated the 78th anniversary of the murder of the Jews of Hungary in the summer of 1944. Between May 15 and July 9 that year, 435,000 Jews from the provincial districts of Hungary were sent to their deaths, mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

I am not a historian, and do not presume to be one. But as a survivor, I feel a moral obligation to publicly discuss the forgotten mission of Joel Brand and his associates.

My brother Avram and I, born in the township of Karcag in central Hungary, are among the few hundred Jewish children from the Hungarian provinces who survived the deadly summer of 1944; none of the children who arrived at the same time at the gates of Auschwitz escaped.

The question that keeps running through my mind throughout the years is: To what extent do I owe my survival to the action of some brave people and their exceptional efforts during the Holocaust, and did these people receive the credit they deserve?

We survived because we happened to be on one of the six trains, out of 147, that left the ghettos of rural Hungary in 1944 that did not go to the extermination camps in Poland. These six trains, carrying around 15,000 Jews, were headed to the Strasshof transit camp in Austria and subsequently distributed in small working groups among the villages of Austria.

The formal explanation for this diversion from Auschwitz was that the Nazi regime complied with the request of Vienna’s district commander for working hands in agriculture during the summer of 1944.

Only 30% of the 15,000 deportees were fit for labor. The rest were children and seniors who had not been separated from their families. This was an indication that the Germans wished to preserve some sort of a family structure among a small group of Jews that could be used for negotiations with the West concerning their fate.

The fact of our survival indicates that despite the Nazi lies and their refusal to halt the mass murder – at a daily rate of about 12,000 victims every day – they were serious in their intention to spare the lives of some of the victims while negotiating with Jewish groups, with or without the backing of the Allied powers.

Blood for goods

The Nazi proposal presented by Adolf Eichmann to the Jewish Aid and Rescue Committee in Budapest was that in exchange for 10,000 trucks, the Germans would release one million Jews, mostly from Hungary, and allow them to go wherever they wanted. This ludicrous idea sounds unrealistic, but it reflects the Nazi perception according to which Jewish fortune had an unlimited influence on the West.

Brand, a Jewish-Hungarian businessman, managed to cultivate close relations with smugglers and German intelligence officers during the war and specialized, as a member of the Rescue Committee, in getting goods and refugees across the international borders of Hungary. He was selected by Eichmann, with the consent of the Budapest Rescue committee and the Jewish Council, to be flown to Istanbul and present the Nazi proposal to representatives of the Jewish Agency.

The mission, as we know, ultimately failed. But as long as it was ongoing, it kept protecting the lives of internees like us, who were destined to serve as subjects of possible usefulness for the Germans. The reasons for the failure of Brand’s mission were twofold: the objection of the Western powers to supply equipment of strategic value to the enemy, and the failure of the leadership of Hungarian Jewry to maintain close relations with the agency and other international Jewish organizations.

People tend to see Brand’s mission and the entire issue of “blood for goods” as a demeaning and humiliating Nazi term. This is the formal reason the West rejected the idea immediately, and the issue was not even brought to the attention of the Soviets.

The issue was also misunderstood by the Zionist leadership. Brand arrived in Istanbul on May 17, 1944, but was given a chance to meet Moshe Sharett only on June 10. Following that meeting, Sharett prepared a detailed report of Brand’s testimony, which described in great detail the horrors committed by the Nazis in Hungary, but did not mention the potential usefulness of such negotiations in gaining time to save lives. This indicates that the Zionist leadership did not understand this opportunity – that ongoing negotiations would have prevented, even for a while, the damage inflicted by the vicious Nazi death machine. Every delay during those days, when the Nazi empire was in demise, could potentially have saved thousands of lives daily.

The Zionist movement decided to act in full transparency with the British leadership, which ultimately led to the arrest of Brand in Aleppo, Syria, on his way to Palestine. This was the end of his attempt to slow the pace of the Nazi death machine.

Mistaken decisions

Choosing the agency’s branch in Istanbul, as it turned out, was a wrong decision. Although the Hungarian Rescue Committee had limited foreign relations, the Istanbul option was only one of them. Through these relations, the committee managed to smuggle funds into Hungary through diplomats of neutral countries such as Switzerland and Sweden. However, the agency’s Istanbul branch had neither the authority nor the ability to provide Brand with materials necessary to continue the negotiations with the Nazis in light of the information and opportunities presented by him.

However, history has shown us that at the same time an alternative option via Switzerland was also available. The American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, the largest Jewish humanitarian agency, appointed a Swiss citizen (Saly Mayer) as its representative in the negotiations with the Nazis. He was joined by Roswell McClelland, appointed by president Franklin Roosevelt as the US representative of the War Refugee Board in Switzerland.

On the Nazi side, the negotiations were closely followed by Hitler’s deputy Heinrich Himmler, whose representative to the negotiations in Switzerland was SS officer Kurt Becher, accompanied by the Budapest Rescue Committee envoy Rezso Kasztner (Rudolf Israel Kastner), a close associate of Brand.

While these negotiations were ongoing in the last months of the war, documents show specific dates on which Himmler ordered halting the operation of all gas chambers and stopping the transport of the Jews of Budapest to Auschwitz.

Although the Nazi machine of extermination did not stop during the summer of 1944, some achievements were in all likelihood the outcome of the efforts of the Rescue Committee in Budapest: the Kastner train, carrying 1,684 Jews, who managed to escape to Switzerland despite a long delay in Bergen-Belsen, and the 15,000 Hungarian Jews of the Strasshof transport, the majority of whom survived the war as potential merchandise for Nazi aspirations of “blood for goods” which never materialized.

Epilogue

It would be unjust to criticize decision-makers for not understanding the significance of developments in real-time, in the critical months of May to July of 1944, during which Hungarian Jews were being murdered at a rate of 12,000 persons per day.

But 80 years later, we may state that Brand and his associates from the Budapest Rescue Committee saw the opportunity missed by the members of the agency to save Jews by maintaining negotiations. In late 1944 the imminent collapse of the Nazi empire was realized by all, and the negotiations via the Budapest Rescue Committee were a feeble attempt by the Nazis to improve their postwar positions by contacting world Jewry, which, according to Nazi dogma, had an unlimited influence on the West.

In history, it is not uncommon to speculate on things that did not happen. We don’t know whether more lives could have been saved if the Zionist leadership had taken Brand seriously and lent him, early on, a helping hand in his attempts to maintain the negotiations in return for halting the death trains to Auschwitz.

But I know that my life and the lives of my entire family were saved thanks to the Strasshof transport. The days in the forced labor camp were hard and full of uncertainty, but in the spring of 1945, Vienna was liberated by the Russian army, allowing us to start our long walk back to Hungary. A couple of years later we reunited with my father, who had served in the Hungarian forced labor service, allowing us to depart to Israel and start restoring our lives.

The purpose of this article is to express my appreciation to Joel Brand, whose failed mission was lost in history but meant everything to me and my family, and to Rezso Kasztner for his role in the Strasshof saga and many other achievements.

I would like to thank my grandson Udi Shaham-Maymon, the night news editor of The Jerusalem Post, for his important comments and insights, which helped construct this article.

The writer, a Strasshof survivor, is a leading hematologist who served as head of Internal Medicine at Shaare Zedek Medical Center between 1980 and 2003. He also served as the Health Ministry’s ombudsman for medical affairs between 2009 and 2017.