| More about: | Yitzhak Shamir, Yasser Arafat, Hussein of Jordan, Ariel Sharon |

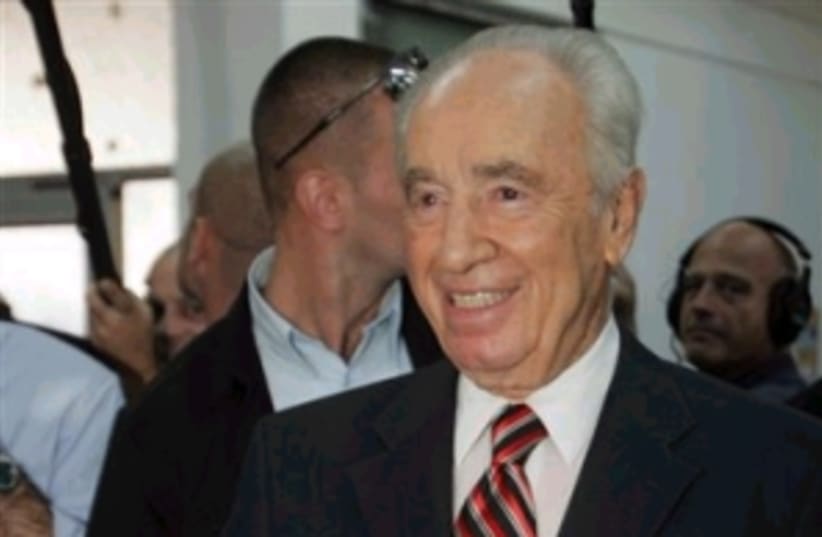

End of the Peres era

Leaving the Labor Party signals the end of an era, even if he still returns as a minister.

| More about: | Yitzhak Shamir, Yasser Arafat, Hussein of Jordan, Ariel Sharon |