Sanders may play down Judaism, but he played big role in Hannukah case

As mayor of Burlington, Sanders agreed to allow a public menorah to be displayed on municipal grounds, a move that eventually was contested in court.

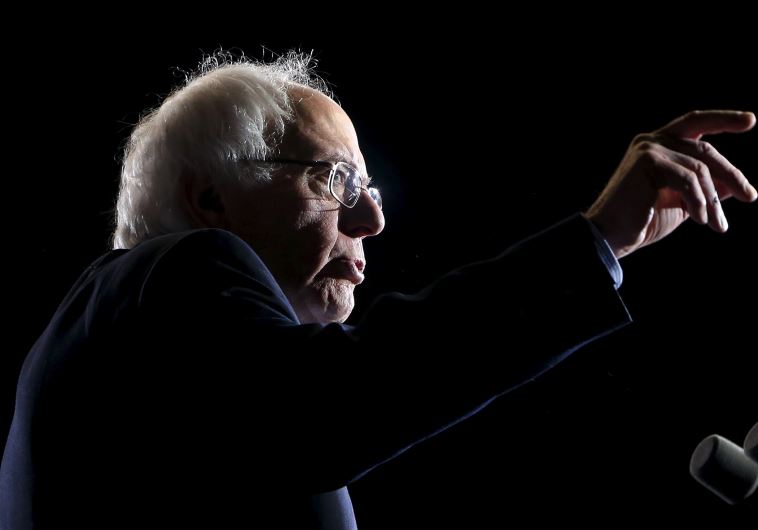

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) campaigns in ClevelandUpdated:

Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) campaigns in ClevelandUpdated: