I take loans from my boss and my father-in-law

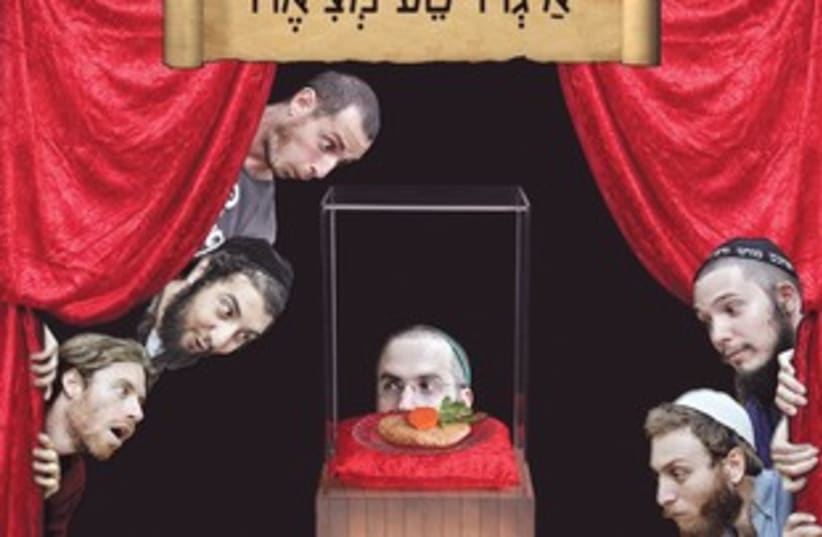

My wife eats gefilte fish at the neighbor’s wife

And I travel to Uman with the rest of the neighborhood”The duality of the deadpan delivery on one hand, and the total acceptance of the lifestyle they’re singing about on the other, contributes to the sense of multiple personalities emanating from the six-piece band, which has just released its second album, Hatnua L’shichrur Hameyutar (The Movement for the Liberation of the Extraneous). Which isn’t surprising, considering that most of the band consists of ba’alei tshuva members – musicians who found religion early in their careers and didn’t want to give up the music they love. “We’re all sort of lighthearted,” said the band’s guitarist/singer and co-founder Nadav Bachar. “There’s a midrash that a great rabbi, before teaching his students, would tell a joke and everyone would laugh and then get down to studying. If I want to sing about things I’ve learned, I can use humor and it comes across in a little easier fashion. The goal is to get to people and touch their hearts.”Bachar grew up in Hadera, the product of a secular education. He’s been playing professionally for more than a decade and was a member of a progressive rock-influenced band Parva Hama (Hot Fur), which released an album to minor acclaim in the late 1990s. From there, he collaborated with known personalities such as Tomer Yosef of the Balkan Beat Box, where he began to learn some of the eclecticism that he brought to A Groyse Metsie (Yiddish slang for ‘a real find’). He had already been playing with some of his future bandmates in a secular environment when he began getting closer to his Jewish roots through an affiliation with Chabad.“I stopped performing for about a year while I learned,” said Bachar. “I realized that before I became religious, I always had a problem with music – I felt that I was enslaved by it. All the practicing and performing, it begins to weigh on your conscience: ‘I’m not practicing enough. I’m not playing enough.’ Everything in your life begins to revolve around music, and I arrived at a place where I didn’t want it anymore, I wanted to be liberated from it. I tried to find where my place was, and after a period of time of returning to Judaism I was able to return to music, but I was able to approach it in a healthier way,” he said.Coincidentally, other members of the band also began the path to an observant life around the same time, including violinist Oren Tzur, Feldman and keyboardist David Ada, resulting in A Groyse Metsie’s including a microcosm of Israeli society – knitted kippot, Chabad, Breslov and even a secular kibbutznik.“Eyal [Nissenboim] and Ofer Eshed, our bass player and drummer, aren’t religious in a traditional sense, but they have a strong connection to spirituality. It interests them, but there hasn’t been any outward moves by them,” said Bachar, adding that he saw no problem with not all the band following the same spiritual tune.“I don’t think it matters when you’re playing together. We’re all individuals. There are evil people among the haredim, and there are tzadikim among the secular,” he said. “There’s everything everywhere. A person is just a person.”When the friends began to get together to jam, the unique combination of personalities and crisscrossing lifestyles led to their first spiritually inflected album, released in 2006.“It wasn’t very organized, it was mostly based on the jams we were having,” said Bachar.FOUR YEARS later, their new album is organized, indeed. Produced by Hadag Nahash’s Dudush Kalmas, the music careens from fat hip-hop grooves and distorted guitar solos to semitraditional klezmer and reggae, all of it sounding utterly contemporary. For Bachar, it’s a journey to take the profane and create something meaningful.“The material on the album is an effort at taking the music that is associated with negative elements like sex and partying and to make it holy. Our desire was to take the different styles we all bring to the table and bring them to a higher place,” said Bachar.“There’s something Jewish or something spiritual in every song that keeps it from being ordinary, and I hope we succeed that when you hear a song or see a clip, it give a feeling that you’ve gotten something of quality out of it.”Bachar also hopes that the example the band provides will help bridge the secular-religious gap that’s prevalent in Israeli society.And as someone’s who been on both divides of that gap, he’s in a position to see things more clear-eyed than most.“I hope people can start looking at each other differently. I look at everyone as people – not as Chabad or Sephardi or by what they wear and their outer markings. In a natural way, it’s supposed to be like that,” he said.While the band has developed a loyal following in the religious community, Bachar hopes that the new album and upcoming shows the band is performing will bring in a larger secular audience who are ready to party in the style of A Groyse Metsie.“We’ve had a lot of fun shows in Jerusalem. It’s mostly a religious audience, but there are some non-religious who are coming now. Tel Aviv is tougher because we’re still not that known there,” he said.For a real find like A Groyse Metsie, that anonymity won’t last for long.