Jerusalem state of mind

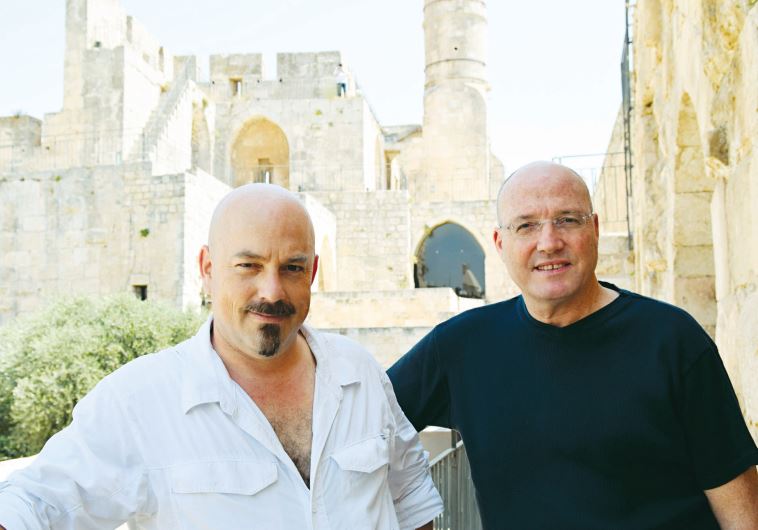

Bezalel greats Ezri Tarazi and Haim Parnas show off their unconventional housewares at the Tower of David.

Haim Parnas and Ezri Taraza outside their exhibit at the Tower of David museum in Jerusalem.(photo credit: HAMUTAL WACHTAL)

Haim Parnas and Ezri Taraza outside their exhibit at the Tower of David museum in Jerusalem.(photo credit: HAMUTAL WACHTAL)