If then anyone transgresses the prohibition against you, transgress likewise against him (Koran 2: 194).

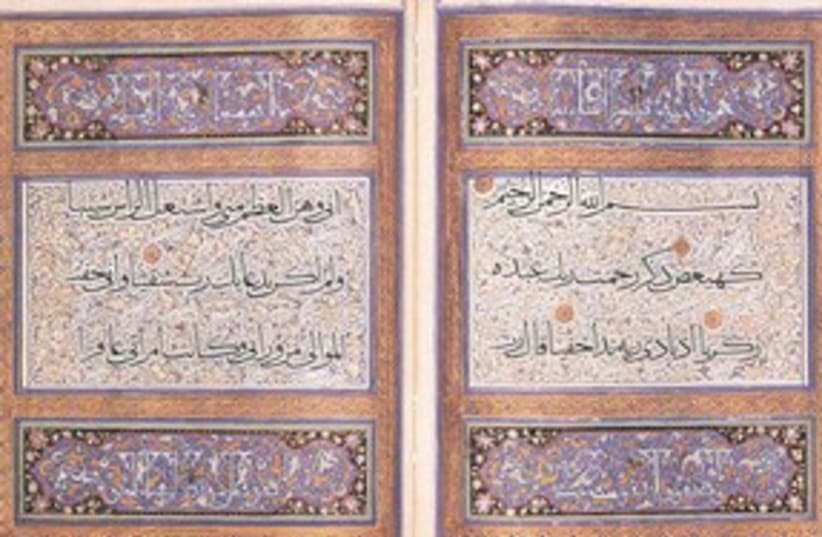

Palestinians and other Muslims can use such text to justify their violent resistance to the Israeli occupation. This means that peace will only be possible with an end to the Israeli occupation. According to Islamic teachings, if Muslims learn that their enemy desires peace and is willing to cease all forms of aggression, Islam commands Muslims to agree to their enemy's request.Islamist extremists might find it comforting to invoke Koranic verses to justify acts of terrorism against the Jews. But committing acts of terrorism in the name of Islam – most recently the random killings in Toulouse – is actually an insult to the religion, which consider all life forms sacred and condemns killing innocent people, even in times of war.On the Jewish side, the continued Israeli occupation and the subjugation of the Palestinians to daily indignities does little to enhance the image of Jewish teachings. Religious belief, be it Jewish, Christian or Muslim, was not meant to provide cover for injustice. On the contrary, the three monolithic religions strongly advocate brotherhood, justice and peace.There are many skeptical Israelis who understandably do not believe that an Islamic world mired in internal conflict would accept Israel as a Jewish state. The Israelis point to Muslims butchering one another in the Sudan, Iraq, Libya and now Syria as evidence that violence is inherent to the religion and culture.I do not subscribe to this proposition for four reasons:the Koran's teachings consistently point to the contrary;neither violence nor extremism is exclusively Muslim (note European history from the time of the Inquisition to date);time and circumstances have changed as the Arab youth have awakened and now see despotic regimes rather than Israel as the culprit of their socio-economic and political plight; andthe Muslim world has, with the exception of a tiny fraction of Islamist militants, come to terms with the unequivocal reality of Israel.

Conversely, Israel must come to terms with the changing political wind by removing the stigma of occupation. The country is powerful enough to take the calculated risk of testing the Arab states' protestation that they will only seek peace if a mutually acceptable solution is found to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.Indeed, it flies in the face of reality to portray the relationship between Islamic-leaning Arab states and Israel as irreconcilable. Israel should remember that it was Saudi Arabia, one of the most conservative Islamic countries, that advanced the Arab Peace Initiative in 2002, and it is Israel that still, a decade later, refuses to embrace the proposal.To disabuse their respective religions' false perceptions, Jewish and Muslim scholars should engage in an open dialogue. They can use modern communication tools to discuss topics such as the future of Jerusalem and use religious teachings to make their case.Over time this will provide policy makers, be they religious or secular, the political cover they need to pursue reconciliation. The question now is, how much more anguish and uncertainty will Israel and the Islamic Arab endure before deciding it's time to talk religion?The writer is a professor of international relations at the Center for Global Affairs at NYU. He teaches courses on international negotiation and Middle Eastern studies.