Bauing out with style

The exhibition includes some new works that feed of the same thematic early 20th-century sensibilities but with a contemporary twist...

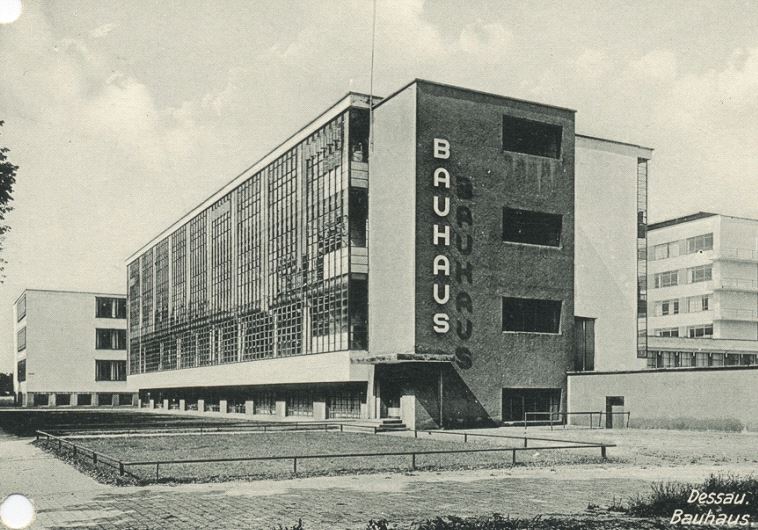

The mural workshop, Bauhaus Dessau, 1926(photo credit: BAUHAUS-UNIVERSITÄT WEIMAR/ARCHIVE DER MODERNE)

The mural workshop, Bauhaus Dessau, 1926(photo credit: BAUHAUS-UNIVERSITÄT WEIMAR/ARCHIVE DER MODERNE)