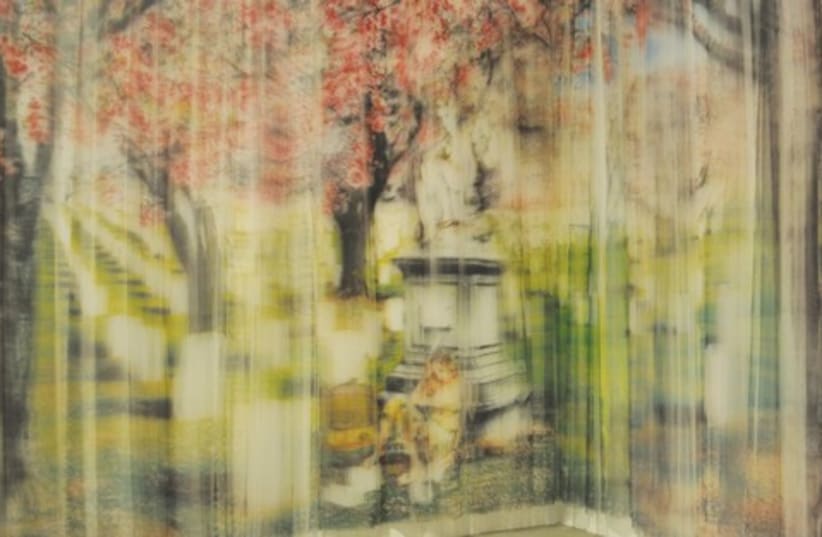

Despite the title, the work is anything but bleak. The hangings present a panoramic vista, resembling an arcadian scene of classical statues, a lake and fields of white graves, all set against vibrantly colored, rose-blossomed trees.A girl sits beneath one of the statues, a birdcage by her side.The scene is beautifully rendered, the colors as vivid as those of Matisse or the Impressionists. Yet as with the other settings it is tinged with melancholy; the gravestones cast no shadow on such a glorious scene; rather, it is the realization on our part that this is simply too lovely, too unreal and so removed from our present-day life.The four gallery spaces given over to these hangings can only be fully taken in by being present in the space – even photographic reproductions do not capture their effect. This is possibly because each work essentially creates a setting on a four-walled space, but also because of Patkin’s technique, partly achieved through his use of tulle, of never fully revealing his characters, who appear as apparitions in ill-defined landscapes.The Veiled Suite is the high point of the exhibition, but there are other works on display that, taken as a whole, contribute to a show that, at times, seems like a paean to a distant past, or at least to have left the 21st century behind.The soft folds of a porcelain sculpture of the Virgin Mary are offset by a striking, jagged glass sculpture titled The Messiah’s GlAss. Portraits of family members, ballet dancers and a series of paintings influenced by Middle Eastern mosaic patterns, all continue the historical theme, which is at times nostalgic, but not sentimental.The exhibition closes on December 1.

Tribute to a distant past

The 4 gallery spaces dedicated to Izhar Patkin’s new exhibition can only be fully taken in by being present in the space.

Despite the title, the work is anything but bleak. The hangings present a panoramic vista, resembling an arcadian scene of classical statues, a lake and fields of white graves, all set against vibrantly colored, rose-blossomed trees.A girl sits beneath one of the statues, a birdcage by her side.The scene is beautifully rendered, the colors as vivid as those of Matisse or the Impressionists. Yet as with the other settings it is tinged with melancholy; the gravestones cast no shadow on such a glorious scene; rather, it is the realization on our part that this is simply too lovely, too unreal and so removed from our present-day life.The four gallery spaces given over to these hangings can only be fully taken in by being present in the space – even photographic reproductions do not capture their effect. This is possibly because each work essentially creates a setting on a four-walled space, but also because of Patkin’s technique, partly achieved through his use of tulle, of never fully revealing his characters, who appear as apparitions in ill-defined landscapes.The Veiled Suite is the high point of the exhibition, but there are other works on display that, taken as a whole, contribute to a show that, at times, seems like a paean to a distant past, or at least to have left the 21st century behind.The soft folds of a porcelain sculpture of the Virgin Mary are offset by a striking, jagged glass sculpture titled The Messiah’s GlAss. Portraits of family members, ballet dancers and a series of paintings influenced by Middle Eastern mosaic patterns, all continue the historical theme, which is at times nostalgic, but not sentimental.The exhibition closes on December 1.