Know Comment: Remembering Rabin and Shamir, correctly

Rabin’s true legacy is Israel’s struggle for secure and defensible borders and a unified Jerusalem, and great wariness of Palestinian statehood.

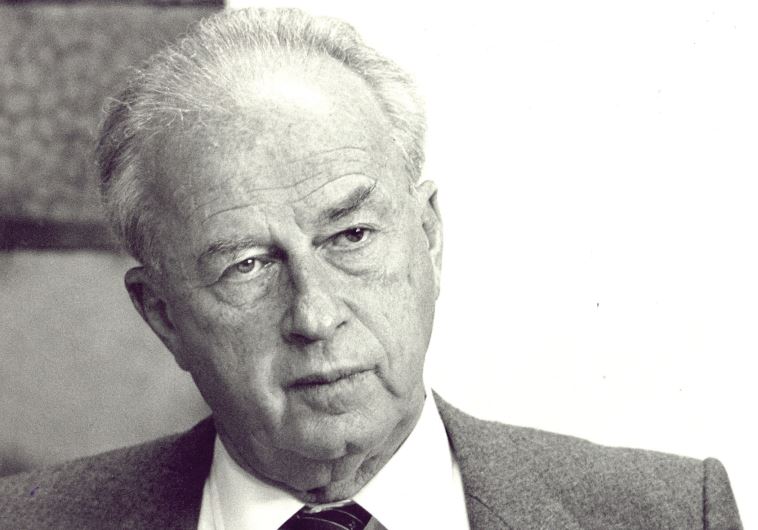

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)

Yitzhak Rabin in 1985, then defense minister(photo credit: DAVID BRAUNER)