This Passover, on the 18th of Nissan, we mark the 30th yahrzeit of Rabbi Joseph B. (Yosef Dov) Soloveitchik – "the Rav" as he is known to his myriad of disciples and the generations of disciples following them.

Though the youngest people who were of sufficient merit to study with him directly are now in their sixties, his legacy is stronger than ever. Dozens of books filled with his Torah have been published posthumously, outweighing even what he published in his lifetime. We now have access to more of the Rav’s Torah than ever before, comprising a significant part of the Rav’s legacy. However, I believe that his personal legacy – who he was as a person – is no less crucial.

The Rav was a man of astounding integrity. I vividly recall occasions when the Rav, after grappling with weighty questions, chose to follow the lonely path that he believed was correct – even at the expense of his strong commitments to his family’s traditions, even if it meant going against the consensus of other Torah giants, and paying a personal price for those choices.

A shift of allegiance

One such departure surrounded his attitudes toward Zionism and the State of Israel. In the early 1940s, the Rav shifted his allegiance from Agudat Israel to Mizrachi. By the mid-1950s, he had emerged as an important Diaspora spokesman for the State of Israel, interceding with other faith leaders on the fledgling state’s behalf without hesitation.

Yet even as he took up this mantle, he could not forget that it diverged from his roots. In a series of lectures that he delivered on behalf of the Religious Zionists of America in the 1960s (published in English as The Rav Speaks), he often returned to the theme of charting a different course from that of his family and teachers.

I remember a playful conversation that the Rav related between him and then-prime minister Menachem Begin. Begin came from the city of Brest-Litovsk, known in Yiddish as Brisk. The Rav’s grandfather, the famed Rav Chayim, was the city’s rabbi, and Begin’s father Wolf-Dov was gabbai of the city’s main synagogue. The two men had opposing views of the Zionist movement and, according to legend, Wolf-Dov Begin defied R. Chayim by arranging a eulogy upon the death of Theodor Herzl. Prime minister Begin pointed out to the Rav the irony of R. Chayim’s grandson becoming the preeminent spokesman for Religious Zionism in the Diaspora.

THE RAV’S integrity extended to the primary arena of his work: the classroom. In the Rav’s Talmud class, what mattered was the truth; not a student’s age, experience, or family name. At times, the Rav would dismiss a veteran scholar’s thesis in favor of a young student’s suggestion. I will never forget the time the Rav, after a two-and-a-half-hour Talmud shiur, asked me to bring him to a student who had asked a certain question. The Rav told him, “You were right and I was wrong. Tomorrow we will restudy the topic based on the question you raised.” Such was Rav Soloveitchik’s intellectual honesty.

That same educational integrity motivated the Rav’s view that girls and women should be afforded opportunities to study the Oral Torah, including the Talmud – despite a long record of rabbinic opposition. Thus, when he and his wife, Tonya, established the Maimonides School in the Boston area, he insisted that all students, male and female, study the same curriculum, which included these subjects. It was inconceivable for him that women should be encouraged to achieve the highest level of scholarship in all fields of knowledge except Talmud.

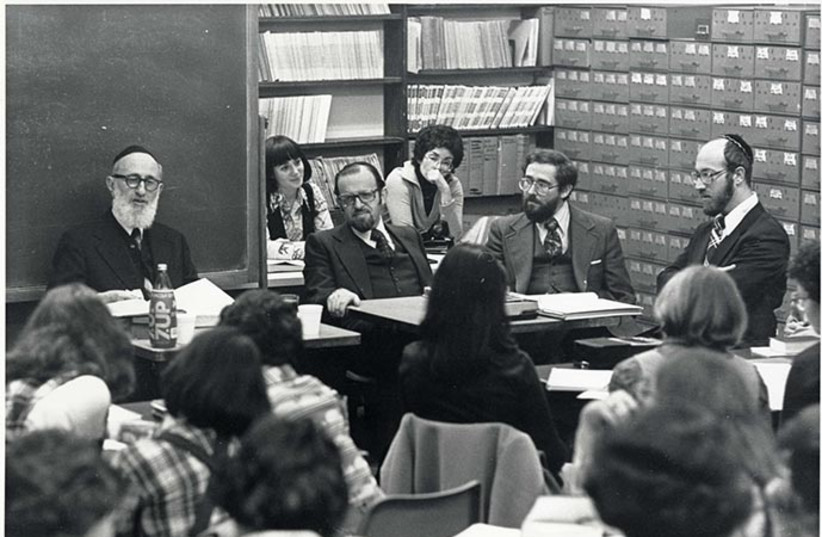

In 1977, the Rav gave a Talmud shiur at Stern College for Women. He related to me that he gave that lecture to ensure that no one could claim that Talmud was taught at Stern without his approval. He wanted the initiative to have his public imprimatur and emphasize the importance he ascribed to Torah and Talmud study by women.

It is no coincidence that now, 45 years later, women studying Torah has become the norm in many Orthodox communities, and many of the foremost institutions of high-level women’s Torah study in Israel and North America were founded and are nurtured by students of Rav Soloveitchik, and their students after them. His commitment to this project has yielded productive positive dividends.

Yet these two stands had their isolating consequences. When his friend and colleague Rav Aharon Kotler, the head of Beth Midrash Govoha in Lakewood, New Jersey, passed away, the Rav went to the funeral with a prepared eulogy for the man he worked with for decades to strengthen Jewish education in America and Israel. However, he was not asked to speak due to his advocacy of Talmud study for women and Zionism.

A teacher through and through

INTEGRITY AND intellectual honesty were far from the only qualities that the Rav exemplified as a teacher. Viewing himself first and foremost as a teacher, his clarity and his complete absorption in the subject matter made his Talmud shiurim exciting, attracting a variety of thinkers and scholars from across the globe, young and old, who hung on every word he spoke. When he presented the view of one of the great Talmud commentators, we felt as though they were present in the room. Rashi and Rif, Rambam and Ra’avad, Rabbenu Tam and Rashba were there with us in Furst Hall 401 when the Rav gave his shiur.

The Rav was a demanding teacher. His shiurim could last close to three hours, and he expected preparedness, precision, and clear understanding from his students.

Outside the classroom, however, his demeanor was welcoming, gentle, and kind. I recall how often people left the Rav’s apartment with a sense of comfort, either because the Rav had a solution to their problems or simply because he had listened so intently. When the Rav heard of a fellow human challenge, be it a head of state or a simple Jew, he was so empathetic that you could see the pain and anguish on his face and frail body. It would be harder for him to walk and eat. He was happy when he could marshal his prodigious Torah knowledge and halachic arsenal to help people, and he was pained – to the point of losing sleep – when he could not.

Today, it is common for different views of the Torah to become points of friction between camps, so we have much to learn from how the Rav and his friends interacted. Although they did not agree on several major issues, they respected one another and treated each other with the greatest reverence. Every time a new book was published by Chabad, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, a friend of the Rav from their time together in Berlin, would send a copy, often with a personal inscription. Rav Moshe Feinstein, Rav Yaakov Yitzchak Ruderman, and the Rav would call each other before every holiday.

Rav Moshe passed away on Ta’anit Esther of 1986. At the time, the Rav was unwell, so his family asked us that he not be told of his friend’s death. We intercepted the New York Times normally delivered to his apartment each morning, and his radio suddenly “malfunctioned.” We thought we had succeeded in shielding the Rav from the news. But prior to Pesach, the Rav summoned me from the beit midrash (study hall) to drive him to LaGuardia Airport for his flight to Boston. As we drove, the Rav asked me why I hadn’t informed him of Rav Moshe’s passing.

I was astounded. After several moments, I explained his family’s request and concern for his health. I then turned to him and asked how he found out. He replied: “Every chag either I call Rav Moshe or he calls me. This Pesach it was his turn to call me. There can only be one reason why he did not call…”

On the occasion of the Rav’s 30th yahrzeit, let us recommit ourselves to his Torah and his character.

The writer, a rabbi, is president and rosh hayeshiva of the Ohr Torah Stone international network of 30 educational, outreach, leadership and social action programs. He served as student assistant to Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik from 1982-1985.