A new study found that the alarming rate at which the massive Thwaites Glacier in Antarctica, about the size of the US state of Florida, is melting, can be predicted using a combination of computer models and physical data.

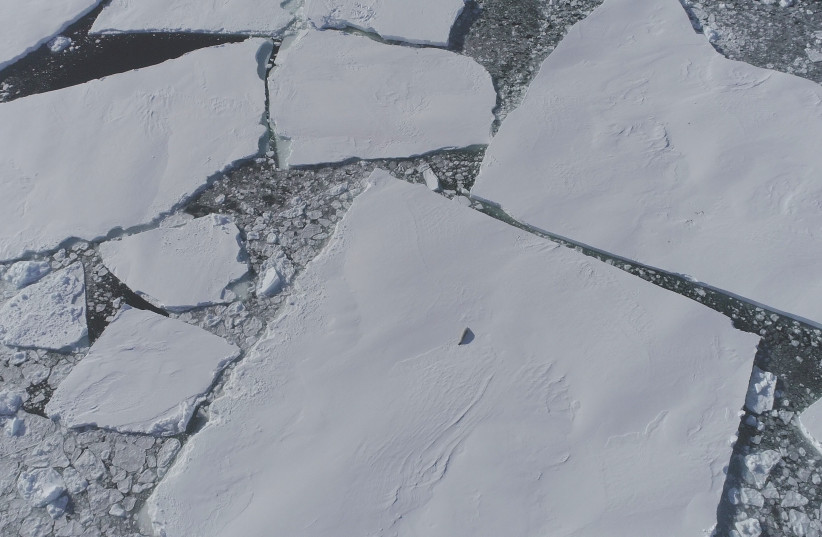

The peer-reviewed study, published in the scientific journal Nature on Monday, mapped a critical area of the ocean floor in front of the glacier in order to determine how much it has thawed in the past.

The glacier is already known to be thawing at a rapid pace, but it is not known precisely how fast it will melt or how much ice will fall into the ocean.

What is a glacier?

It is estimated that the complete loss of the glacier and surrounding ice basins would raise the sea level from three to 10 feet.

In the study, researchers captured images of geologic features that were not yet previously known to have existed, enabling the projection of future changes in the glacier.

Analyzing the past

“The images Ran collected give us vital insights into the processes happening at the critical junction between the glacier and the ocean today.”

Anna Wåhlin, physical oceanographer, University of Gothenburg who operated Rán

Why is it called the doomsday glacier and why is it melting?

The rate at which the Thwaites Glacier, also known as the doomsday glacier, Antarctica's second-largest marine ice stream, is melting is a major uncertainty, according to the study.

“The glacier's bed deepens upstream to > 2 km below sea level and warm, dense, deep water delivers heat to the present-day ice-shelf cavity, melting its ice shelves from below,” the study noted, adding that these conditions render the glacier vulnerable to runaway retreat.

The images taken by the researchers include 160 parallel ridges that formed as the edge of the glacier bobbed up and down with the tides.

What happens if the doomsday glacier melts?

In order to document how much the glacier retreated in the past, the researchers analyzed these formations 700 meters underwater, using computer models to predict the tidal cycles. They found that one ridge had been formed per day.

Furthermore, the researchers found, at one point in the past 200 years, over a period of fewer than six months, the edge of the glacier retreated by over 2.1 km per year, two times faster than the rate recorded by satellites from 2011-2019.

Rán the robot

In order to capture the images and supporting data, the researchers used a robotic vehicle equipped with sensors.

How big is the doomsday glacier?

The robot, called “Rán,” mapped an area of the seafloor in front of the glacier measuring about the size of Houston, Texas, allowing scientists to access the glacier for the first time ever.

“This was a pioneering study of the ocean floor, made possible by recent technological advancements in autonomous ocean mapping and a bold decision by the Wallenberg foundation to invest into this research infrastructure,” said Anna Wåhlin, an oceanographer from the University of Gothenburg who operated Rán.

“The images Ran collected give us vital insights into the processes happening at the critical junction between the glacier and the ocean today.“

The researchers added that “our results suggest that sustained pulses of very rapid retreat have occurred at Thwaites Glacier in the last two centuries. Similar rapid retreat pulses are likely to occur in the near future when the grounding zone migrates back off stabilizing high points on the sea floor.“

The Environment and Climate Change portal is produced in cooperation with the Goldman Sonnenfeldt School of Sustainability and Climate Change at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. The Jerusalem Post maintains all editorial decisions related to the content.