This past June,award ceremony of the EMET Prize, also known as the Israeli Nobel Prize, was held in Jerusalem. The award was presented to six winners for academic and professional achievements that have made significant contributions to Israeli life in three categories: social sciences, life sciences and the humanities. In this article, we meet the two distinguished winners in the humanities, who deal with one of the most fascinating subjects in the genre – archaeology – the field that connects to the present and projects to the future.

“I never dreamed of a career in the field of Chinese and Mongolian research,” says Prof. Gideon Shelach-Lavi of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who received the EMET Prize. Shelach-Lavi conducted extensive archaeological research in northern China and Mongolia and contributed to Israeli academic and archaeological knowledge by studying cultures and regions that were foreign to Israeli research.

“As a child from Kibbutz Mishmar Ha’emek, I collected coins and had a basic interest in the field. I then studied archaeology at the Hebrew University and wanted to expand my knowledge, so I took courses in Asian studies, and from there, everything followed.”

In the early 1990s, when China was still closed to Israel, Shelach-Lavi took part in a pioneering delegation of student exchanges. “I studied Chinese and later received my Ph.D. in the US on the archaeology of China. I found that archaeological research in a distant and lesser-known place provides more freedom to deal with big questions.”

Shelach-Lavi discussed his recent research on the beginning of agriculture and the transition of humans from hunter-gatherers to farmers. “The transition to a society of permanent residents and farmers is perhaps the biggest change that has happened to humankind. On an archaeological scale, this is a change that took place over thousands of years that we have not fully solved.” Currently, he focuses on research in Mongolia concerning a large network of 4,000-km. walls known as the “Genghis Khan” Walls, built in the 11th century.

Archaeology outside of Israel, and particularly in China, is less biblical. Is it easier to deal with questions that are further removed from ourselves?

In China and many other places, archaeology also has political and social contexts. There is something about archaeology that makes people associate it with national questions and questions of identity. I come to China in a ‘cleaner’ way because I’m not part of the culture, but I always work with local archaeologists. For me, it makes it possible to think about things more openly – the big questions, what happened, what people did in the past. I am interested in how people lived, what they did and how they caused great changes.

How did the Chinese and Mongols get an Israeli archaeologist?

I have been working almost continuously in China since 1994. Israelis have an advantage because we are not part of the issues that concern them. The people with whom I collaborate like the fact that foreign professionals bring new ideas and technologies. Archaeology is teamwork that combines different disciplines. We use not only dating but also studies on botany, zoology, geology and chemistry. In recent years, we have been able to learn what people ate, and understand their DNA from chemical remnants. All of my research has been conducted with multidisciplinary and multinational groups.

How much fieldwork is required in research?

People don’t realize that for every month you work, a huge amount of data is collected. This is part of the problem – archaeologists are tempted to dig endlessly, and then for 20-30 years, the reports do not come out because there is a huge amount of data. I balance things by working for a month – this year a little more because of the coronavirus – and then process the data. Most of my research was more regional – to understand the space where humans established their communities and the relationship between location and environmental conditions. It’s less about digging and taking out pottery and more about surveying the surface and targeted excavations.

Archaeology is essentially history. Is there an added value in seeing how it affects the present and perhaps the future?

Archaeology is history, and in Israel it is very much related to history, but it also has anthropology. In the US, for example, archaeology is part of the Department of Anthropology and not History because we are trying to understand how people behave – what they do and their daily lives, which we do not often see in history. A major part of it is to understand human life, the changes that are taking place, the society and the mechanisms that activate it.

How relevant are your research topics to Israel?

My general approach is to understand human behavior throughout the ages, and this is also relevant to things that occur here. For example, the development of agriculture is a process that happened more or less simultaneously in our region as well. It is fascinating to compare the processes and where they led here and in China.

Were you surprised to receive the prize?

It’s a great tribute, and I thank my colleagues who nominated me and supported me. I was surprised because the subject was archaeology, and I thought they wouldn’t award the prize to someone who doesn’t work in Israel. I think it’s important that archaeology be perceived as something that is not only local but universal. We need to look at other cultures to learn other things about ourselves. I always tell my students that we must know about the other and understand that we are not the center of the world. At the end of the day, we are all human beings, and this allows for a broader view of ourselves.

Not just students with shovels

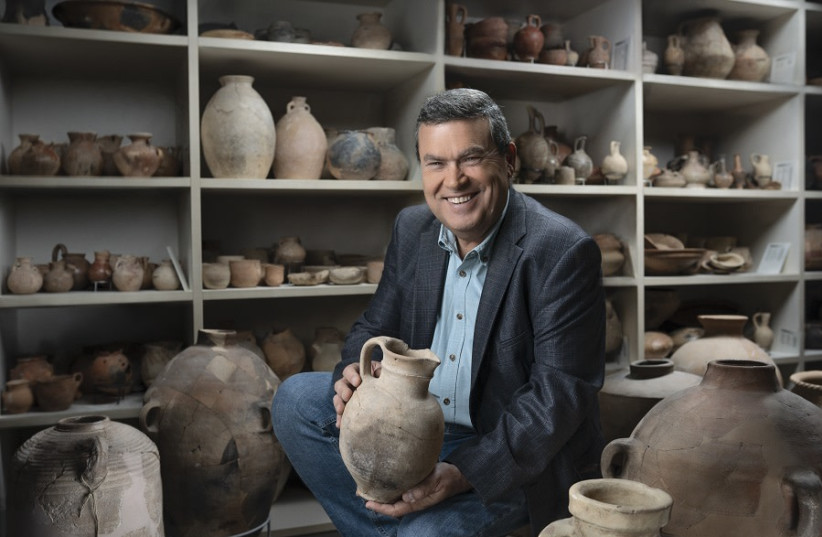

“The limitation of archaeology is that you dig where you know there is a wall, or think there is a gate or houses, and sometimes you hit, and sometimes you miss,” says Prof. Oded Lipschits of Tel Aviv University, who received the EMET Prize in the field of humanities for his contributions to archaeology. Lipschits is internationally known for researching the history and archaeology of the Land of Israel during the first millennium BCE at a huge excavation project currently underway at Tel Azeka. He has also served as head of the Institute of Archaeology for the past 11 years.

“Archaeology today is based on advanced technologies. It’s no longer just students with shovels. We arrive with 20 experts, each an expert in different fields, to assist us.”

The history comes out, and suddenly you understand and discover things you never knew. How do you know what you’re looking for?

When you dig at a biblical site, it’s a site where people lived. In what periods did they live? At Tel Azeka, for example, we knew the periods, but there is an endless number of artifacts. You are digging in a place where people lived, layer upon layer. The most recent layer is on the top, and the earliest is at the bottom, and they remove it like layers of cream on a cake.

Being an archaeologist is like being the conductor of an orchestra. I have 20 ‘musicians’ from different fields, and you have to coordinate between them. The main problem in archaeology is when there were long periods when people lived in peace. It’s not pleasant to say, but it is very bad for archaeologists because nothing was found. On the other hand, if there was destruction, archaeology is glad that it preserved a certain situation beneath it.

Lipschits discusses the destruction and discoveries in the Canaanite city of Azeka after two severe destructions, which left amazing findings in the area of archaeology, and DNA, as well as shocking discoveries on a human level, including human remains. “Sometimes destruction reveals to us things that are very difficult to see, such as walls that collapsed on people and remained in an existing state. We examine the teeth and the DNA, and with the help of metallic identification known mainly from wisdom teeth, we can learn where the people came from. We also find pottery at the sites of destruction. In the case of Tel Azeka, we found a huge cache of jewelry wrapped in linen cloth that has survived for thousands of years. You see and connect it to the existing history.”

Have there been cases of incompatibility between the biblical story and the findings on the ground?

“Of course. The accepted concept was that there was the First Temple, followed by the Babylonian exile and the Second Temple period. Over the years, biblical scholars understood that the captives of Zion who returned from the Babylonian exile were a very small minority. They were comfortable shaping this concept because it was part of their conception of ownership of the land. In my research, I discovered that there are cases in which the biblical period should be treated differently.”

Lipschits discovered in his research that for 600 years, the great empires ruled the land. After the Hasmonean revolt, there was an independent Jewish rule for 70 years, and then the Romans came. “Between the First and Second Temples, there are almost no periods of Jewish independence in the land. Most of the time when Jews lived in the country, they were under the rule of empires that ruled it.”

This is the period in which the Bible was written and Judaism was shaped, in which everything we are today evolved

“I’m currently recording a series of podcasts called The Untold Story of the Kingdom of Judah, and I’ll say this – ‘This is what the Jerusalem Bible writers told us, and this story doesn’t make sense.’ This is the stage where I show that there are many gaps in this story, and it is clear that it was written at a very late stage to shape history as the Jerusalemites wanted, usually for themselves and their audience.”

They didn’t want to show it to us because…

Exactly. And the more interesting thing is, what did they not tell us? They didn’t tell us about things they didn’t know, far from Jerusalem, things that had happened earlier or that didn’t fit their agenda. We discovered, for example, a temple that corresponded to the dimensions of Solomon’s Temple that existed under the bridge at Motza. This temple was never mentioned in the Bible, nor was the governmental center in the Ramat Rachel area.

The Bible does not mention them, and we don’t know why, because those who were in Jerusalem at that time knew about the existence of the temple, and the ritual remains found there will attest to this. When the Bible ignores, archaeology ultimately tells this story.

The beauty of this work is that you never know what surprises will come, and sometimes you have to change the archaeological story you have already found and, subsequently, the historical and biblical story.

How does it feel to receive recognition after such strenuous work?

It’s a big surprise for me because I’ve never worked for awards, and those who have received these awards are very respected people, some of whom I’ve admired for many years. As with any job, I came home from the ceremony and continued to write the article, checking 70 student exams. So the hard work continues as usual.

Translated by Alan Rosenbaum.

This article was written in cooperation with the EMET Prize.