On November 29, 1947, when the United Nations General Assembly resolved to partition Mandatory Palestine into two states – one Jewish and one Arab – slightly more than a million people were assigned to live in the Jewish state. They were split between 630,000 Jews and about 400,000 non-Jews, allowing a modest Jewish majority of 63 percent.

One of the most dramatic consequences of the War of Independence was the exodus, whether voluntarily or forced, of large numbers of Arabs, including some from territories newly annexed to the State of Israel in the Galilee, the south, and western Jerusalem. This placed the demographic balance in late 1948 on more solid grounds in terms of the Jewish majority – 717,000 Jews vs. 156,000 non-Jews, or 82 percent.

Over time, the population of Israel has increased to just over two million in 1960, about four million in 1980, nearly six and a half million at the turn of the current century, and nine and a half million today. This tenfold increase within 75 years is paralleled in any other western country. For example, the population of Australia grew threefold during this period, that of the United States twice as much, and those of France and England by one and a half times each.

This demographic growth is the outcome of a unique combination of large waves of immigration, a process limited by the Law of Return to Jews and their kin, and high birth rates, especially in the first decades of statehood, both among Jewish immigrant women from Asia and Northern Africa and among Muslim women. Nearly one-third of the total growth of the Jewish population traces to immigration; natural increase accounts for the rest.

There were times, however – until the 1960s and again around the collapse of the Iron Curtain in the early 1990s—when immigration was paramount in the growth of the Jewish population. Given that most Jewish communities in areas of distress have emptied out, immigration has declined recently and has become a small component of the demographic dynamics of the Jewish population in Israel.

Population growth

Although Jewish demography has benefited from both immigration and fertility while that of non-Jews has gained from fertility only, the latter population grew at a slightly faster pace due to many years of very high birth rates, around ten children per woman. Recently, however, these rates have come down; notably, Jews and non-Jews have very similar numbers of children today: three per woman on average.

Accordingly, the ratio of Jews to non-Jews in the Israeli population has fallen slightly over the years, to 79 percent vs. 21 percent. This takes into account all residents of Israel within the Green Line, including eastern Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, and Jews who live in the West Bank (but not Palestinians in this area).

The Jewish population also includes immigrants, mostly from the Soviet Union, who are not Jewish according to the halacha (Jewish religious law) but are entitled to immigrate to Israel under the Law of Return. (They are also defined as “people with no religion.”)

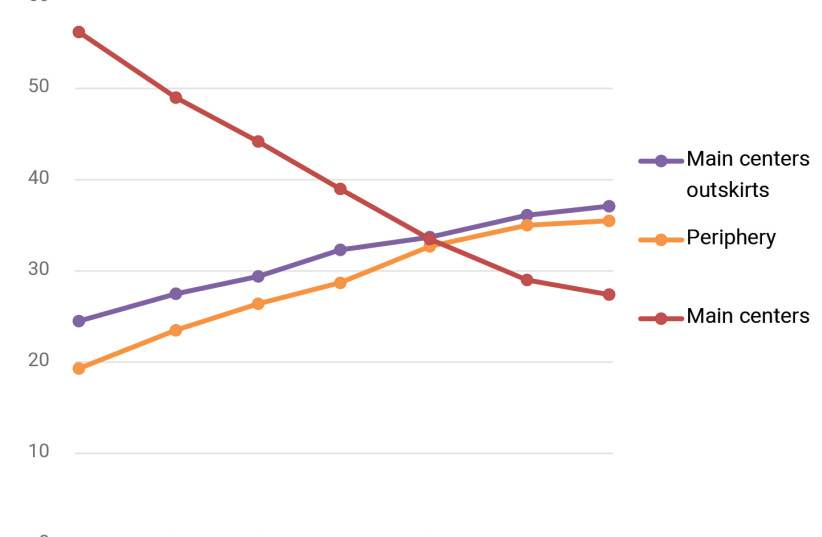

If they are not collapsed into the majority group, the proportion of Jews in the current Israeli population falls to only 74 percent. Amid these demographic processes, the geographical distribution of the population has also changed. Much of this, of course, was driven by the geopolitical changes that followed the Six Day War and the expansion of Jewish settlement into new areas.

Some, however, originate in revisions of residential preferences accompanied by internal migration of the non-immigrant population, uneven dispersion of immigrants, and differential birth rates in towns and cities by level of religiosity, accounting for the changing share of the Ultra-Orthodox (the Haredim), among other outcomes. It is especially noteworthy that the residents of Jewish settlements in the West Bank account for around 6 percent of the total Jewish population in Israel at the present writing.

Likewise, unlike the formative years of the country, in which people of Asian-African origin were overrepresented in peripheral areas and European immigrants were overweighted in the center, the Jewish population today is much more ethnically balanced in the various regions. And while around seven percent of the Jewish population lived in kibbutzim when Israel was established, only 2.5 percent do so today.

Finally, the Jews of Israel constituted a mere six percent of world Jewry in 1948. Today, in contrast, more than four out of every ten Jews in the world live in the Jewish state. Together with the US, these are the two largest Jewish concentrations in the world, largely equal in number.

The writer is head of the Division of Jewish Demography at the Institute of Contemporary Jewry of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where he also holds the Shlomo Argov Chair in Israel-Diaspora Relations.

This is the first in a series of eight op-ed articles that will appear once a month through Independence Day 2023, marking Israel’s 75th anniversary. Each article deals with a different social and cultural aspect of modern Israel. The main source of data in the articles is the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics; citations from other sources will be referenced appropriately. The next article discusses aliyah.