‘We are all flowers,” said American artist Daniel Gibson, in Israel for the first time to present his one-man show at the Nassima-Landau Art Foundation in Tel Aviv, curated by Steeve Nassima.

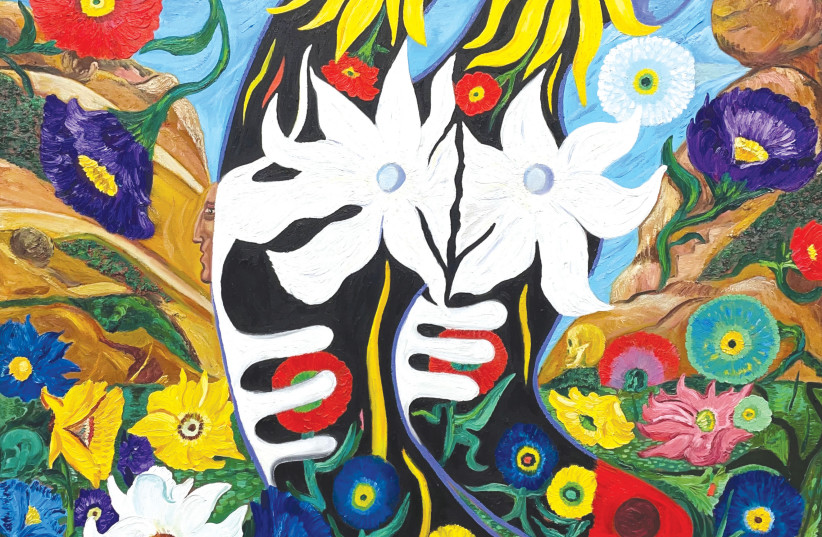

Gibson’s large paintings seem happy at first glance. The beautiful, colorful flowers are created with thick layers of paint, bold brush strokes and a good deal of texture.

Soon enough you uncover what they are hiding.

The Jerusalem Post caught up with Gibson in Tel Aviv.

Both Gibsons’ parents came from Mexico as children. He grew up on the American side of the Mexican border. His paintings tell the story of his life; his family; and the people who try to cross the border from Mexico.

His grandmother on his father’s side had a Taco stand near the border, on the Mexican side. Gibson[’s paternal grandfather] was a white train worker from Oklahoma who frequented her restaurant and fell in love with her.

“He took her and her four children and brought them to the USA,” Gibson says.

Gibson senior had family in Oklahoma. They were pig farmers and they could not understand why he went and married a poor Mexican woman with four children that did not even know English.

“Their life together was cut short when he fell from the train and broke his back. His white family didn’t even let my grandmother visit him there, because she was a Mexican peasant woman,” he says.

The artist’s father adopted the Gibson last name “to honor this good man, who took the role of father and even gave my dad his first Gibson Les Paul guitar, which is rare now,” he smiles.

How Gibson's upbringing inspired his work

GROWING UP in a small industrial town, Gibson felt he didn’t belong. “My whole life it’s always been like: ’You’re not Mexican enough,’ [or] ‘You’re not American enough.’ “White people would say ‘Oh, you’re not like those dirty Mexicans,’ but hey, actually, I am. “Or the Mexicans [would be] going, you’re with them white…”

For Gibson, his whole life has been “this idea of not belonging.”

Mexico is very present in his art, although Gibson says it is unintentional.

“These paintings are coming out of me,” he says.

“I think that I am expected to paint the Chicano, you know, with a fist in the air, yelling, but I don’t. I grew up in a bad neighborhood and I don’t talk about that too. I don’t glorify gang members because I didn’t like them and they didn’t like me. I rather talk about humanity and struggle, and my struggles,” he says.

At 27, Gibson moved to LA to go to art school but didn’t stick it out for long.

“I dropped out of art school because I could not afford it,” he says. “The teachers were like ‘You have the thing – just go do your thing’.”

“I had to teach myself,” he smiles. “To be an artist you have to be completely crazy, you have to be obsessed. I knew I had to be obsessed,” he says.

Gibson recalls: “Many years ago, my dad and I were sitting outside talking, and my dad was commenting on some small success I had – maybe I sold a small painting. He said he thought Gabriel, my little brother, would be the artist in the family because he could draw anything. I said ‘He is an artist but he is not stupid enough or crazy enough to do this year in and year out.’”

The road to success was not always smooth. Gibson became addicted to drugs and alcohol, and at one point was close to dying.

“I am celebrating nine years of sobriety, but those years were very dark. My art was very dark, and no one wanted it. I didn’t want it. I didn’t even finish my works. I loved the idea of being this dark artist – that is smoking and drinking and yeah… but I never really produced anything,” he says.

Gibson defines himself as someone who has gone through addiction and come out the other side.

“Knowing what it is to be ‘knocking on death’s door’ and coming back, I really appreciate getting to paint every day,|he says.

“I was supposed to be dead. A lot of what is in the paintings is me coming back from the dead. I have lost many friends to addiction and mental problems. Some of the paintings talk about that too. The people I lost – I am speaking for them: my friends that left this world.”

“I think many artists are scared of life and more so of death. Why else would we make all these things to put into the world?

“I think that it is so when we die we can still leave something behind. A musician, he writes music and years after he dies we listen and enjoy [it], we make love to this music, we cry, we celebrate birthdays. They still live on. I feel when I leave this body I know that these things will still be there. I think this is beautiful.”

Gibson, who is “severely dyslexic,” finds it hard to read and write.

“I could never write anything down. I had a band and I used to play music, but I never wrote one lyric. I had to memorize [them],” he says.

“But I still want to tell a story. I want to tell the story of people crossing the border – how they felt and how they looked, and how I felt seeing them when I was a kid.

“Some people just want to live their life quietly, I never wanted that. I needed to tell a story to the world.”

Gibson chooses to paint the migrants as flowers.

“I didn’t want to show their faces because as a child I remember them always hiding. Not showing their faces. They hide their papers and passports so they cannot be taken back to Guatemala, or another place. From Mexico, they can try again.”

For him, the flowers are “almost like people.”

“I always ask them what they want to do. I don’t open up a book of flowers. I put a lot of paint and talk to it,” Gibson says as we move from one painting to the next.

“Look, this flower is running, this one is stepping upstairs. And the butterflies. They are in profile and see – there is the profile – and it is human. Maybe it looks like me. And you see the eyes, and the rib cage,” he says.

Gibson does not want to “exploit” the faces of the migrants “in a painting that will be purchased by a rich person and I will make money.”

By showing them as flowers he is saying that “we all need the same things, like flowers.”

“We need air and sun and water, to live. And you put a flower next to weeds and they will take over. That’s like bad people.

“The butterfly is coming down to scoop the flowers. These are immigrants, and the butterfly brings them to safety.”

As a child, Gibson would see migrants passing in the night.

“I used to worry [about] how are they getting to safety – where are they going. Later I came up with this idea of, maybe a butterfly came and picked them. It is like a dream, a naïve dream.”

Gibson paints the Arizona desert.

“There are big boulders in the area I am talking about, big rocks,” he points at them in his paintings.

“And there’s the border wall, but I make it small. I don’t give it the power anymore. The flowers are larger than the stupid border. These flowers, they are people. We are all flowers. If I put you in a dark room – how will you survive? If I put you in the sun and give you nourishment – you will bloom – you will open up. We are the same as flowers.”

Gibson doesn’t want to talk about politics, he just wants to help.

“If someone twisted their ankle and they are in the middle of the desert, I want them to have water and medical supplies. I don’t care about the politics. I just want that if you are hungry you will get food. If you are sick you will be treated.” he says.

“And it is not only Mexicans. There are many Asians and others who try to cross the border. People will continue to come because they do not have a choice. They want to live. They cannot stay in their homeland. They would love to stay in their country, but they cannot. They need safety, they need food and they need to know that no one will kill them. They have zero choice,” he says.

“Mexicans want to stay in Mexico but the small towns are taken over by the cartel. The small town where my mother’s family – the Garcias – came from, the whole town was decimated by the cartel. No police go there ever, and everyone leaves. It is a ghost town.”

Gibson wants to use his painting to send a message.

“This is a way for me to try and figure out how it is to migrate. It is such a hard thing, but a part of me wants to make it easier to digest it. I want people to enjoy the paintings and be interested."

Gibson belongs to an organization called Border Kindness – www.borderkindness.org (@borderkindness).

He refers to the volunteers as “angels,” and explains that they “set up water drops and leave water and medical supplies, blankets and equipment for the kids..., ” and even provide acupuncture and dental care, he says.

Gibson contributes to the organization’s fundraising by donating paintings.

“And I am trying to raise awareness,” he says. His goal: making the kids feel safe [even] for a while.

Daniel Gibson’s ‘Pathfinders,’ is showing at the Nassima-Landau Art Foundation, 55 Ahad Ha’am street, Tel Aviv until June 8.