‘The painter constructs, the photographer discloses.” These decisive words were penned in the authoritative tone of none other than American writer, filmmaker and philosopher Susan Sontag in her seminal book of 1977, simply titled On Photography. The book, which binds together a series of essays that the illuminating thinker had published in the 1970s in The New York Review of Books, was and is still considered a watershed volume in the field of theoretical writing about culture, art and the effect photography has had on our contemporary society.

Myself being an advocate of the former medium over the latter (due to a simple and subjective matter of familiarity and personal preference), I couldn’t help but ponder Sontag’s axiom as I walked around the vast complex of Tel Aviv’s Daniel Rowing Center earlier this week, ahead of the opening of the country’s international photography festival. The athletic compound, overlooking the peaceful, green backdrop of the city’s Hayarkon Park, will house for the following weeks the works of hundreds of photographers – both local and international. The festival itself is considered the very climax of the year for PHOTO IS:RAEL, a nonprofit working towards “a better society through the language of photography,” as its website boasts.

The cultural event is noteworthy and worth a visit, even for those of us who beg to differ Sontag’s dichotomous distinction between artists who create their response to reality versus those who depict it through the penetrating eye of the camera lens. For one, the diverse festival, which includes a whopping 105 mini-exhibitions, is open to the wide public free of charge. Another attraction lies in the fact that after a couple years of social distancing and limited air travel, Israeli photography connoisseurs are provided rare viewing access to works of major international artists – an exciting occasion in a cultural scene that is quite neglectful of the medium and where only a handful of galleries are fully dedicated to researching and displaying photography and video art.

Impalpable presences

Among the dozens of projects on view in the festival, some of the most compelling works are to be found in the central exhibition, Meeting Point, which also serves as the theme of the festival this year. The exhibition highlights the works of artists who applied to an open call that bore the name of the exhibition and who were selected out of hundreds of entries from overseas and from Israel.

Chief curator of the festival, Yaara Raz Haklai, remarked to journalists touring the festival that she was moved but perhaps unsurprised to discover that in the post-COVID-19 reality, most of the projects submitted, and those selected by a special committee, had revolved around the quest for a home and familial connections or raised questions about the boundaries and healing capacities of the body.

This seems like an apt description for the work of Italian photographer Silvia Alessi, whose series Maze of Metamorphosis focuses on individuals who suffered acute physical trauma and have overcome it or continued creating in their respective fields despite the hardship. One of the most poignant images she has created is a portrait of Japanese dancer Koichi Omae, who lost his leg during an accident. Staring almost tauntingly at Alessi’s camera, Omae is seen balancing all of his weight on one hand, his torso straining as his other limbs are extending gracefully upwards.

The body, or its painful insulation in the absence of other bodies, is almost only hinted at in a riveting series by Italian photographer Davide Bertuccio. The Silent Clapping of Their Hands is a poetic project offering a peek into the inner life of Claudio Madia, a 60-year-old ex-TV presenter who lives in a colorful and isolated home in Milan. Bertuccio told online photography magazine Lens Culture that Madia previously organized circus shows, but when the lockdowns began in Italy he was forced to shelter in his home and “was left without an audience, except for those he had drawn himself on his walls.”

Bertuccio captured Madia in playful moments when he carried out performances with neighbors and friends, but also managed to turn the entertainer’s solitude into a touching photographic essay as he documented Madia stretching in fatigue amidst the chaos of his private rooms in the last light of day, or highlighted the shadow Madia cast on an outstretched bed sheet as he exercised his acrobatic maneuvers for the eyes of his imaginary audience.

Growing pains

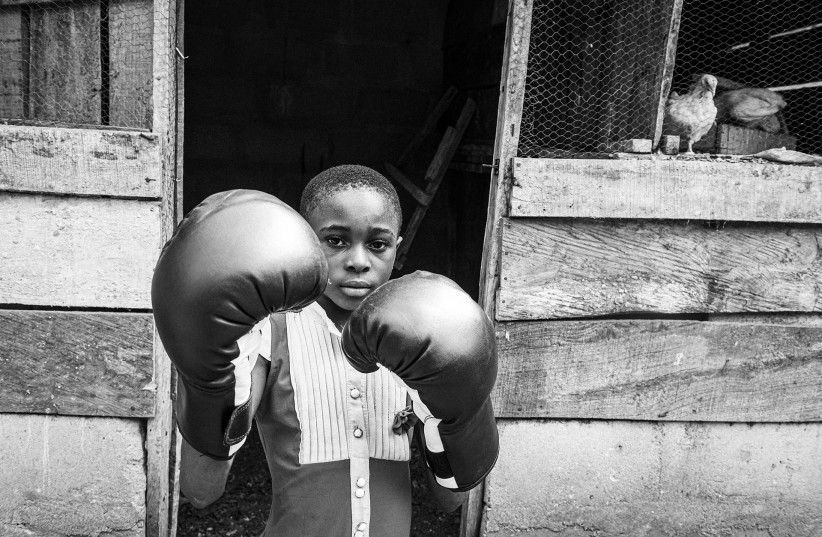

The pain suffered by the female body, its changes and the marks society leaves on it are the focal points of Cletus Nelson Nawadike’s project. Originally from Nigeria, Nwadike immigrated to Sweden, where he resides today and creates in the mediums of photography and poetry-writing. The name of the series he is presenting at PHOTO IS:RAEL, which he created in 2020, is self-evident: Girls Struggling in Nigeria.

Nwadike returns to his homeland for photography sessions, where he depicts the complex and everyday reality of its citizens, who still suffer from immense discriminations and various hardships despite the African country’s official post-colonial status. “I seek to honor all Nigerian girls who continue to insist on their education despite the many challenges,” Nwadike wrote of the black-and-white series featuring portraits of girls and women he photographed in rural and urban environments. A young girl wearing an earnest expression and clad in boxing gloves, a woman whose eyes are covered by a money bill and a woman standing almost defenseless with eyes softly shut in front of his camera all belong to staged but nonetheless irradiating scenes Nwadike constructs (here Sontag’s claim about photography’s role as a truth-bearing medium devoid of artifice seems to crumble somewhat).

A different coming-of-age project was manifested by Canadian photographer Tim Smith, who spent 12 years on the prairies documenting the lives of Hutterites – insular Anabaptists who live in colonies in Canada and the US, and who mostly engage in agricultural activities to make a living. In sharp contrast to Nwadike, Smith’s images are colorful and full of movement, appearing at first glance to exalt the pastoral existence of the community members he followed for years. A closer look at photographs such as one whose subject is a toddler holding tightly onto a baby doll dressed in the same tones as her evokes unease, bringing to mind questions about the amount of independence women in the communities actually retain behind closed doors and away from the gaze of Smith’s camera.

A last highlight from the exhibition but certainly not the least is a project by east-Jerusalemite photographer Saja Quttaineh, a recent graduate of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design whose eerie pictures of abandoned cityscapes and neighborhoods implore quietly that we pay attention to the charm and aesthetic of urban decay but also acknowledge why certain Israeli communities are more overlooked than others.

While the argument over Sontag’s claim on the nature of photography as a medium meant to unmask the truth and not further layer it is unlikely to be resolved in this column, the visit at the festival underscores how right she was in going on to write that “a photograph is both a pseudo-presence and a token of an absence… photographs are incitements to reverie.”

While clearly different in technique, style and subject matter, the strongest talents on view at the festival – be they from rural Nigeria or the unkempt neighborhoods of Jerusalem – all tell stories of yearning: For viewers, for independence, for education, for the end of a pandemic, for the presence of other bodies and the lives built around but not in spite their absences.

PHOTO IS:RAEL opened on November 17 and will run until November 27 at Daniel Rowing Center, 2 Rokach Boulevard, Tel Aviv. More details can be found at: https://www.photoisrael.org/