Having viewed numerous exhibition lineups at the Jerusalem Artists House over the years I can declare, wholeheartedly, that under the steady hand of director Ruth Zadka the venerable institution has produced its fair share of intriguing, thought-provoking rollouts. However, I have never felt such a seamless common thematic sensibility as that which fuses the current quartet of shows. “It wasn’t planned that way,” says Zadka. “You know, sometimes you start something and you don’t know how it will work out.” Sounds like a pretty concise definition of the artistic process in general.

The works, which will be on display through to October 2, are exciting, moving, shocking, evocative and run across practically the full gamut of emotions and cerebral spectrum. The Mis(s)placed photographic showing by Noa Livnat Agmon ticks those boxes and then some. For the past few years Livnat Agmon has been dividing her time between Israel, where she was born and bred, and Britain where her husband is currently studying. The parenthetical slot in her exhibition title references feelings of detachment and searching for a sense of belonging as she oscillates between very different cultural and social milieus.

“The brackets in the title talk about the emotion of missing something, somewhere,” explains Livnat Agmon. “It is about not being entirely sure where you are, and where you belong. There are painful feelings of terrible foreignness.”

It is very much a “neither here nor there” scenario that feeds into the show. It is about the yawning cultural and physical chasms between the photographer’s homeland and the alien society in which she spends much of her time, and about looking for common ground.

In Mis(s)placed Livnat Agmon tries to almost force the two disparate worlds together. That fueled her choice of monochromic-visual presentation which nullifies the discrepancies between Israel and the UK in terms of the intensity of natural light, and the vibrancy of the meteorological and flora color palette.

That comes across clearly in her Patchwork exhibit, a four by four rectangular composition with images of spindly, sparsely leafed, tree branches against celestial backdrops. It is almost impossible to discern which were taken here and which in England. The emotional tug-of-war is frozen there, and presented in stark yet confusing terms.

Aching pining notwithstanding, Livnat Agmon says she gradually began to take a more positive approach to her peripatetic circumstances. “I tried to marry the best from here and the best from there, and create a new domain.” It is a recurring theme in her evolving oeuvre. “I do that quite a lot. I take an image from the past and an image from the present, two entities which wouldn’t normally meet, and I try to generate some possibility of that taking place.”

Livnat Agmon wants to confuse herself and, thus, us too. “I like to mess around with my memory so, when I look back on them a few years down the line, I wonder where they come from, and what belongs where.”

The perception of displacement, and indecisiveness, also lies at the core of Itai Ron-Gilboa’s Heavy Air installation-exhibition. The centerpiece of his principal display area features three iron frames, all tall enough and wide enough for the viewer to slip into but, once there, you wonder whether, in fact, you are inside or still outside.

The skeletal objects are made of thin black iron rods which, while they are patently designed to accommodate us, do not imbue any feeling of refuge. “There are boundaries here, and the absence of boundaries,” Zadka observes.

Similar to the anthroposophic educational way of thinking, whereby small children are encouraged to dot the “i”s and cross the “t”s, by intentionally leaving out finer natural details, Ron-Gilboa notes that “absence is more powerful than presence.” This prompts questions of meaning and purpose. “His works offer an interesting view of the relationship between empty and full, creating simultaneous awareness of matter and its absence,” explains curator Galit Semel.

The detachment-attachment balancing act also informs the spread of appealing cardboard cutouts, suspended in iron rod shapes that echo the aforesaid triptych centerpiece. One which particularly caught my eye shows a tree with all the expected arborous accoutrements – foliage, branches, trunk and roots – only the tree does not feel rooted at all.

The limbo mindset is also evident in the clutch of paintings on the walls either side of the large metal frames. “I used the plastic backing that you peel off wallpaper rolls,” says Ron-Gilboa. The choice of eminently inappropriate, and unaccommodating, base material was based on both ecological and logistical considerations. “It is a cheap substance and it doesn’t allow you to have much control over how the paintings come out,” he adds with a smile. Indeed, the predominantly pinkish-leaning works seem to leak out in every which direction. The laissez-faire approach produced fetching results, and it is fun to try to reconnoiter the path of the meandering directionless paint made across the plastic surface. “It is also about transparency, in all senses of the word,” the artist adds, harking back to the focal point of his exhibition.

There is a pervading sense of yin-yang counterbalance between Heavy Air and the neighboring Nephilim showing by Noam Omer. It is a suitably named spread, with the reference to the biblical outsized characters inferring great physical strength but also vulnerability, much like Ron-Gilboa’s offering.

“There is a common denominator between the two exhibitions,” Zadka posits. Itai sets boundaries and he also breaches those boundaries. Noam, meanwhile, also has borders and exceeds them.

Then again, there are some marked discrepancies between the adjoining shows too. While Ron-Gilboa infuses his works with delicacy and fragility, Omer exudes a relentless feral bent which threatens to spill out of control. “At first glance, Noam Omer’s works elicit an experience of excess: a surplus of images, an inundation, flood, eruption, visual blast, a congestion of lines referring to lines, stains referring to stains,” says Semel who, incidentally, also curated Nephilim. “Omer is a total artist,” she adds.

She could say that again. My mouth unconsciously opened up into a “wow!” shape as I entered the space with Omer’s large canvases. You are almost blown off your feet by the torrent of oil, watercolors, ink and charcoal that meet your eyes, and heart. This is clearly the product of an intense mind and an unforgiving approach to venting artistic creativity, come what may.

The dynamism of the Omer spread is underpinned by a powerful oxymoronic marriage of “the tragic and the mundane, the absurd and the logical,” Semel notes.

You are drawn into the vortex of the artist’s living and work space, and also repelled as the beauty and the monstrousness of his mode of expression hits you, and hits hard. “Father Crucified” is a plangent sounding board that resonates across the pictorial layout. One wonders how, indeed, Omer got along with his dad and whether the Jesus-like figure, which pointedly jars against any stock Christian iconography, is meant as a statement of evil intent or as an expression of empathy toward his parent. Away from familial considerations, John Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian-American who served as a Nazi camp guard at Sobibor extermination camp, who was convicted for being an accessory in the murder of tens of thousands of camp inmates, gets a suitably demonic visual reading.

Distortion and amplification are very much the name of Omer’s creative game. “The works on view address a tragic-grotesque experience of existence,” says Semel. Indeed, there is little in the way of a breathing space as you work your way across the paintings. But it is hard to evade their mesmerizing pull.

Things are a little less intense in the second Nephilim display space, over at the far end of the Ron-Gilboa exhibition. While the largely monochromic elements of the canvasses recur here, the ceramic bowls and plates are generally more colorful and, hence, convey a softer ethos. That is not to say that the energy level drops here, but the pottery paint polychromy is easier on the eye.

And, if you get to pondering Omer’s artistic points of reference, one look at a bowl with a mostly red-pink bearded face, augmented by some brusque brushstrokes, puts one immediately in mind of Van Gogh’s darkly tempestuous Wheatfield with Crows. Whether Omer consciously fed off the 1890 painting, with its furtive swirling lines that heave, ebb and flow, is anyone’s guess. But the troubled sentiment is definitely there in the creative mix.

Monochrome reappears in the Tama spread by Ruth Norman on the mezzanine floor of the century-old building. The same goes for the idea of home, and belongingness. Norman was born in Israel in the mid-1950s, the daughter of German Holocaust survivors. And while, in terms of geography, she grew up in the Middle East her domestic cultural backdrop leaned heavily in the direction of Europe.

But, sometimes you have to step out of your natural habitat, and your comfort zone, to discover your inner feelings and thoughts lurking beneath your external cognizance. For Tama, Norman immersed herself in Persian folklore as she deconstructs and refashions figures and motifs she espied in a Persian rug she came across while visiting a friend’s home.

Like Omer, Norman is a stickler for detail and digging into the minutiae even when, for her, the visual and cultural baseline is in the realms of the extraneous.

Tama is the issue of an entire year spent examining and deconstructing the said embroidered fabric. All told, Norman painted 48 fragments from the rug, focusing on human figures, animals and scenes taken from Persian fables.

The method she employed for presenting those vignettes is pretty remarkable. Her technique, which she has honed over some years, involves the use of correction fluid – aka Tipp-Ex – in various degrees of dilution.

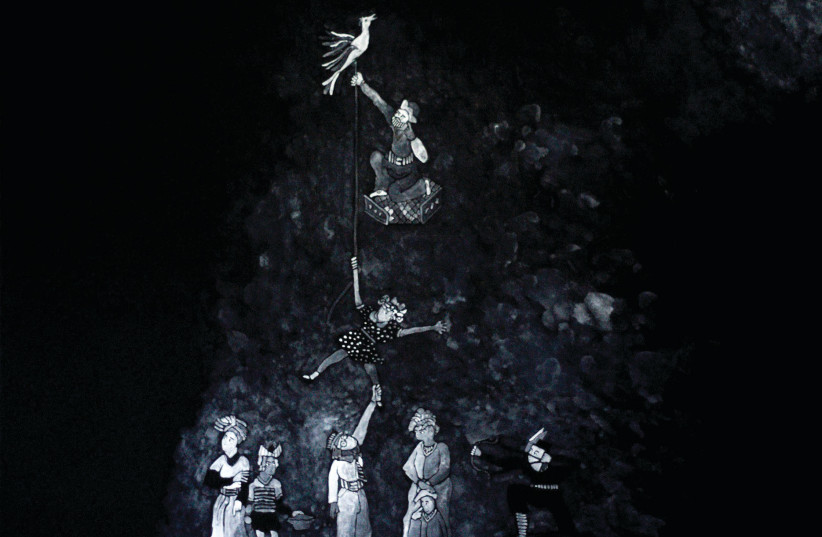

The couple of dozen or so of works that make up Tama were created by applying the white liquid to black paper. Such is Norman’s expertise with the unlikely tool of trade that she manages to produce convincing story scenes with a broad range of figures, and also creates dramatic and amorphous textures and landscapes.

The eponymous character is a girl who grows into womanhood, and tells the story of developing consciousness. “Precisely in this complex and foreign world of images, the artist found an accommodating space in which to tell her story,” notes curator Meydad Eliyahu. The end product is, indeed, compelling.

For more information: (02) 625-3653 and www.art.org.il