Mother Nature operates on the basis of ongoing fine tuning. There are checks and balances built into the system which, to put it bluntly, have enabled this timeworn planet of ours to continue to exist, despite our continuing best efforts to batter it into oblivion.

The equilibrium element also lies at the core of a fascinating and evocative exhibition, with the curious title of Fine Structure Constant, currently hanging on the walls of the Agrippas 12 collective gallery.

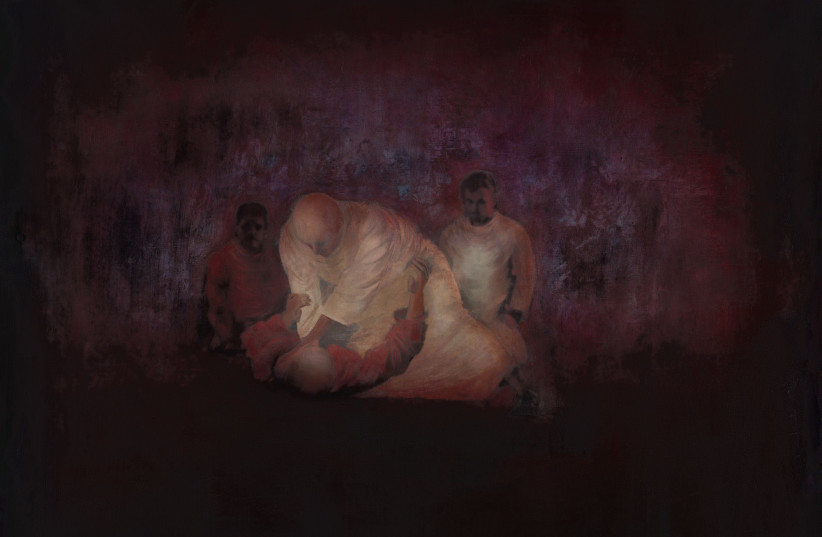

The 18 works, created by Sarah Nina Meridor, feed off the biblical saga of Jacob wrestling with an angel. The tussle, we are told, ebbed and flowed through the night, and that pivoting act is portrayed in the oil paintings, along with various other references to a slew of fluctuating states.

At first glance, the display looks a little like a comic book spread. The works are packed pretty compactly, creating a sort of storyboard frame sequence. That is the primary drawback of the limited cooperative display space. Then again, after all, there is a storyline to the biblical source so, perhaps, the absence of a more generous wall surface may actually contribute to the continuum perception.

Meridor presents the protagonists in all sorts of poses, dynamics and, even, basic quantitative presence. There are figurative scenes, and pictures that tend more to the abstract, dreamy, side. Some have detailed facial features, others have none at all. In some paintings the protagonists are naked, and there are fully clothed figures, and some covered to the point that their corporeal attributes are indistinguishable.

All the above, and more, are grist to Meridor’s storytelling endeavor, and even the absence of information seems to infer some subtext or other. There is also deft usage of light and shadow interplay, as well as chromic spectrum dovetailing which, largely, uses the stark contrast between one figure in red – representing the visceral animus, life itself – and one in white, inferring purity.

That is part of the general plan as the multi-pronged line of artistic attack serves as a vehicle for examining accepted wisdom and conventions – which tend to spawn preconceptions – regarding good and evil. “Light is meaningless without the dark,” says Meridor, adding some thoughts about our socially acceptable value system in general. “When good reaches a certain point it generates stagnation. Stagnation is a way of life. That is a sort of death. It is worse than darkness which, at least, offers the promise of something else.”

There is plenty going on in Fine Structure Constant. There are the base dynamics of the wrestling meet. And the continually shifting interface, as one or the other gains the temporary upper hand, provides the viewer with numerous visual points of reference and angles on how to ruminate about the proffered food for thought.

The oscillatory flow is core to the exhibition and, naturally, to Meridor’s thinking about art and about life in general. “There is this delicate balancing act, on the thin blade edge of a knife. Without that it is all simply uninteresting.”

But it is not just about two bodies, physical, spiritual or, indeed, metaphysical in nature. Meridor also considers the ethereal, the seemingly nebulous components that are inherent to the relationship between any two entities, including the ostensibly empty space between them.

The exhibition title is designed to convey that state of reciprocity. The show background material, written by Michael Simkin and Peggy Cidor, explains that the moniker is “a term taken from the world of physics which describes the force of electromagnetic interaction between elementary charged particles. It is a dimensionless quantity, which expresses the strength of the coupling of particles with the electromagnetic field. This phenomenon, fundamental to the physical world, is symbolic of our condition and inexorable contract with existence.” That sums up the pictorial spread, and the artist’s intent, pretty neatly.

There is also the odd cultural crossover to the venture. “The fine structure constant is denoted by alpha, the first letter of the Greek alphabet,” the blurb continues. “In the Greek numeral system, alpha represents the number one and symbolizes the beginning and the primal. Etymologically, alpha came from aleph, the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Ironically, the word is also used to indicate the dominant male.”

The latter is key to the exhibition subject matter, as both Jacob and his angelic counterpart do their damnedest to overcome their foe. But, as Meridor sagely notes, when it comes to violence there are no real victors. “Each of the combatants, in any fight, never comes out of it the same. They always come out with the fallout of the experience.”

That also applies to the joust mentioned in the Torah. “At the end of the fight, in the morning, the angel asked to be released, but Jacob refused to do that without getting something from the angel. The angel then blessed Jacob and gave him the name Israel.”

But what do we really know about the nitty-gritty of the altercation? “I have always been intrigued by what happened that night,” Meridor continues. “We were all brought up to think of angels as protecting us and as good things, you know, like some cupid with a bow and arrow making people fall in love,” she laughs.

This celestial being was clearly made of different, sterner stuff, and Meridor was determined to get to the bottom of it all. “I read a lot – midrashic texts and other sources,” she notes. The results of her excavational efforts set the wheels in motion for further exploration, and fueled her easel work. “Some say that this is a story about a person vying with their own shadow, with their alter ego, with their ‘other side.’ Some say it is about soul searching between Jacob and Esau.”

That is alluded to in the first work the visitor encounters as they enter the corridor that leads into the main display hall. It is also the only non-oil picture. The charcoal drawing simply shows a woman’s midriff, the inference being the subliminal, subcutaneous coexistence of the aforementioned biblical twins. “Something very significant took place there,” she says, referencing the birthright saga in which Jacob successfully pulled the wool over his father Isaac’s unseeing eyes.

Meridor believes Jacob came out of his bout with the angel with some highly meaningful detritus. “After he won the fight, he didn’t let the angel go without demanding a blessing from him. So he came out of it with a new name.” He also ended up with a limp after his adversary left his mark on Jacob’s thigh tendon, but Meridor feels he gained some important ground too. “You don’t always come out of a battle in one piece, but Jacob used the opportunity to move up a level. He was determined to turn the predicament into an advantage.”

Moving up a level? In what sense? Perhaps in terms of his own sanctity? Meridor isn’t too sure about that. “I don’t know if we are talking about a degree of holiness here. I think it was about Jacob’s ability to influence others.” To my 21st century ears that seemed to infer some political intent. “No, that isn’t accurate,” Meridor counters. “I think it is about how he influenced himself, and others in a good sense. We always have some impact on others, through our interaction with our environment. There is always reciprocal impact between people in the common domain.”

All of that, and more, comes across in the paintings, which run the gamut from lush hues to milder, almost bland, shades and from clearly defined figures to ambiguous amalgams and less determinate portrayals.

Much of what Meridor has put out there, in the gallery, is about the see-saw nature of our existence, and the world around us. “It is like with music. When you make a sound, as it travels through emptiness nothing happens. It is only when it hits something, when it encounters resistance, that you can hear the sound.” That, she suggests, lies at the heart of all our sensorial experience. “The echo is what I mean when I use the word influence.”

She got an enlightening taste of that, on a definitely personal level, a few years back when she was traveling in India. “I went to a small Buddhist temple. The temples always have a statue of Buddha – the Japanese have them in bronze, and in India the statue is golden. But I couldn’t see a statue anywhere.” She turned to a woman there and asked about the statue but the woman just pointed in a particular direction. There was no statue to be seen. It took a while before Meridor noted the mirror and her own reflection, as it were, her own echo. The divine, she concluded, is inside each and every one of us.

The paintings not only center exclusively on the tussling twosome. There are works where the two merge into one, and there is one canvas in which the clash is observed by a couple of onlookers. The fact that Jacob and the angel are seen rubber-stamps their existence. That, naturally, evokes the age-old philosophical dome scratcher of whether a tree can be said to have made a sound if it falls down in a forest and there is no one around to hear it. But, in including an audience along with the jousters, Meridor skirts around that particular cerebral minefield.

The thematic biblical skirmish also provides some insight into some of the interpersonal societal undercurrents that not only inform life here, but everywhere. “Art is a universal language which can give us access to Jewish tradition and mythology, and develop our identity but not from a religious place.” The artist believes we can all get something from the tale of the Jacob-angel hookup. “They are sort of archetypes. There is a Jungian idea of a kind of umbrella under which we grow – our country and nationality – and we can develop our identity, and approach the stories which can help us, for example, at times like this.”

Meridor, like the rest of us, is fully aware of the quandaries we have faced over the past 18 months or so, and how we have decided to deal with ongoing challenges as well. “We can look at our relationship with the other – people who are vaccinated and those who choose not to be vaccinated, right-wingers and left-wingers, Jews and Arabs, religious and secular people – and see that, at the end of the day, we end all our disputes by fusing together,” she states, with a nod to a particularly striking canvas in which it is impossible to tell the protagonists apart.

At the end of the day, of course, as with any artistic offering it is about individual perception and interpretation. Once an artist puts the fruit of her or his creative labors out there they are at the mercy of the viewer, who brings their own intellect, emotion and other baggage to the fore. Still, Meridor thinks there are some objective elements involved that we could all do with consciously taking on board. “If we stop using names to define situations and things we have a chance to change our paradigm, and find ourselves in a different reality. To do that we need to stop being subjective.” That also implies an attempt to take a step back from our judgmental take on life, and those around us. “You give someone a label, and then you stop seeing them as a person. We need to stop doing that.”

Far easier said than done but, for now at least, there is plenty to feast our eyes – and thoughts – on over at Agrippas 12.