Mervyn Trappler is a Jew from a country that changed its name four times within 24 years due to war and political upheaval.

Trappler was born in 1956 in the self-governing British Crown colony of Southern Rhodesia.

Jews played an integral role from the country’s beginnings. Southern Rhodesia was founded in 1890 by the British South Africa Company led by the British imperialist Cecil Rhodes and his German-Jewish partner, Alfred Beit. Jews formed Rhodesia’s first synagogue in a tent in 1894 in Mervyn Trappler’s birthplace, the southern city of Bulawayo. Three-hundred Jews lived in Rhodesia by 1900.

The Rhodesian Jews came from everywhere. The initial wave came from Russia and Lithuania. In the 1930s, Sephardi Jews from the Greek island of Rhodes arrived and settled in the capital city of Salisbury (now Harare). German Jews also came to the country fleeing the Nazi persecution of the 1930s, followed by their coreligionists from Congo fleeing the civil war that broke out following independence in 1960.

The Rhodesian Jewish community reached a peak of 7,060 in 1961.

Diversity

Mervyn Trappler’s origins echo this history of Jewish diversity. Trappler’s mother, Ruth, was born in Bulawayo. Her family originally came from the Eastern European region of Galicia. His father, Jack, was born in Capetown, South Africa, from Dutch Jewish origins.

Trappler lived a charmed life and childhood in Bulawayo. “We lived the most exceptionally privileged, wonderful lifestyle,” he says. “Our life was exceptionally easy. Most households had servants. Everything was done for us. Work hours were basically eight to five.”

His school schedule was from 7:30 a.m. to 1 p.m. followed by compulsory sports in the afternoon. Though his mother had a basic knowledge of Sindabeli, Bulawayo’s local African language, “unfortunately, we were not taught [the African languages] in the schools. It should have been required.”

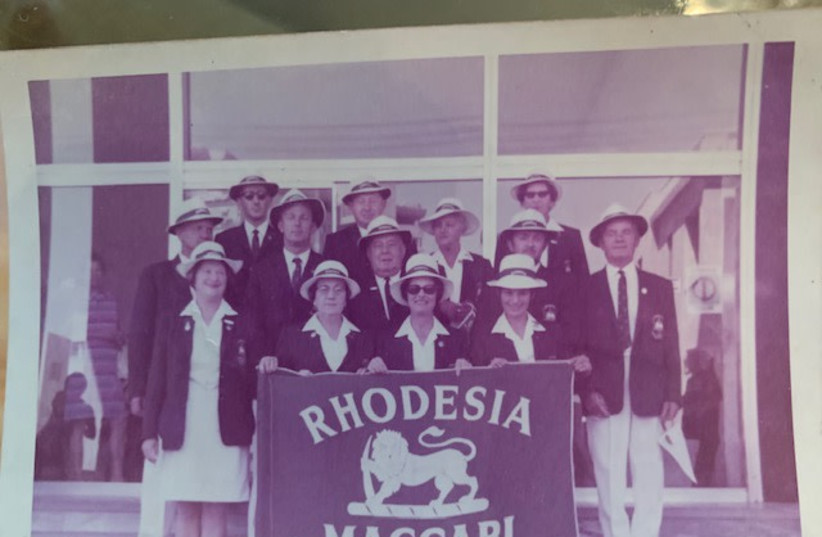

Trappler described the Rhodesian Jewish community as being well-integrated into the larger society.

“Jews participated in sports just like everyone else. Jews participated in every way of life. We were very assimilated... Jews were farmers, Jews were ranchers, Jews were manufacturers... There was nothing, as far as I remember, where we were prohibited from doing anything.”

Jews were well-accepted in Rhodesian society. “I don’t recall any antisemitism. I didn’t encounter any.”

Trappler and his family joined Bulawayo’s Hebrew Congregation Synagogue, the Orthodox shul, one of two in his city. “Probably 90% of the congregation was secular. There was a small section of the congregation that was shomer shabbat and kept kosher.”

Segregation and discrimination

In a society governed and dominated by whites over a black majority, segregation was social, not legal. “We did not have apartheid as such. Whites could marry blacks, blacks and whites could live together. They did live separately. There were different townships. They were prohibited from most things generally for economic reasons.”

Black Africans suffered disenfranchisement through economic means. “The vote was a qualified franchise, in that one had to pay a certain amount of tax in order to qualify to vote, so they [were] disenfranchised, most of the black population. They were subjugated. They were discriminated against.”

As a young man, Trappler disagreed with Rhodesia’s existing order. “There’s no doubt that things had to change. There had to be majority rule.”

“There’s no doubt that things had to change. There had to be majority rule.”

Mervyn Trappler

After World War II, Britain began the dismantling of its empire. In Africa, the British took the position that independence meant black majority rule.

In 1965, with the support of the majority of Rhodesia’s white population, the country made a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) under the leadership of prime minister Ian Smith and his political party, the Rhodesian Front. Britain responded by cutting economic links and attempting a naval blockade of oil to Rhodesia, and the UN-imposed sanctions in 1966.

The refusal of the white minority government to share power with the black majority led to a civil war called the Rhodesian Bush War. Begun in July 1964, it was fought by two insurgency forces, the Zimbabwe African National Union, led by Robert Mugabe, and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union, led by Joshua Nkomo and the white-dominated government, which lasted until December 1979. The war took approximately 20,000 lives.

The Rhodesian Jews broke with the consensus of the white population. “The Jewish population generally was liberal... Jews for the most part were supportive of majority rule.”

“The Jewish population generally was liberal... Jews for the most part were supportive of majority rule.”

Mervyn Trappler

Jews began to leave Rhodesia as Smith’s declaration of independence drew closer.

During his final year of high school, Trappler received his draft notice in the form of an official letter from the Rhodesian Army, in which military service was required upon the completion of high school.

He reported for his physical examination in February 1975 and entered the 9th Battalion, Rhodesian Rifles, the next month.

Trappler faced a difficult situation because he did not support the Rhodesian government at the time of his induction, and believed in majority rule. “The doctor who was doing my physical asked if I wanted to go into the army, and I didn’t know how to answer so I told him that if I had to, I will. He put me into medically unfit. My basic training was reduced and I couldn’t go into a combat unit.”

The Rhodesian Army posted Trappler to a barracks near his family home during his year of active duty. “I had a pretty good year in terms of not doing very much.”

His father also served in the Police Reserve, and was posted on the border between Rhodesia and Zambia.

After his year of active duty, Trappler planned to go to university in South Africa when he was called up for duty as a reservist. A university interview excused him from that particular call-up. He decided to stay in South Africa for school, but the South African government refused to extend his visa and told him to return to Rhodesia. If he returned, he would have been called up again for military service.

To avoid a return to the army, Trappler went to the Israeli consulate in Johannesburg and obtained a laissez passer, travel documents allowing him to go to Israel.

As to his departure from Rhodesia, Trappler said, “I never fled. I left.”

He reached Israel and found himself stateless because only South Africa and Portugal recognized the Rhodesian passport. Trappler visited the British Embassy in Israel and obtained a passport based on his grandfather’s British descent.

As for the overall outcome of the conflict, Trappler described the war and its ironies. “The Rhodesian forces won the battle but lost the war. They were outstanding in what they did in terms of fighting and counterinsurgency. The interesting thing about the Rhodesian Army is that it was 75% black... In Rhodesia, every six weeks you’d be called up for a few weeks and that became untenable. That’s why people started to leave. The economy couldn’t handle all of their people, the workforce, being in the army. That’s how Rhodesia lost. Economically.”

Trappler stayed in Israel for two years, worked on Kibbutz Ramat HaKodesh and met his future wife, Donna Roth in 1976 and they got married in 1979. After multi-year stints in Israel, he and his wife settled permanently in the US in 1997.

Trappler’s parents left for Israel in 1978 to join him and his siblings. The family eventually settled in Ra’anana.

His uncle Nathan Middeldorf remained in Bulawayo and passed away in 2020. Trappler took Zimbabwean citizenship in 1981 and returned every two to three years to visit his uncle and friends.

The Rhodesian Jews scattered to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Israel and the US.

“It’s a very tight community. Everyone keeps in contact. It’s really terrific. But also very sad at the same time because it’s over. We’re all dispersed. When you go home, many of our institutions are no longer there.”

“It’s a very tight community. Everyone keeps in contact. It’s really terrific. But also very sad at the same time because it’s over. We’re all dispersed. When you go home, many of our institutions are no longer there.”

Mervyn Trappler

Trappler added with pride that “Rhodesian Jews generally punched above their weight,” and mentioned the world’s most prominent Jew from Rhodesia, Stanley Fischer, the eighth governor of the Central Bank of Israel who also served as the US Federal Reserve’s vice chairman from 2014 to 2017.

In an effort to reach a political settlement, Rhodesia was renamed Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979. Upon full independence in 1980, the country settled on its final and current name, Zimbabwe.

Trappler entered the sports business and in a nod to the dominant ethnic group from his region of Rhodesia, Matabeleland, he founded Matabele Sports & Leisure Marketing.

In another venture, he set up a partnership called Staydium Travel, which will soon launch a website on which sports aficionados can purchase tickets for any sporting event outside of the US. Serving as an online travel agency, fans will be able to make their own arrangements.

Despite his criticisms of Rhodesian society, Trappler proudly proclaimed: “It was such a privilege to have lived and grown up in Rhodesia, but being part of the Jewish community was an added bonus. It was very special.” ■