When Seamas Brian McClafferty left high school at 17, it was to enter a Franciscan seminary in New York. “I had never left Nova Scotia, or Annapolis Royal, my hometown with 600 people,” he recalls. “New York shocked me. On the way to the seminary, we stopped at a light across from a building with big glass windows on which were emblazoned gold letters. I experienced a powerful emotional reaction. I asked my neighbor, a New Yorker, what was on the window. Oh, he said, that’s just Hebrew. I knew immediately that I had to learn about these letters. By the time that first year ended, I had acquired the nickname ‘Rabbi,’ because of my interest in things Jewish, especially letters.

“In the second year – a cloistered year of silence and meditation – one of the priests brought a model Torah Scroll and showed me how to write some Hebrew letters. I still have the piece of paper with his writing on it. I also discovered that Webster’s Dictionary had a copy of the Hebrew alphabet, through which I taught myself the Hebrew letters. I then discovered tapes for learning Hebrew and learned to say simple phrases like, ‘Is this the last bus?’

“Ultimately, when I left the seminary and went through the so-called ‘crisis’ that led me to leave the church, I began to consider my religious status. I discussed it with a Jewish friend and he said: ‘You sound more Jewish than me. I’m surprised that you never converted!’ At 24, I decided to do it.”

“Ultimately, when I left the seminary and went through the so-called ‘crisis’ that led me to leave the church, I began to consider my religious status. I discussed it with a Jewish friend and he said: ‘You sound more Jewish than me. I’m surprised that you never converted!’ At 24, I decided to do it.”

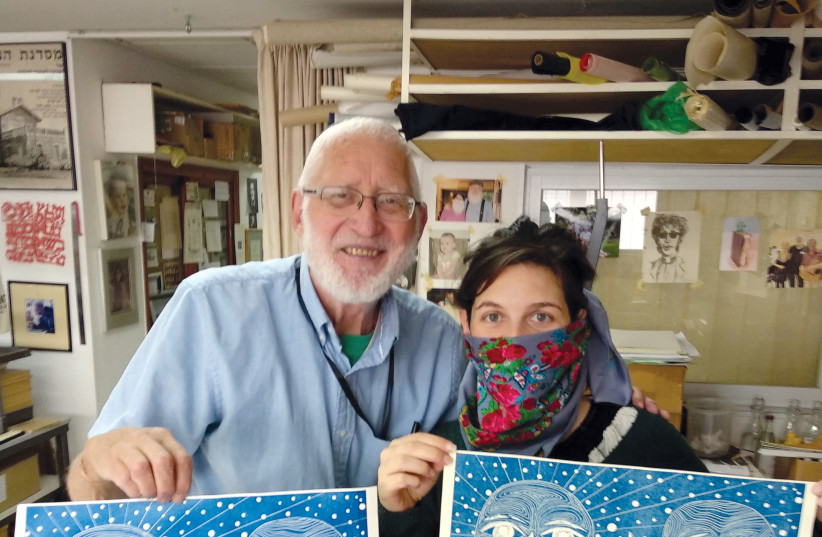

Yehuda Miklaf

From that decision – which took some years to fulfill – to becoming a Hebrew printer was still some ways off.

“Fine printing in Hebrew is very limited. Few people, here or abroad, are involved. Nevertheless I was driven by a desire to pursue this quest for printing in Hebrew. Oddly enough I discovered that my own family background had prepared me for such a task.

“My grandmother had a lending library in her house. She used to loan books for two cents a day. People would read a book and return the next day for more. My grandmother inspired them; she also loved the social aspect of her work. The ladies would pop in to change their books and she thus got to know all the news. She located this library in her house and ours. So I grew up surrounded by books.

“At age 13, I was employed to look after the furnace in the public library. I’d start the fire and stay an hour reading, morning and evening. Later, when I was working at the main library at the University of Toronto, I used to spend lunch hour roaming through the book stacks, and got a feeling about type, book bindings and design.

“I was a library technician, but I wanted to print. What I didn’t know was that I was surrounded by closet printers. A lot of the staff had printing presses in their basements at home and printed at night.”

Despairing of entering the world of printing, Yehuda Miklaf (the name in Hebrew means ‘from parchment’) took courses in bookbinding, a closely related profession. Initially, he became so involved in bookbinding that he had no time for printing.

“I was in awe of printers. There was one guy, an American exile, a draft-dodger. He and his wife had a printing press. They lived in a coach house and ran their printing workshop downstairs. I was overwhelmed by all this equipment.”

Immigrating to Israel

Miklaf immigrated to Israel in 1986. In 1989, when he was living in Jerusalem, he met Gregory Robison, who was living in east Jerusalem with his wife. Robison had popped into the Jerusalem Print Workshop – the national center for fine art printers – looking for handmade paper and was told to look up Miklaf.

“We hit it off immediately,” recalls Miklaf. “I went to his place and did some printing on his press, which I thought was fantastic. Through Nelly Stavisky, another local book arts person, I acquired an old printing press that she had salvaged from the Old City. Then the director of the Jerusalem Print Workshop, Arik Kilemnik, offered me a printing press he had no place for. That was the beginning of Shalom Yehuda Press.”

If some of the circumstances that helped Miklaf on his way seem fortuitous, others ended in frustration. His friend Robison, a Catholic, was friendly with the local Franciscan printing press. He took Miklaf there, and he was able to buy equipment from them. “The Franciscan Printing Press was founded in 1840, and they still had most of the original printing presses and types, all kept in pristine condition and organized in a way that would put a regular printing shop to shame.”

While getting into printing, Miklaf also stumbled across the historical antecedents of the private press in Israel. As a bookbinder, for example, he needed Hebrew type to title books. “A friend of mine, Victor Navon, knew of a type foundry in Jerusalem’s Beit Yisrael neighborhood. When he went there, he met the owner’s son, who had come to empty out the shop since his father could no longer work. Victor immediately brought me over and the son offered me the equipment for $10,000. I told him I was only interested in saving it so that it was not destroyed. ‘In that case,’ he said, ‘you can have it for $2,000, because I promised my father that I’d look for a place to save it.’”

The first Hebrew typefaces that Miklaf inherited were in fact among the only ones to have been created locally in pre-state Palestine, originally by Dr. Moshe Spitzer (d. 1982), and then given over to the man from whom Miklaf ultimately received them.

“When Dr. Spitzer came to Palestine from Germany and wanted to print, he couldn’t find any type, so he brought in someone from Spain to make the matrices, and then appointed a manager from England to run the German-made machinery. These matrices were cottage-industry level, not commercial but usable. They produced almost all the Hebrew type to the end of the technology. Eventually, the line-casting machines took over, then film and then computer. So this technology more or less died a natural death.”

Miklaf had no place to store the machines and matrices, so through his friend, Tova Sheintuch, he had them donated to the National Library.

“The first full text I printed in Hebrew was ‘The Crystal Goblet,’ an essay about printing by Beatrice Warde, translated by Dr. Spitzer for the Israel Bibliophile Society but never published. Warde wrote this famous essay subtitled ‘Printing Should be Invisible.’ The idea is that when you pick up a piece of text your eye should immediately want to read it effortlessly, without stopping to admire the typeface.

“Prior to that, I’d printed a quote from Psalm 48. This was for Gregory, for whom I made a sketch book about ‘walking about Zion and counting her towers,’ because he used to walk around a lot and sketch in Jerusalem. I did it in Hadassah. This font was designed by Henry Friedlander, whom I met just before he passed away. He looked at me and said: ‘What are you doing this for? This is madness! Setting type by hand.’ I told him how I loved it, and wanted to save the technology. He was quite abrupt: ‘If I were your age, I’d get a computer!’”

Another problem constantly facing Miklaf was finding appropriate matching typefaces for printing English and Hebrew on the same document: “I remember Ariel Wardi, an Israeli printmaker, asking me why I thought Hadassah (Hebrew) went with Folio (English). All I could reply was because they were the only faces I owned at the time!”

Miklaf’s next major step was to enter the world of artists’ books (livres d’artistes). “Gary Goldstein, who specializes in altered books, was at an artists’ book conference in New York and six people told him that if he’s in Jerusalem he should look up Yehuda Miklaf.

“On his return we met and decided to work on a project together. I’d been interested in doing something in the spirit of the music composer, John Cage, who used chance operations to compose music. I thought that what he did with music I could do with a book. I took one of the stories I’d heard from him and printed about 16 copies. I gave a proof copy to Gary who drew around my words. I made plates from these drawings and printed the drawings on the other books. He then colored them by hand, each one slightly differently. This, of course, was all in English. I wanted to present one of the copies to John Cage when I was in New York. But he passed away while I was still binding the book. So I didn’t get to see him. But I did a broadside with a linoleum cut of him, using a quote of his in Hebrew and English. The broadside illustrates one way of solving the problem of using English and Hebrew typefaces together. Here I simply separated the two with the graphic, in order not to juxtapose them.

“I then wanted to do some miniature dual-language books. My friend Victor gave me a bunch of typefaces, one of which was a superb tiny Frank Ruehl. I sent the result to an international miniature book exhibition and won first prize for my binding. I printed two images, varied their size, and made linoleum cuts of them, and printed them randomly on the pages. In one case the word ‘parpar’ (Hebrew for butterfly) appeared next to an image of a butterfly.”

One of Miklaf’s more recent projects was a bibliophiles’ version of Yitzhak Navon’s Six Days and Seven Gates, written by the late president of Israel. This presented another problem.

“This book needed to be printed in Hebrew with vowels. I had no metal faces with vowels, so I began playing around on the computer, and as a sample I did a poem by a friend of mine, where I did the text on the computer and had it transferred to a photo-polymer plate, setting the colophon and title page by hand since there are no vowels. Using photo-polymer plates is for me a concession. I prefer metal types, and setting by hand.”

Today in his spacious studio in the capital’s Talpiot industrial district, Miklaf is busy printing limited edition Hebrew texts and binding books, often one-offs, for a worldwide clientele.

Miklaf is a member of the Israeli Masonic Lodge for which he has executed a number of projects. One was a binding that included a copy of the complete Hebrew Bible, the Christian Bible and the Koran. This is an expression of the Masonic idea of an all-encompassing spirituality that is inclusive rather than exclusive. “We place this on the table,” he explains “when we are having a masonic meeting.” In the same spirit, he designed another binding for the all-important register of the Masonic Lodge.

Another recent book he did was with Andi Arnovitz, one of a number of collaborations he has undertaken with other artists. This book is on the history of sound. Arnovitz provided the watercolors that Miklaf embedded in each page.

Being a Canadian by birth, Miklaf has many friends in the old country. One book dealer in Toronto is David Mason. “He wrote his memoirs, which he called The Pope’s Bookbinder, because he once bound something that was given to the pope. So what I designed for the book cover was his store with bookshelves and his sign, and the pope looking at them, as well as the cat that was always with him. All the design was from leather. It was in a show in England and in the catalogue, and a collector in New York saw it and called me to say he wanted to buy it. I told him that it belonged to David. ‘In that case,’ he said, ‘I want you to do a book exactly like that for me.’ Since he collected miniature books, I showed him his collection, and managed to print his picture onto a piece of leather.

“I had another friend in Toronto, Richard Landon, who was the chief librarian of the Rare Book Library. He was a very fine man, who unfortunately passed away recently. His widow saw the book I had done for David Mason, who was a friend of his. She sent me a copy of Richard’s essays to bind. This used about 5,000 pieces of leather!” Miklaf’s binding shows these miniatures, and this is what visitors see when they walk into that library.

Miklaf has also been very close to paper-makers in Israel and for whom he is producing a book with samples from 11 Israeli paper-makers. Begun when Shalom Yehuda Press was new, it has taken years to produce and has become a memorial to Joyce Schmidt, who brought the technology of handmade paper to Israel.

“There was a project of the magazine Hand Papermaking. The project was called ‘Letterpress printing on handmade paper.’ I knew I had to be in it. So I wrote to them and said I will print on mitnan paper, which is made only in Israel, and in Aramaic – if you will let me in. I knew Natan Kaaren, a paper-maker from kibbutz Sde Yoav, who was in Italy at the time. I got in touch with him and told him that I needed 150 sheets of mitnan paper. He said it was no problem, and he would produce the sheets on kibbutz. He came back to Israel with his new wife and together they made these papers. Then I took a piece of my marbled paper (which he not only makes, but ran a number of classes on it - MB), transferred it to lino, cut it out, and placed the skull in it to illustrate the Aramaic in the philosophical, rabbinic work Pirkei Avot 2:7, which states: ‘He saw a skull floating on the water and said to it, “because you drowned others they drowned you, and those who drowned you will eventually be drowned.”’ I put in the text and sent it into the project. Thankfully, they accepted it.”

Although he has retired from his public work, Miklaf continues to create works that appeal to him.

“A few months ago I got to bind a Soncino Torah from the Soncino Press. This was produced by the Gesellschaft für die Jiddische Bücher in Berlin in 1932. This Gesellschaft intended to produce very fine quality Jewish books. They produced this one and then they were disbanded by the Nazis. It’s an absolutely gorgeous book. They did seven of the editions on parchment. Dr. Lila Avrin, a professor of the history of the Hebrew book, said it was the most beautiful Jewish book ever printed. Soncino (the oldest established printers going back to the 15th century in Italy) used their own font for the printing.”

Miklaf also worked on binding David Moss’s Haggadah, one of the most famous Jewish books of the last half-century. Miklaf had bound the original copy, which went to Benjamin Levy, who had commissioned it. Moss then asked for three similar bindings on the facsimile edition. “I bound the three copies for which I had to press my handmade embossing tool 15,000 times, all in one week. I ended up inventing a tool that controlled the temperature because you normally heat the tool (I use a Bunsen burner), and then put it on a wet pad until it stops sizzling.”

This tool was also used when he was asked to create a binding for a Nano-Bible for Pope Benedict XVI when he visited Israel in 2014. The Bible is miniscule – the entire text is written on a single chip and cannot be seen by the naked eye. It was presented to the pope by Shimon Peres, Israel’s then-president.

“When the news got around that I had made the box, one of my friends suggested that I write a short note inside explaining that it was made by the ‘former Brother Innocent of the Franciscan Order.’ Since I had been told not to talk to anyone in the media about the project, I suspected – not seriously though – that they were afraid that my past might make it into the story!

“Later on, my wife, Maurene, and I went to the Technion in Haifa. We were treated like royalty. The people who greeted us were in awe. But even there we were somewhat disappointed. They had made a vitrine, which when we were there was being repaired. So we couldn’t actually see the box that I had so carefully designed. But it wasn’t too bad. I told them I’d seen it already!”

Although he started his career wanting to print Hebrew, Miklaf took a number of print-related turns to produce an impressive body of work that includes book-binding, miniature books, marbling end papers, and wonderful co-operative projects with other artists. Even now he may still surprise us with his apparently endless creative output. ■