Daniel was a very angry man on that summer day as he sat at his desk in the small Jerusalem apartment on Metudela Street that he had shared with his girlfriend until recently. The anger almost popped out at you when you read the document he wrote, which was in fact his last will and testament

Not that Daniel felt that he was going to die any time soon. At the age of 24, he had just completed his degree at the Hebrew University and was eager to enter the workforce in his chosen field. He had no intention of dying.

But what he did intend was to write a will leaving Rena, his girlfriend and partner for quite some time, clearly out of his will. Not only was he going to leave her out of the will, but he was determined to ensure that the baby she was carrying would not in the fullness of time inherit a single lira (this was well before the lira was replaced in 1980 by the shekel as Israel’s currency).

They had met in the lecture halls of the Hebrew University and had been living together for two years. There was no talk of marriage even that far back in those far more conservative years. After all, they were young and were students, and the world’s responsibilities did not weigh too heavily on them.

Imagine, then, his shock when Rena, over a hurried breakfast as she was about to head out to her final exam, told him that they really should get married immediately after the exam results were posted.

“You think?” He raised his eyebrows in some surprise. “What’s wrong with the present arrangement?”

“Can’t carry on like this forever,” she replied. “After the exams, we will be entering the real world.” Her distinct emphasis on the word “real” did not escape him. It was as if she was putting down all their romance of the previous two years as some kind of fantasy, and that began to irritate him.

He stared at her.

“And anyway,” she added, collecting her satchel and putting on the cute little beret of which he was so fond, “it’s about time we became responsible. Also you should know, Daniel, that I am three months pregnant.”

His irritation had now morphed into total astonishment. “But we agreed –”

“– that I wouldn’t get pregnant,” she finished the sentence for him.”But I have now changed my mind. It’s my right. I would like to become a mother, so let’s try to take life together as a couple far more seriously.” She had a hand on the latch of the door and swung it open while giving him one of her irresistible smiles. “You will love being a father. Let’s talk about it when we both come back from our exams this evening.” And without saying more, she fairly danced out of the doorway and shut the door behind her, leaving him dumbfounded, still holding the coffee cup halfway between the tabletop and his lips.

After a few moments, Daniel set down the cup. He gave the matter a lot of thought for the next hour or so. And then, with the decisiveness that characterized him already, despite his young age, which would be a hallmark of his later successful business career, which was the main reason for the substantial estate that he left after he died, he stood up, collected his sparse student belongings and put them in a backpack. He then tore two pages out of an exercise book and sat down to write two documents.

Breaking up with his girlfriend and leaving her out of his will

The first was a simple letter of goodbye to Rena. Their relationship was over, he wrote, and although he wished her well, he intended to never see her again. He made no mention of the child that she was possibly carrying. He signed the letter and stuck it with some Sellotape to the fridge in the kitchen, where it could not be missed.

He then returned to the table and wrote what turned out to be a momentous document which decades later roiled the legal fraternity in Israel and, in particular, those of us who are deeply involved in day-to-day issues of inheritance and probate.

For in this letter, Daniel made clear that he was leaving nothing to Rena. He was also clear that everything that he ever owned would be passed on after his death to his younger brothers and sister. At that time, his entire estate consisted of a couple of pairs of faded jeans and a few T-shirts. But his wealth would be very different – and significantly large – when this will came up before the courts sixty years later.

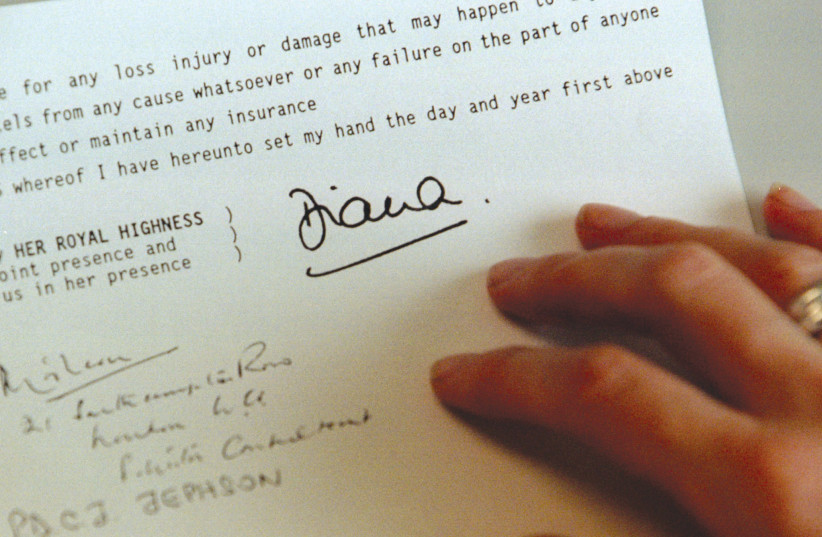

Sitting in that summer’s late afternoon on Metudela Street, he reviewed the document, was satisfied. With that, he signed the handwritten exercise book page, dated it, folded it and put it in an envelope, which he took with him as he left the apartment for good.

Daniel then made his way to the center of town, into the busy traffic-jammed Ben-Yehuda Street. (This was years before Ben-Yehuda would became a pedestrian-only street). He rented a furnished room above one of the cafes on the street and put the envelope with the handwritten will in the center drawer of the night table next to the bed.

It was years before Daniel met up with his past.

In the interim, Rena had given birth and Daniel found out, to his dismay, that even though their child was born out of wedlock, he was responsible for the child’s support and maintenance. A long and bitter fight ensued in the courts, and those were the only times that he saw Rena again. Rena argued that apart from child support and assistance in renting an apartment for her and the child, she herself deserved a certain part of Daniel’s slowly acquired burgeoning reputation in his field. She claimed that Daniel’s university degrees and thus his career was underpinned by the fact that she had supported him during his studies. Daniel contested this vigorously, saying that neither he nor she supported each other and proved that they both worked in order to support themselves through university. After about a year of debates and several hearings, the court agreed with him, and Rena received nothing.

It was, however, very different when it came to the claim for child support. The court and, for that matter, Jewish law do not differentiate between a child born in wedlock or out of wedlock, with benefit of clergy or without benefit of clergy. The court determined that the child was his (not a simple determination, as this was well before the availability of DNA tests, which today are common and conclusive). A level of maintenance linked to the cost of living index was determined by the court. Daniel gave a standing order to his bank, which paid the sum monthly, and he never sought to see Rena or the child ever again. All Rena’s attempts to see him failed.

Daniel never married, although over the years he had formed a relationship which became very long term and continued until his death.

Meeting his biological son for the first time

It was only much later that Daniel’s familial situation began to change. This was when his partner, Ofra, opened the front door to a young man in army uniform. The young man identified himself to Daniel as his son. He was about to finish his army service, he told Daniel, and he decided to find out just who was his biological father.

Astonishingly, this first meeting between father and son went extraordinarily well. The father found the son, Raphael, to be charming, personable and a eminently likable. The son, in his turn, had found his long-lost father, and a bonding was authentic and strong.

For the next 20 years, the relationship between father and son and Ofra blossomed, not least after Raphael got married, and Daniel and Ofra attended the wedding. Rena was also there, but both sides kept to the extreme ends of the wedding hall and thus never encountered each other face to face. When grandchildren arrived, Daniel’s joy was complete. The family spent holidays together with the children, and Ofra became a surrogate grandmother to the grandchildren.

When Daniel died sixty years almost to the day after he wrote that momentous will in the small apartment on Metudela Street, the whole family sat shiva. Ofra, Raphael, and Daniel’s younger brothers and sister sat together. After the shiva was over, Raphael and Ofra went through Daniel’s papers. In an obscure file tucked away behind dusty books in the library, they found a paper folder in which were several legal documents – among them the will that Daniel had made six decades earlier.

Finding the will

It is, of course, a criminal offense to hide a will, so the will was put in for probate almost immediately. At the same time, Raphael submitted a formal objection, asking the court to declare null and void the will’s instructions to leave all Daniel’s assets to his brothers and sister.

Raphael’s lawyer’s main goal was try to persuade the family law court that inasmuch as Daniel had obviously forgotten about this will which had been written so long before, it did not reflect the true wishes of the deceased.

“Clearly,” the lawyer to stated to the judge “if Daniel had remembered that he had made this will, he would have changed it to ensure that his only son would inherit.”

“Clearly, if Daniel had remembered that he had made this will, he would have changed it to ensure that his only son would inherit.”“if Daniel had remembered that he had made this will, he would have changed it to ensure that his only son would inherit.”

Raphael's lawyer

Daniel’s siblings also expressed their astonishment that there was no will taking care of Daniel’s only son. However, that did not detract from their lawyers’ claiming that the very substantial inheritance was, by virtue of the words written 60 years back, to be given to the brothers and sister.

“There is no other will; therefore, this is the will that must stand.“

The famous old legal adage dating back to the days of the Mishna was recited – drilled – before the judge: “It is incumbent upon us to fulfill the wishes of the deceased.”

Raphael argued that due to the family’s close emotional bonding over the recent decades, it was clear that Daniel had forgotten the will, and his wishes in the present day circumstances had changed.

The judge was sympathetic. She pointed out that the wishes of the deceased were obviously different from those stated in the will. Life had changed for Daniel when his only son appeared, and then delivered the precious grandchildren. The judge pointed out the joint holidays, celebrations of family events together, and the genuinely warm relationship with Daniel’s significant other, Ofra. This, stated the judge, demonstrated beyond doubt that Daniel’s “actual intention” was “not what was written” in the will of six decades earlier which was written “under the disappointment which the deceased then felt, whether rightly or wrongly, with regard to Raphael’s mother.”

The family law court voided the will and pronounced Raphael the sole heir.

But the brothers and sister were not going to go so easily. Daniel had amassed a substantial estate over the years and, as their lawyers claimed, “It is not a question of sentimentality or emotions but will. And the words in that will are plain and clear: ”The brothers and sister, and only they, were the inheritors of Daniel’s estate.”

The siblings appealed the family law court’s ruling to the district court. In the district court, the appeal was heard before three judges. In a very similar case (the facts were different, but the legal premises were the same), Judge Naftali Shiloh – widely recognized as one of the eminent interpreters of Israeli inheritance law – disagreed totally with the lower court.

“The will is a will is a will,” the court declared. “And it is what it is. Not what we would like it to be or what in our eyes it should be. It is not up to us as judges to create wills, guessing or inferring what the deceased’s wishes would be at the time of their death. People who make wills have every right to change them whenever they want. And when they don’t do so, the will that they wrote last is not abrogated and remains valid until the day they die.”

Judge Shilo also took issue with the question of whether the will was, in fact, forgotten. He pointed out that in the case before him, the will was kept with other legal documents, albeit in some side shelf. “But even if the question of forgetting was proven, said the judge, “we have no right to inject our own sense of what is right and what is becoming and what is emotionally comforting for us in light of the present-day circumstances. The will is a formal document, and it absolutely rules the legal situation.”

Raphael’s lawyers pointed out that there was a proposal laid on before the Israeli legislature – the Knesset – in which the proposing MK suggested that the law should be changed so that if a will had been made and had not been changed or ratified within 15 years, the court could, in fact, cancel it.

But Judge Shiloh was left unimpressed and pointed out that this proposal was far from being agreed upon and had not even been debated in the Knesset. It was just a proposal, the court averred, and it was far from being legislated; therefore, in real terms, it was at that point meaningless.

The judge cited another famous case where a couple has requested that their lawyers prepare a will for them both. The husband and wife had discussed details with their lawyer and gave him precise instructions about what they wanted to put in their will. The lawyer’s office did indeed draw up the will with the conditions that they wanted to see enshrined in the document. However, the couple were both killed in a car accident on the way to the signing at the lawyer’s office. Their wishes were crystal clear, yet the will is a formal document which, without a signature, was not executed and thus was not recognized in an ensuing dispute.

Daniel’s case, which was decided about a month ago in the district court, caused an uproar in the inheritance legal circles. We are now waiting with bated breath to see whether the decision by the district court will be appealed to the Supreme Court and which direction that final court will take in regard to such a forgotten will. ■

Dr. Haim Katz and Adv. Sam Katz are senior partners in a law firm based in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Their new book in English, The Complete Guide to Wills and Inheritance in Israel, is published by Israel Legal Publications. Specializing in family law and inheritance disputes, they serve on the Israel Bar Association National Committee for Inheritance Law, which advises the government on law reform relating to inheritance.

office@drkatzlaw.com