In many Orthodox communities, it is standard practice for a woman to begin to cover her hair once she is married. It is interesting to note, however, that there is a wide range of ways in which this is accomplished.

In Orthodox communities where this is practiced, the range of hair covering apparel varies tremendously. It can include colorful headbands, baseball caps, fedoras, various-sized scarves, large hats and human hair wigs that cover some or all of the hair. There are communities where women wear wigs and a second head covering, and in some Hassidic communities, women shave their hair and wear a kerchief or wig over their bald heads. At the same time, a sizable minority of observant women do not cover their hair at all outside of religious settings, such as synagogues or when lighting Shabbat candles.

This topic, touching as it does on identity, femininity, sexuality and modesty, is a matter of no small import, and many women seek to make this practice their own through textual study and independent decision making.

People often wonder if the practice is biblically based or rabbinically mandated.

The background

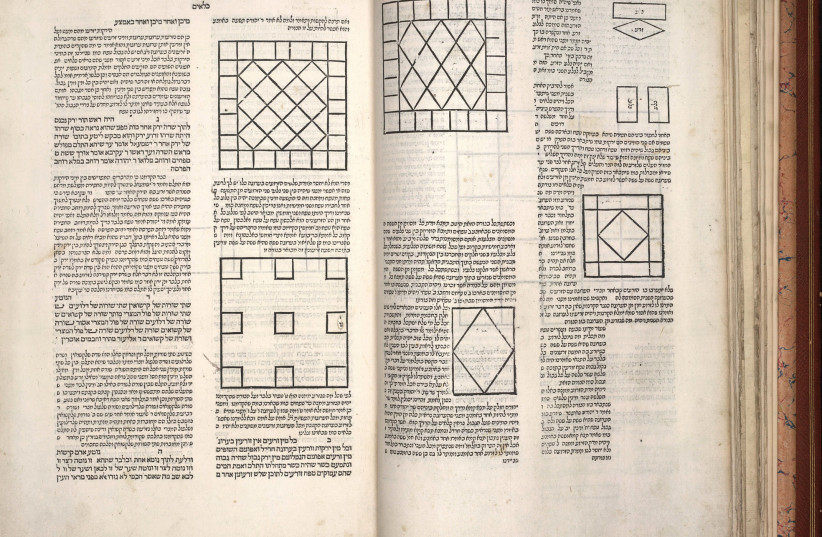

The classic Mishnah that relates to head coverings is in Ketubot 7:6, “The following are to be divorced without receiving their ketubah: A wife who violates dat moshe or dat yehudit (Jewish practice). ...What is [considered to be a violation of] dat yehudit? Going out with her head uncovered...”

In this Mishnaic passage, the text introduces examples of offensive behavior on the part of the wife that gives legitimate cause to her husband to divorce her without paying her ketubah. There are two categories related to her possible impropriety that are presented. The first is termed dat moshe and the second dat yehudit.

The consequences for the violation of either are specific to a married woman, leading to divorce and forfeit of her ketubah. The Mishnah presents four examples that illustrate violations of dat moshe: Feeding her husband untithed food, having relations with her husband when she is a niddah, neglecting to separate the challah portion of the household dough and taking vows without fulfilling them. These four examples have direct implications for the husband and are grounds for divorce.

Conspicuously absent are violations of severe biblical prohibitions, such as desecrating Shabbat, eating non-kosher food or thievery. In other words, her transgression of biblical law, if it only affects her, does not cause her to forfeit her ketubah. The forfeiture is only exercised when she violates this typology of dat moshe, and in doing so, causes her husband to sin.

THE MISHNAH then presents a second category of behavior termed dat yehudit. While the behavior described as violations of dat yehudit does not seem to involve the transgression of explicit Torah commandments, it is consequential to license a man divorcing his wife without paying her ketubah. Included in the list are a woman going out with her head bare, spinning in the marketplace and talking to men.

A parallel Tosefta in Ketubot adds several other examples: Going out with clothing open on both sides, baring arms, coarse familiarity with servants and bathing with everyone [men and women] in the bathhouse. In violating either dat moshe or dat yehudit, loss of ketubah serves as a severe penalty and clearly was meant to be a significant deterrent to all of the behaviors cited in the Mishnah.

The Talmud raises a question about the categorization of a married woman covering her head as a requirement of dat yehudit, under the assumption that it refers to a non-biblical obligation. In its ensuing discussion of the Mishnah, the Talmud asserts unequivocally that going out bareheaded violates biblical law.

In Ketubot 72a, it states, “And who is considered a woman who violates dat yehudit? One who goes out and her head is uncovered.”

The Talmud asks, “The prohibition against a woman going out with her head uncovered is not merely a custom of Jewish women. Rather, it is by Torah law, as it is written, ‘And he shall uncover the head of the woman’” (Numbers 5:18).

The biblical verse cited as textual support for hair coverings is found in the Talmud in the context of a woman accused by her husband of adultery without the support of witnesses. In rabbinic texts, such a woman is referred to as a sotah (one who goes astray) and this is the common term used to reference the biblical text, as well. There is no certain way to determine whether this woman has sinned or whether her husband has been overcome by jealousy. Given the severity of the accusation and the lack of evidence, the woman is brought before the High Priest to undergo a ritual that will establish her guilt or her innocence. One of the steps involves a ritual that uncovers her head or dishevels her hair.

“After he has made the woman stand before the Lord, the priest shall uncover/dishevel/unbind the woman’s head and place upon her hands the meal offering of remembrance, which is a meal offering of jealousy. And in the priest’s hands shall be the water of bitterness that induces the spell.”

Numbers 5:18

In Numbers 5:18, it says, “After he has made the woman stand before the Lord, the priest shall uncover/dishevel/unbind the woman’s head and place upon her hands the meal offering of remembrance, which is a meal offering of jealousy. And in the priest’s hands shall be the water of bitterness that induces the spell.”

In the next column, we will undertake an analysis of the ambiguous meaning of the biblical word p’ra and continue to trace the evolution of women’s head covering from the biblical text about the sotah to the more practical halakhic discourse in the Talmud. ■

The writer teaches contemporary Halacha at the Matan Advanced Talmud Institute. She also teaches Talmud at the Pardes Institute, along with courses on sexuality and sanctity in the Jewish tradition.