The great 4th-century Talmudic sage Rava had a dream in which he saw that his mansion had collapsed and people came and took away the bricks one by one.

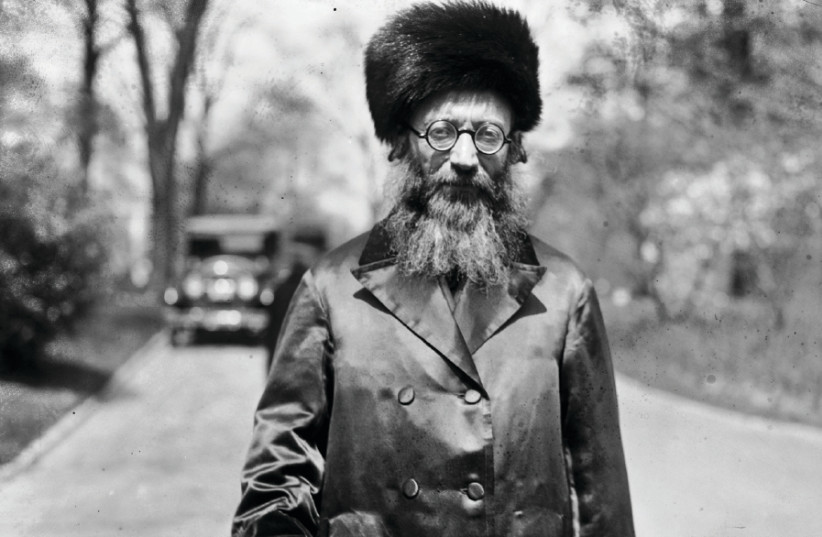

Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook attributed great metaphorical significance to this dream. He explained that Rava had a system of thought in which all the particulars of that system fit together, “just as the parts of a building relate to the structure as a whole.” However, people of lesser stature failed to recognize “how all these specifics flow from the general theory and how they are interrelated.”

In The Souls of the World of Chaos, his recently published translation and exploration of Rav Kook’s short essay, Rabbi Bezalel Naor uses Rav Kook’s interpretation of Rava’s dream to explain the bifurcated state of the study of Rav Kook himself.

“Various students grab pieces of the Nachlass [manuscripts, etc.], while the Gestalt of the great man’s teaching disappears beyond the horizon.”

Rav Kook saw this inability of the narrow-minded to appreciate the relationship between the proverbial trees and the forest as a broad phenomenon.

“So for the generation, there is no ‘mansion’ here, no palace of wisdom, but rather brick by brick, a collection of opinions, laws, and ethics that all appreciate though they do not recognize their value as parts of the palace… Each lovingly grabs a piece, though by doing so, one is unable to encompass the overall theory that produced this specific.”

This inability of the small-minded to grasp the larger picture lies at the heart of The Souls of the World of Chaos. As Rabbi Naor explains, this short pensée seeks to explain the phenomenon of “the soul of the Second Aliyah, the second wave of immigration to the Land of Israel in modern times. Typically the founders of the kibbutz movement were young Russian Jews who espoused ideals of Socialism while rebelling against the traditional Jewish lifestyle and mores.”

Nothing to fear from the radical socialists

The iconoclasm and radicalism of these youth terrified many of Rav Kook’s traditionalist peers. Yet Rav Kook insists, “There is nothing to fear; only sinners, weak souls, and flatterers fear and tremble. But the mighty in strength know that this show of strength is one of the visions that comes for the need of perfecting the world…” Rav Kook saw the secularizing intellectual and cultural trends of his time as part and parcel of a larger cosmic drama.

Rav Kook goes so far as to claim that these “souls of chaos are higher than souls of establishment.”

It is their longing for freedom and infinitude that leads them to scoff at convention and limitations. They herald “a new and wonderful creative existence; on the verge of the expansion of borders; before the birth of a law that is above laws.”

Rabbi Naor explains that for Rav Kook, the rejection of conventional morality by the youth of the Second Aliyah “consists of a longing for a higher morality, an autonomous morality, as opposed to one enforced by religious coercion.”

The Souls of the World of Chaos is one of the crescendos in Rav Kook’s tendency to see sparks of righteousness and holiness among the segments of the Jewish people who largely rejected his religious worldview.

Rav Kook could see the secular Zionist pioneers as dangerous and misguided – and yet still guided by the hand of providence.

Rabbi Naor points to this essay’s contemporary relevance, noting that “this essay is of perennial value and continues to resonate throughout the ages, whenever there is a concerted breakdown of the established order and a new world order, yet hazy and ill-defined, looms on the horizon.”

Indeed, at this moment when so much of our world has become hyperpolarized and caught up in internecine culture wars, Rav Kook’s writings challenge us to seek out the positive in opposing camps.

Much of Naor’s contribution in this volume is the excavation of the layers of Kabbalistic thought upon which Rav Kook’s approach is built.

After a short introduction to the essay and his translation, Naor includes seven appendices picking up on themes connected to the text. These appendices and his copious endnotes are a treasure trove of textual and intellectual archaeology. However, they require a very high level of proficiency in Kabbalistic jargon and literature to be fully appreciated. Moreover, this reader would have appreciated a more explicit uncovering of the relationship between the fine points of scholarship and their relevance to the essay itself.

The volume also includes two book reviews: the first an intellectual biography of Rav Kook’s early years, and the second a collection of Rav Kook’s son R. Zvi Yehuda Kook’s letters.

In the latter review, Naor shares an anecdote that drives home Rav Kook’s expansive tendencies. Upon Naor’s first encounter with Rabbi Tzvi Yehuda Kook, he opened by saying, ‘How much your father loved the Jewish people!’ R. Zvi Yehuda reacted with hearty laughter. “‘Love of Israel?’ My father loved the whole world, even zome’ah (the vegetable kingdom), even domem (the mineral kingdom)!”

At a time when so many of us can only cast aspersions on our ideological opponents, Rabbi Naor has shone a welcome light on a classic text that provides a richer, more complex model of critique and appreciation. <

The Souls of the World of Chaos

By Rabbi Abraham Isaac Hakohen Kook and Rabbi Bezalel Naor

Kodesh Press

224 pages; $24.95