“The Arnold and Deanne Collection of Early American Judaica may well be the finest private collection of its kind ever assembled,” wrote the noted professor of American Jewish history Jonathan Sarna. This is the introductory sentence in his essay “Marking Time” in the Constellations of Atlantic Jewish History 1555-1890: The Arnold and Deanne Collection of Early American Judaica volume. The collection is housed at the University of Pennsylvania.

Sarna points to the uniqueness of what the Kaplans have done. “Their collection, as a result, highlights wide-ranging facets of early American Jewish life, embracing social, political, economic, cultural, and religious history.”

The Kaplans continue to add to the collection, which today has grown to 13,000 objects – paper and items of all types – and soon it will all be digitized. I met this special couple for the first time in 2003; we have met a few more times since my wife and I returned to Israel. My last words when visiting their home in Florida: I promised that I would see them again. In 2022, my son and I were in the US, and I kept my promise.

While visiting family in Florida, we made a special trip to see the Kaplans in their home north of Sarasota. What a wonderful reunion. They were, just as I recalled, always collecting.

A few minutes after we arrived, Arnold began to show me and my family members accompanying me new finds – documents and objects to be transported to a special permanent home at the University of Pennsylvania. I felt renewed seeing this couple – most unusual, dedicated, and philanthropic individuals.

In 2024, a Jewish and secular leap year, I decided it was an opportunity to focus on a few of the Passover-related objects in their collection.

The Kaplan Collection's Passover items

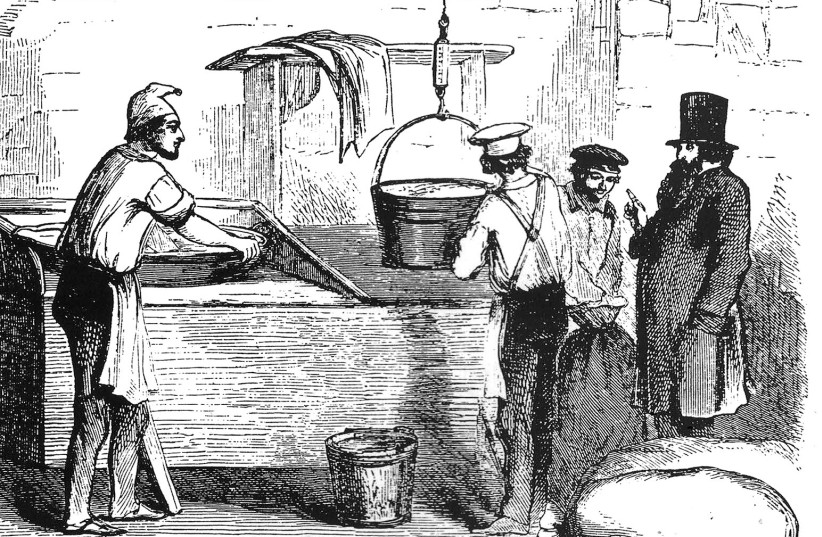

Making matzah was a delicate art in the 1850s, the decade before the Civil War. S.R. Cohen, located at the corner of Pike and Cherry streets in New York City, advertised in the weekly newspaper The Asmonean. The ad was illustrated with a drawing showing matzah being baked and produced in a matzah machine Cohen had made. In 1858, Doesticks – the pseudonym of the once-famed journalist and humorist Mortimer Neal Thomson – wrote a descriptive story titled “The Matzah Process,” which was illustrated for Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Surrounding the text were six images showing how matzah was made, how matzah meal was prepared from cracked matzah, and an image of people with their grocery baskets lined up to buy round matzah.

Sarna quotes from the description in the newspaper pointing to observance of the holiday with “punctillious exactitude by all, old and young, no matter how rich or poor.” The matzah bakeries were situated in non-Jewish bakeries that Jews leased and transformed for Passover use.

“Every part of the machine that touches the bread is taken out, and others substituted that have never been used for anything else. Thus separate rollers, feeding web, cutters, and other parts of the mechanism are owned by Jews, who put them into machine duty once a year when the feast of the Passover approaches. All this preparation is under the supervision of a rabbi.”

Sarna details some of the process found in the 1858 article. “Matzah-baking had already been mechanized so the matzah was baked, by steam, more quickly and the per pound price was reduced. I particularly like the drawing of a worker riding and pressing the dough into a flat form, where matzah is cut out and then baked.

“The illustration makes clear,” Sarna writes, “that matzah was still sold and distributed in the traditional way (much as fresh bread was): Customers picked it up, unboxed, directly from the bakery.” The price of matzah greatly exceeded that of bread; it sold for “eight cents a pound” ($1.94 in current dollars). An interesting point, Sarna adds: “An illustration depicts ‘grinding the broken pieces of matzah, or unleavened bread, into meal,’ the first illustration of the commercial production of matzah meal known to me.”

Finally, “some of them [matzot] are about an eighth of an inch thick,” Doesticks writes, “and are rather slack baked, being a very light color. Another variety is about twice or three times as thick and is baked much browner.” The sale ad shown is of the customers waiting their turn. Sarna explains, through the drawing, how matzah was baked in 1858.

The Arnold and Deanne Kaplan Collection has an original of the first Chicago Haggadah prepared by Rev. H. Liberman in 1879. The Kaplans have only collected American Haggadot, which are much less known. The Liberman Haggadah fits that category because it may be the first Haggadah illustrated by an American. Each of the drawings is unique in its own fashion, though the work of the same artist.

The drawings are black-and-white, with the new buildings, not pyramids, constructed in Egypt by the Jews. I think possibly based on architecture in Chicago.

While the second and third editions in the 1880s soon disappeared, I came to know the volume through the illustration in the Bank of America Haggadah showing the search for hametz performed by the father and son.

We turn to the noted volume Haggadah and History, which appeared in 1975, as one of volumes published by the Jewish Publication Society to mark the bicentennial of the United States. All the illustrations in the volume are black-and-white. The page from the Chicago Haggadah selected is a family sitting around the Seder table.

“The bearded father looks suitably patriarchal,” the author Prof. Yosef Haim Yerushalmi writes. “The important point to make is that there is only one illustration of an American Jewish father at the Seder drawn by an American artist. The most noted part of the image is the Wicked Son, smoking and flaunting the rest of those at the Seder table, and wearing what are known sartorially as ‘Chicago duds.’”

Yerushalmi continues: “Seated beside the mother, we obviously have the Wise Son, who is engrossed in following the Haggadah, the only son to be wearing a skullcap.” He points out that the “smoking” son is a “mature man raising his hand in a gesture of challenge.” We only see the backs of the other two sons, so you can decide which is which.

Yerushalmi asks an important question: “Did the illustrator intend to hint at the generation gap in the immigrant family?” Certainly a very important observation. The illustrator, whose identity is still unknown, had knowledge of midrashim. In one image, he places baby Moses in the basket on the water.

When you reach the image of baby Moses being saved, it is clearly seen that the midrash on the Book of Exodus is utilized. The arm of the woman, the handmaiden of the daughter of Pharaoh adorned with her crown, extends to bring Moses to the shore.

In the image of the 11 tribes, assuming Levi marched through jointly with another tribe, crossing the Red (Reed) Sea, we see Moses high on the promontory carefully watching his people. The midrash is also brought into use in this image. For the crossing, the tribes were given their own channel, according to the rabbis. The figure of Moses on this high peak reminds me of the famous 1956 film The Ten Commandments. Moses, played by Charlton Heston, is also alone on the mountain watching the masses of his people cross the sea as the Egyptians chase them, and then drown in the sea. In the drawing in the Haggadah, the Egyptian charioteers are blocked as the Israelites cross.

Since this Haggadah has never been reprinted, I decided to reproduce all the drawings in my 1992 American Heritage Haggadah, which I compiled and edited (and is now out of print). We are fortunate that the Kaplan Collection has a copy of the original Haggadah. When it is digitized, people around the world can study it.■