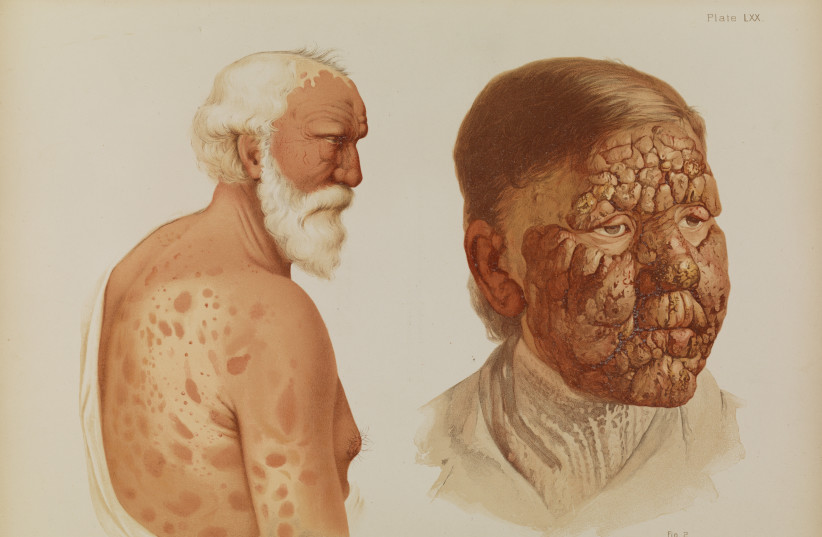

Parashat Tazria deals extensively with tzara’at (a progressive skin disease that can take on many forms). When the Temple stood, a person afflicted with tzara’at would come to the priest, who would determine if the affliction was pure or impure. If it was determined to be impure, the afflicted person would remain outside the camp until enough time passed for him to be pure.

The Talmud reveals that the affliction of tzara’at we learn about in our parasha came as punishment for speaking lashon hara (slander or libel) about another person:

“Reish Lakish says: What is that which is written: ‘This shall be the law of the leper (metzora)?” This means that this shall be the law of a defamer (motzi shem ra).’” (Arachin 15b.)

This saying of Reish Lakish connects with the words of Chazal, who added a different layer to our ordinary understanding of tzara’at. While in the ancient world, tzara’at was a known disease, according to our sages, it was not a natural phenomenon or bodily impurity, but rather it appeared as punishment for speaking ill of others.

The Talmud continues to explain that someone who slanders is punished with tzara’at because he separates people, therefore he should be separated from people.

The Ba’al Shem Tov reveals another layer in the relationship between the sin – lashon hara, and the punishment – tzara’at.

Those who guard their tongue show that they are good to the core. However, those who speak maliciously about others reveal that there is evil inside them. That evil is so strong that it causes them to let it out in the form of speaking badly of others. There are those who are physically sick and those who are spiritually sick. One who speaks badly of others reveals that the soul is ill. It is so full of evil that it leaks out.

Those who see shortcomings in others are actually seeing the shortcomings in themselves, but since they cannot admit it, they seemingly identify them in someone else. Based on this, it is clear that one who speaks badly of someone else is revealing one’s own evil. Therefore, this inner flaw manifests itself as a physical affliction – tzara’at.

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (rabbi of Frankfurt and one of the greatest Jewish thinkers of his generation, 1808-1888) explained the sin and punishment in a different way. The skin is where the person comes in contact with the outside world. Whoever has a problematic and faulty encounter with the outside world– instead of seeing the good, keeps focusing on the bad – becomes afflicted with tzara’at, rot that spreads through the body.

What kind of repair does the Torah suggest for someone who sinned in lashon hara? How can a person be cured of tzara’at?

“If a man has... on the skin of his flesh, and it forms a lesion of tzara’at on the skin of his flesh, he shall be brought to Aaron the priest... The priest shall look at the lesion... the priest shall quarantine the [person with the] lesion... the priest shall pronounce him clean… The priest shall pronounce him unclean...” (Leviticus 13, 2-8)

The kohen is the one who diagnoses tzara’at and is the only one who can cure it. Usually, when someone suffers from an illness, it is a doctor who cures it. The fact that tzara’at was both diagnosed and treated by a kohen teaches us that it was a somatic/spiritual illness. It manifested itself physically in the body, but it was a spiritual person who treated it.

The kohanim, the sons of Aaron, who loved peace and pursued peace, were noted for using the power of speech positively.

Therefore, a person who used his power of speech detrimentally by speaking badly of others is forced to meet the kohen in order to learn from him what is allowed and what is forbidden in speech, what is constructive and what is destructive, and from that to learn to use the power of speech in a positive and constructive manner. ■

The writer is rabbi of the Western Wall and Holy Sites.