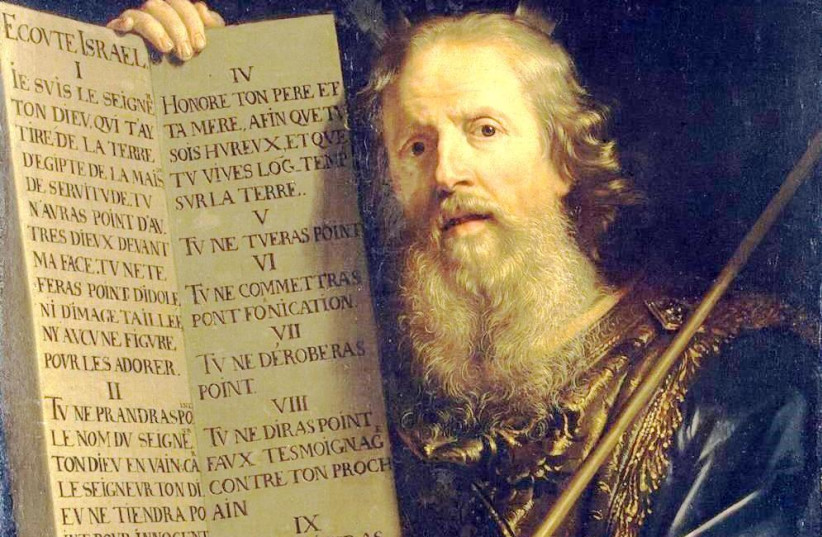

The events at Mount Sinai are among the most dramatic moments in the history of religion. For the first time since creation, God entered the human world and conveyed His will directly.

For thousands of years, human beings tried to discern the presence of God through nature – reading meaning into the heavens, the land, the forces that shape life. Often, that effort went astray. The Creator was exchanged for fragments of creation, and idols took the place of the one God who stands beyond them all.

At Sinai, that search came to an end. God did not need to be inferred or reconstructed: He spoke. Humanity did not struggle upward through speculation: It stood and listened. From that moment on, the course of religious history changed.

A pause before Sinai

However, the dramatic events atop that mountain are recorded in the Torah only after two seemingly ordinary episodes. First, Jethro (Yitro) – Moses’ father-in-law – arrives with Moses’ family. He is received with warmth and honor, welcomed by Moses and the leaders, and invited to a festive meal. It is a gentle story of reunion and hospitality, all the more striking given the strain and uncertainty of desert life. Still, it is hard to see what this scene has to do with the revelation of Torah on a trembling mountain.

Immediately afterward, the Torah turns to another understated moment. Jethro observes Moses judging the people from morning until night, resolving even the smallest disputes. Concerned that the burden will crush his son-in-law, he urges him to delegate and to establish a network of judges. A judicial structure is put in place to support Moses and sustain the people. This, too, is a valuable lesson in governance and responsibility – but why does it stand at the threshold of Sinai?

Would it not have been more striking to open the section of Jethro with the thunder and fire of revelation itself? More iconic, more symbolic, to move directly into the moment when God speaks? Why does the Torah pause for these accounts of family welcome and legal organization before ascending to Sinai?

Fire and restraint

Mount Sinai marks the launch of religious faith. Hearing the voice of God fills human beings with passion, intensity, and awe. Religious energy surges, and zeal runs high after receiving the word of God.

But uncontained passion can drift into extremism. Religious intensity, when left unrestrained, can harden into radicalism. Lofty spiritual aims can tempt people to dismiss ordinary human conventions – moral restraint, social responsibility, even the rule of law. When standing in service of a transcendent God, human systems can begin to feel small or even expendable.

To prevent this danger, the Torah establishes two foundations before revelation. Jethro cares for Moses’ family while Moses is consumed with the liberation of our people in Egypt. Moses and the leaders pause, even in the harsh conditions of the desert, to receive Jethro with dignity and hospitality.

We are then shown legal structure. Jethro urges Moses to create a system of judges, embedding law, procedure, and accountability into the life of the people. Authority is shared, enforced, and made sustainable.

Only once these foundations are in place can Torah be given. The religious intensity of Sinai must be framed by moral discipline and respect for law and governance. Without that prior structure, Sinai’s fire could ignite passion that overwhelms ethical conduct and erodes the rule of law.

Life often feels clearest at the extremes. Choices appear binary, and the world is reduced to black and white, right and wrong, with an air of absolute confidence. When religion becomes radicalized, that certainty is amplified by the added force of faith. “God is on my side; I act as His agent. How could I be wrong?” Once framed that way, religious ends can be made to justify almost any means. The conviction of serving a higher purpose can license the erosion of ethical restraint and disregard for law.

Overriding norms

A stark illustration appeared in the 17th century with the rise of the false messiah Shabbetai Tzvi, who persuaded a vast portion of the Jewish world that redemption had arrived. Some of his followers embraced practices that openly violated Halacha (Jewish law), including the consumption of forbidden foods. If the messianic era had already begun, they argued, the old legal framework no longer applied.

This phenomenon – antinomianism – marks an extreme rejection of law, rooted in the belief that transcendent redemption overrides binding norms.

Whenever people are convinced that they are acting in the name of higher goals – especially when they believe they are serving God – moral boundaries become fragile. Human conventions, law, and ethical expectations begin to feel secondary, even obstructive, when set against the sweeping agenda they believe they are advancing. Often, they see themselves as voicing what others secretly feel but lack the courage to enact. In their own eyes, they are not violating norms: They are carrying the will of the collective – further than others dare.

Sovereignty and responsibility

We are witnessing forms of this dynamic today, especially within religious communities. In several settings, small but vocal extremist factions – often younger members – are acting in ways that disregard law and basic moral restraint in pursuit of deeply held ideological aims. In some cases, this has taken the form of disruptive protests that upend daily life for hundreds of thousands of citizens. At times, these demonstrations have turned violent, with tragic consequences. Such behavior often reflects a broader culture in which legal authority is treated lightly. Regrettably, the actions of a few are casting a shadow over entire communities, breeding alienation and resentment rather than advancing communal values.

In other communities, the aspiration to settle the land – an ideal we all share – has been expressed through violence directed at police, soldiers, and non-Jewish residents. Beyond the inherent danger of such acts, they drain precious manpower and attention from security forces at a time of acute national need. Every resource diverted to containing internal violence weakens our ability to defend the country.

These actions ultimately undermine the important cause they claim to serve, both practically – by portraying settlement efforts as violent and exclusionary – and spiritually, by betraying the expectation that we inhabit this land with respect for law, dignity, and human life.

In all these cases, religious passion, when severed from moral discipline and legal restraint, becomes destructive. A higher ideal is invoked, but ethical conduct and respect for law are trampled in its name.

Our tradition accords deep respect to institutions of law and governance. We are taught to pray for the welfare of the ruling authorities, even when they fall short of justice, because the alternative is chaos and anarchy. Alongside this, Judaism affirms basic human norms of decency and moral conduct.

Similarly, we are instructed to live with derech eretz – the “way of the land.” This term does not simply mean morality in the abstract: It refers to the shared human conventions of conduct, civility, and restraint that develop within society to allow people to live together with dignity. Our sages insist that derech eretz precedes Torah. Just as the courteous and respectful encounter between Moses and Jethro appears before the revelation at Sinai, the way of the land must come before full Torah commitment.

Respect for law is even more critical in Israel. We finally live with Jewish symbols of authority and governance. What earlier generations could only dream of – a society shaped by Jewish sovereignty, Jewish courts, Jewish police, and Jewish soldiers – has become reality. To mock, weaken, or attack these institutions is not an abstract failure; it is a betrayal of generations who lived without them and longed for their return.■

The writer, a rabbi at Yeshivat Har Etzion, was ordained by Yeshiva University and has an MA in English literature. His books include To Be Holy but Human: Reflections Upon My Rebbe, HaRav Yehuda Amital. mtaraginbooks.com.