Suddenly, March 28 – a mere four weeks ago – seems so distant.

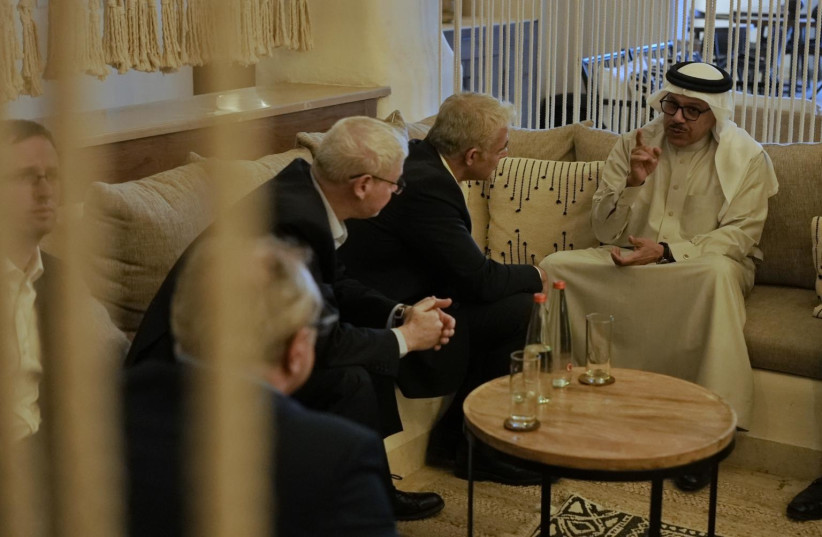

Remember March 27-28? That was when the foreign ministers of Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Morocco and Bahrain gathered – along with Foreign Minister Yair Lapid and US Secretary of State Antony Blinken – in the Negev for the first-ever meeting of this kind in Israel. And not just anywhere in Israel, but symbolically at Sde Boker, within walking distance of the grave of Israel’s founding father, David Ben-Gurion.

The Palestinians were not invited to this summit, nor is it clear whether they would have attended even had they been asked – they were adamantly opposed to the Abraham Accords that normalized relations between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, Morocco and, at least to some extent, Sudan.

Although each of the Arab foreign ministers, with the exception of the UAE, referenced the Palestinian issue in their remarks, this was by no means one of the central issues on the agenda.

The summit convened a couple of days after a lone-wolf terrorist attack in Beersheba, and the same evening of the lone-wolf terrorist attack in Hadera. Two other attacks, one in Bnei Brak and the other in Tel Aviv, were to follow shortly thereafter. The meeting took place before the IDF launched Operation Break the Wave to stem the rising tide of terrorism, and before the recent days of Palestinian-instigated violence on the Temple Mount.

The violence – rocks and cinder blocks being thrown by rioters on the Temple Mount last Friday at Jews worshiping at the Western Wall some 19 meters below – led to massive arrests and police entry into al-Aqsa Mosque.

The reaction from the Arab world was swift and predictable. Condemnations poured in from all over, including from the four Arab countries that took part in the Sde Boker meeting. Jordan summoned Israel’s chargé d’affaires to its Foreign Ministry for a dressing down, and a day later the UAE did the same to Israel’s ambassador there.

The Negev what?

If the Palestinians were insulted at being kept off the Negev Summit invitation list, if they were angry that their issue did not take center stage at that meeting, then the recent turn of events could be aptly called Mahmoud Abbas’s revenge.

“You didn’t put us on the agenda,” the Palestinians seemed to be saying, “but we know how to get back on the agenda.”

And they do – through violence. It is amazing what some terrorism and spreading the “al-Aqsa is in danger” lie can do to get the spotlight back on the Palestinian cause.

THIS RECENT bout of tension was not the first test of the Abraham Accords: that first test came during last year’s Operation Guardian of the Walls, which – like the recent events – was preceded by tension and violence in Jerusalem and on the Temple Mount.

Then, too, the Abraham Accords states reflexively condemned Israel’s actions to quell the violence on the Temple Mount. But, interestingly, when the focus went from Jerusalem to the war against Hamas in Gaza, the condemnations were neither as loud nor as frequent, attributable to the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco not shedding any tears when the Muslim Brotherhood-linked Hamas is pounded and their capabilities significantly downgraded by Israel.

According to an Institute for National Security Studies paper written shortly thereafter, the accords themselves were not significantly damaged by that round of violence, despite a slowdown in momentum and there being some postponements of civil society events.

This did not, however, translate into the recall of ambassadors or the cancellation of any agreements. The government-to-government contacts and intelligence and security cooperation continued. Operation Guardian of the Walls proved little more than a hiccup, and a hiccup all surely knew would happen from time to time when they signed the accords in September 2020.

Will this time be any different? Probably not, as long as the violence surrounding the Temple Mount does not go on too long or lead to too many Palestinian casualties.

NEVERTHELESS, ISRAEL needs to learn some lessons from the current round and try to alter the seemingly built-in reflex whereby no matter what happens on the Temple Mount, no matter what the Palestinians do to provoke, the Arab world will overlook the provocations that triggered an Israeli response, and will buy the lies that Israel is attacking innocent worshipers and is on the verge of allowing animal sacrifices on the site or are about to divide the prayer space there between Jews and Muslims, just as is the case in the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron.

One of the most liberating aspects of the Abraham Accord was the way that the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco mustered the courage to unlink their interests from Palestinian maximalist demands.

Their new equation was simple: We have an interest in dealing with Israel, and there is no reason that those interests should be held hostage by Palestinian behavior. In this new way of thinking, those states were saying that if the Palestinians want to take an uncompromising position toward Israel, that is their business, but that these states have their own reasons for wanting a relationship with Israel – economic reasons, reasons having to deal with Iran and with the US – and these reasons do not have to be mortgaged to Palestinian demands.

The courage these countries demonstrated in decoupling their ties with Israel from the Palestinian issue, they have been unable or unwilling to show when it comes to seasonal violence on the Temple Mount. While by signing the Abraham Accords they showed they were not going to let Palestinian negotiation demands keep them from dealing with Israel, they are willing to let Palestinian provocations on the Temple Mount throw some shade over their ties with Jerusalem.

These countries, with sophisticated intelligence apparatuses and not dependent on TikTok for their information, surely know what is happening on the Temple Mount.

They surely know that the Israel Police did not barge unprovoked into al-Aqsa, but, rather, went in there to apprehend rioters who, as it often turns out, gathered rocks and cinder blocks there to have them ready for confrontation.

They also must surely know that Israel has, over the last 55 years, never allowed any pre-Passover sacrifice on the Temple Mount, and had no intention of doing so this year, nor does it have any intent to divide the mosque and turn half of it into a synagogue.

But if they don’t know, then Israel should be giving them the intelligence information showing them without a doubt what is truly happening at the site.

Much has been made of the burgeoning security and intelligence cooperation that exists between Israel and these countries, and there has even been talk of intelligence they share about sensitive subjects such as Iran. So if they can share that kind of intel, then surely Jerusalem can share intelligence evidence showing this week’s violence was not a spontaneous combustion, but was planned in advance with the desired result being to trigger an Israeli reaction that would lead to an even larger conflagration.

WHILE IN the past Israel’s public diplomacy efforts concentrated on trying to get the Western democracies to see the true picture of events happening on the Temple Mount, now that effort needs to be focused more on the Abraham Accord countries.

What a game-changing act of courage would it have been had Bahrain, Morocco or the UAE, instead of calling in the Israeli ambassador for a reprimand, posted extant videos of Arab youth in the mosque surrounded by rocks ready to hurl, with their shoes on and kicking around a football, above the following tweet: “They desecrate mosques in their filth and turn the mosques of Allah into a playground under the pretext of resistance.”

That tweet, by the way, was a real one posted last week by a Saudi cartoonist who drew a cartoon of the desecration taking place inside the mosque.

Likewise, in the UAE, Kahlid bin Thani, a man with some 50,000 Twitter followers who describes himself as a “social media influencer,” posted a picture of two men, both of them wearing shoes and one wrapped in a Hamas flag, in front of a pile of stones and cinder blocks inside al-Aqsa.

“Always look for Hamas and groups trading in religion,” he tweeted in Arabic. “Pay attention to the amount of rocks inside the mosque without any respect for it, to carry out acts of sabotage and cause a riot to drag the other side into a confrontation and then to wave the slogans ‘incursion into al-Aqsa’ and ‘attacks on worshipers.’”

In other words, not everyone in the Arab world is buying the Palestinian propaganda; some are seeing through it. If only a government such as the UAE would do something similar, it could have a significant impact.

But that type of turn, much like the Abraham Accords themselves, is not going to happen by itself or overnight. An intense campaign needs to be undertaken to make it happen, as well as an articulated Israeli expectation that these countries do not just fall back into their regular patterns.

Those who believe that it may be impossible to ever break this particular pattern, since support for the Palestinians in Arab public opinion is so great, and al-Aqsa Mosque is such an emotive issue, should look at the response this week to the events by Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Yes, Erdogan, who during last year’s violence on the Temple Mount had this to say: “Israel, the cruel terrorist state, attacks the Muslims in Jerusalem – whose only concern is to protect their homes... and their sacred values – in a savage manner devoid of ethics.”

He then went on to say that the violence on the Temple Mount was “an attack on all Muslims,” and added that “protecting the honor of Jerusalem is a duty for every Muslim.”

That was last year. This year, amid his campaign to normalize ties with Israel because it serves Turkish interests, he sang a completely different tune. Following a phone call on Tuesday with President Isaac Herzog, Erdogan’s office issued a statement saying the two discussed “the bilateral relations and regional issues, particularly the incidents some Israeli radical groups and security forces have recently used in Palestine.”

The complete statement was by no means a paean to Israel, but it was also very far from the anti-Israeli and even antisemitic rhetoric Erdogan has used against Israel during similar circumstances in the past.

And if Erdogan can change his rhetoric when it comes to the Temple Mount, so can the UAE, Bahrain and Morocco.

If they do, if they actually start to question out loud the Palestinian narrative of events there every year and look at what precipitates the violence, and if they’d respond to what is actually happening, rather than to lies and fabrications, then the Palestinians may eventually realize that shouting “al-Aqsa is in danger” no longer has the desired effect.

And if that ever happens, then someday they may stop using it as an excuse to provoke violence at the site year after year after year.