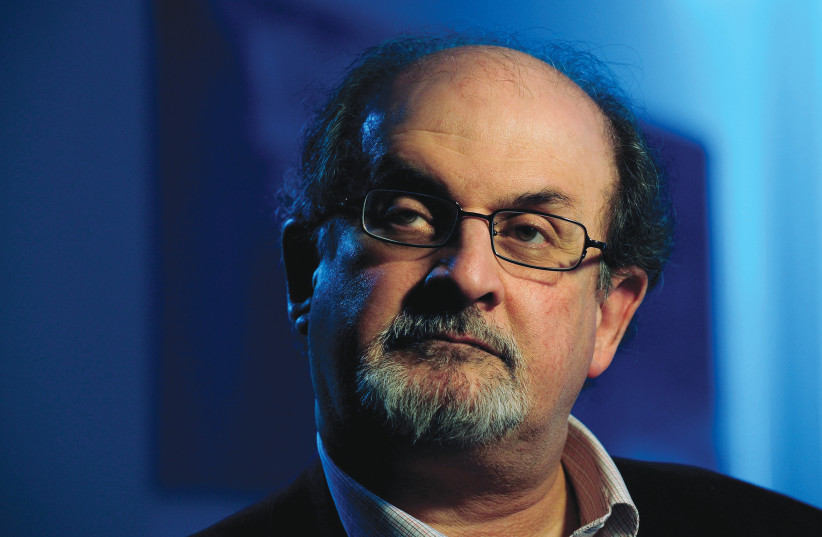

Iranian regime and pro-Iranian media outlets reacted with enthusiasm to the attempted murder of British-Indian author Salman Rushdie last week. Officials of the Islamic Republic of Iran have maintained a studious silence. But the main mouthpieces of both the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), and the various Shia militia franchises that the IRGC maintains throughout the Arabic-speaking world, have been open in their support for the would-be assassin, 24-year-old Hadi Matar, and for the attempt on Rushdie’s life.

The emerging facts regarding the process by which Matar was radicalized, meanwhile, showcase the extent to which the Shia Islamist archipelago that surrounds Iran resembles in significant ways the Sunni Islamist world. It is customary among analysts of political Islam to draw a sharp distinction between the centralized, organized and hierarchical world of the IRGC and its various franchises, and the more chaotic and self-starting landscape of Sunni radicalism. Matar’s case shows that this distinction is not entirely tenable.

The central difference between the two is the presence of a state, with the full capacities deriving from that, in the Shia case. But many of the features which characterize those young Western-born Sunnis who were drawn to support and act on behalf of ISIS or other similar groups over the last decade appear to be present also in the case of Rushdie’s would-be assassin.

Regarding the support for Matar’s act in pro-Iran outlets, the Telegram channel of al-Sabereen, a media organization associated with Iraq’s Shia militias, wrote that “It is noteworthy that the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Republic of Iran, Sayyid Khomeini, issued a fatwa on the spilling of Rushdie’s blood because of his famous novel The Satanic Verses and his insult to the verses of God,” before going on to refer to Matar as “the implementer of the fatwa of Sayyid Khomeini.”

Al-Sabereen responded to the announcement of the identity of the would-be murderer and the emergent evidence of his pro-Iranian affiliations with a Shia blessing expressing thanks to God. Elsewhere, the channel headlined its coverage of the attempted murder under the title “The Revenge of God.”

In Farsi-language outlets directly associated with the IRGC and the Iranian regime, the Kayhan newspaper wrote in its Sunday editorial that “God has taken his revenge on Rushdie.” The Tasnim website, which reflects IRGC positions, meanwhile, described Rushdie as “the apostate author of the book Satanic Verses, who had insulted Islam’s sacred realm, the Quran and the beloved Prophet of Islam.”

Tasnim on August 14, in its Farsi section, carried an interview with Sa’adullah Zarei, whom it described as a “senior expert and political analyst.” In the interview, Zarei asserted that “Naturally, as a Muslim person or as a Muslim country, we welcome and rejoice in the destruction of Salman Rushdie, in whatever form it takes... this person should be annihilated due to the serious and very major crime he committed.”

These sentiments reflect the uncontroversial and accepted opinion in the pro-Iran, Shia Islamist milieu, according to which the February 1989 fatwa of Iranian Supreme Leader Sayyid Ruhollah Khomeini, advocating Rushdie’s killing, remains in effect, and hence its attempted implementation is to be welcomed.

How did Matar get to this point?

MATAR’S PATH toward becoming the would-be “implementer” of Khomeini’s fatwa is less immediately clear. Born in the US to parents who emigrated from the Shia, south Lebanese town of Yaroun, Matar was raised in California and New Jersey. His Facebook account, as published in US media (and republished with added celebration by al-Sabereen), shows support for the IRGC and the Iranian regime.

When arrested, Matar was carrying a fake driving license in the name of “Hassan Mughniyeh.” While constituting a regular Arabic name, this is also an amalgam of the names of two of the heroes in the pantheon of the IRGC and its Arab franchises – Lebanese Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, and Imad Mughniyeh, military mastermind of the same organization.

Matar, according to an interview with his mother, Silvana Fardos, by the British Daily Mail newspaper, became radicalized following a visit to south Lebanon in 2018. His father, Hassan Matar, is a resident in the town of Yaroun, and Hadi Matar stayed in the area for 28 days. Yaroun is in an area controlled by Hezbollah. On his return, Matar remained focused on his new interest in Islam, according to the interview.

At some point between this visit and the attack on Rushdie, it is likely that Matar was in contact via social media with elements “either directly involved with or adjacent to” the IRGC and the Quds Force, its external wing, according to unnamed “mid-Eastern intelligence officials” quoted in a report at Vice News.

The veracity of such claims remains to be established. And it should be noted in this regard that the unnamed officials cited by Vice do not assert clearly that the attack was initiated and directed by Iran and the IRGC. Rather, they suggest a range of possibilities.

These would include that Matar was indeed controlled and directed by IRGC/QF officials, or that he was in contact with such figures who might have helped in his radicalization. There is also the possibility that Matar was simply inspired by the messages emanating from the Iranian regime’s extensive online activity, and then decided independently to act upon them.

But even if one takes the most minimalist interpretation of the currently available evidence, according to which Matar was “self-radicalized” online following his visit to Lebanon, the picture that emerges is a striking one, at once familiar and new.

Familiar – because the trajectory by which a Western-born or -raised young man or woman comes across political Islam through online activity or chance acquaintance, and is then drawn into deeper engagement with it, and finally becomes a soldier in its cause is one by now well known in the West.

Figures of this kind have been behind many of the most notorious acts of Islamist terror in recent years. The Hyper Cacher attack in 2015, the torture and execution of Western journalists and aid workers by ISIS in the 2014-19 period, and the 2013 bombings at the Boston Marathon, were all carried out by individuals of this type. They are part of a much longer list.

But striking, because unlike in the aforementioned cases, in the case of Matar’s attempt on the life of Rushdie, the outlets and messages and indoctrinators were all operating in the service of a state. Not an improvised arrangement like the short-lived “Islamic State,” but a recognized, legal entity with a seat at the UN General Assembly.

This ability to navigate between the realms of conventional statehood and paramilitary and terrorist organization is the largest force multiplier possessed by the Islamic Republic of Iran. Across the Arabic-speaking world, it is this capacity, above all others, that has brought Tehran to its achievements of the last decade.

As should now be apparent, this combination extends to activity on the soil of Western states too. This, with all its implications, needs now to be internalized by Western governments. The knife that struck Salman Rushdie at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York may have been Matar’s – but the operating hand behind it was that of Iran.