Tradition Today: The two loves of Hillel

Hillel’s teaching may be 2,000 years old, but it has not lost its meaning and its importance.

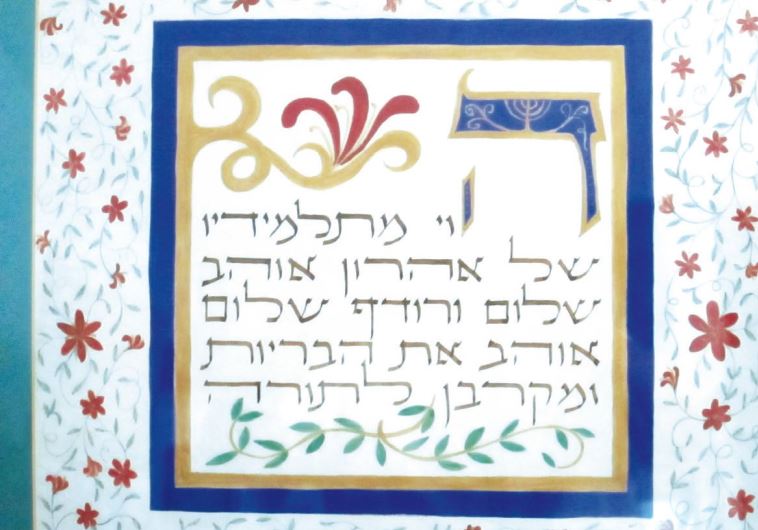

The plaque designed by the author’s wife with his favorite rabbinic saying by Hillel(photo credit: COURTESY OF RAHEL HAMMER)

The plaque designed by the author’s wife with his favorite rabbinic saying by Hillel(photo credit: COURTESY OF RAHEL HAMMER)