The apparent suicide of Chaim Walder and the subsequent revelations about his alleged sexual crimes continue to send shock waves throughout the Jewish world.

The haredi population, in particular, has struggled mightily to come to terms with this bitter reality.

While sex scandals are not unknown in any society, Walder – through his best-selling series of books over the course of many years – deeply influenced an entire generation of children and endeared himself to innumerable families.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons that many leaders in the haredi world are slow in condemning Walder, with some stubbornly refusing to believe that he could possibly have been the monster that numerous testimonies make him out to be. There are publications that glaringly omit the story of his apparent suicide, while others persist in claiming his innocence, even referring to him as a tzaddik, a righteous person unfairly maligned.

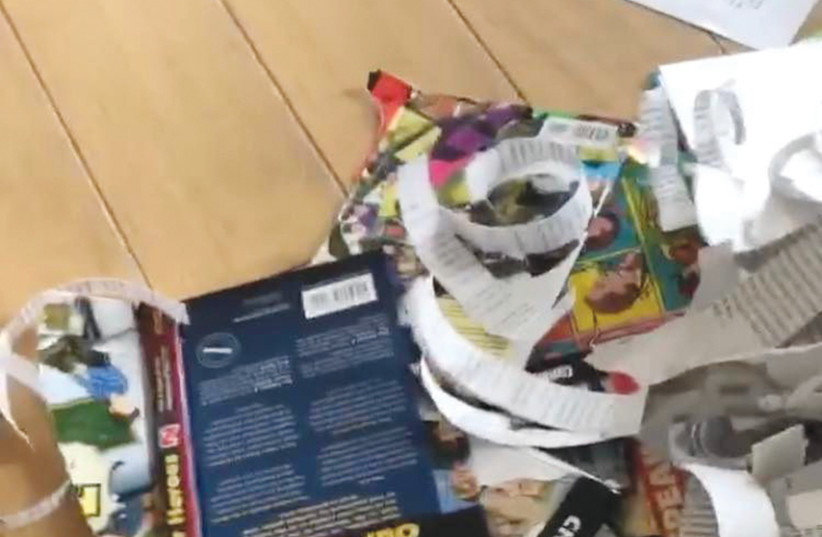

And then there are those who have gone the other way, removing his books from the shelves, forbidding their children from reading them, even burning them publicly and sharing the moment on video so that others might do the same.

But let’s stop for a moment and consider this: Are we required to negate and denigrate both the actions and the achievements of everyone who is outed? Do their crimes unalterably obliterate their accomplishments, or are they somehow redeemable? In short, is it possible to separate the sins from the sinners?

THIS MORAL conundrum has confounded ethicists and philosophers for centuries, and has been the subject of untold debates. Many of the most powerful and penetrating cases in recent history came in the aftermath of the Holocaust.

Nazi scientists used countless inmates of concentration camps as human guinea pigs in conducting grotesque medical or psychological experiments.

One of these experiments was their attempt to determine how long people could survive in situations of extreme cold.

Their purpose, ostensibly, was to establish the most effective treatment for victims of immersion hypothermia, particularly crew members of the German Luftwaffe who had been shot down into the cold waters of the North Sea.

Inmates were held for hours in tanks of bitterly cold water or left standing naked in freezing weather. Some were frozen to death in attempts to learn just how much cold a human being could endure before expiring; others were brought near to death, then subjected to warming techniques, such as hot baths or body heat transference from female prisoners to assess the possibility of recovery.

After the war, there was an acrimonious debate about using this information, which was deemed – precisely because of its cruel disregard for the victims – to be more accurate than any other existing data on the subject.

Some argued, in the interest of science and for the good of humanity, that it should be used, that it was critical in the effort to improve methods of reviving people rescued from freezing water after boat accidents.

Others, appalled by the source of the material, would have no part of it; the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, refused to publish the data openly.

WHAT WOULD Judaism say?

We have numerous examples of evil people who perpetrated horrendous atrocities upon the Jewish people and yet were cited for their positive contributions.

Balaam, for example, is referred to in rabbinic literature as “the wicked one” and was executed for his crimes, yet his prophecies are recorded at length in the Torah. In fact, to this day our morning prayers commence with a blessing he uttered, “Ma tovu ohalecha, Yaakov” (how goodly are your tents, Jacob).

Pharaoh presided over the century-plus enslavement of the Israelites, perhaps the greatest tragedy in our history until the Shoah (Rashi, the greatest of commentators, maintains that 80% of the Jewish population was wiped out during this period). But not only did Pharaoh survive the plague of the death of the firstborn – despite his being a firstborn himself – but he went on, say some authorities, to become king of Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, and convinced its population to reform its immoral ways.

Then there is Laban – certainly no laudatory figure – who is the source of the custom of Sheva Brachot, the weeklong post-wedding celebration of bride and groom that is followed by Jewish communities everywhere until today.

A famous Talmudic story provides a proof text of the difference between sins and sinners: Neighborhood thugs were making life miserable for Rabbi Meir, and so he decided that drastic measures were called for. He began to pray that the ruffians would die, until his brilliant wife, Bruriah, stopped him. She quoted to her husband the verse in Psalm 104, “banish the sins, and the wicked will be no more.” “Rather than pray that these thugs should die,” she argued, “you should pray that they repent, and then the wickedness will disappear.” He listened to her, he prayed, and they stopped.

In a famous passage in Ethics of the Fathers (6:3), the rabbis proclaim that we are obligated to show honor to anyone who teaches us a single Torah law, or even a single letter of the Torah. In illustration, King David is cited as showing deference to Ahitophel, his once-trusted adviser who conspired against him and incited David’s son Absalom to rebel against the monarchy. The Talmud states that Ahitophel – who committed suicide by hanging himself – is one of the few individuals in history who was denied entry to the World to Come, due to his high crimes.

Who in this world, to be honest, is truly innocent? Moses and Aaron both sinned when they struck the rock; Jacob sins when he fools his father. King David also is held to account for sending Uriah to the front so that he could take Bathsheva. David’s son Solomon succinctly sums it up (Ecclesiastes 7:20): “There is no person on Earth who does only good and never sins.” And so, logically, if we are to hate all those who sin, then in effect we must hate everyone!

Judaism makes it clear that God keeps a perfect account of our every action and responds with Divine accuracy; each meritorious act will create a positive reaction in its wake, while each sin brings its own negative consequence. It’s not a zero-sum game; we have to acknowledge both sides of the ledger.

Society – particularly those who aspire to lead it – must unequivocally condemn those who prey upon the innocent and do harm to others. Our first and foremost concern must always be for the victims; we must be sensitive to their feelings and responsive to their pain and suffering. As for the victimizers, we must refrain from whitewashing their abuses and hold them to full account for their crimes.

Yet, at the same time, we needn’t destroy what they have built or dismiss the good they may have created. A murderer who wishes to donate an organ that will save another life should not be refused – nor should his just punishment be withheld.

For better or worse, we live in a complex world where the traits of good and evil, compassion and cruelty, often dwell together, and we need to know how to properly respond to each one of them. ■

The writer is director of the Jewish Outreach Center of Ra’anana. jocmtv@netvision.net.il