As a result of Hamas’s brutal massacre of over 1,300 Israelis on October 7, Gaza has once again been thrust back into the international spotlight, garnering attention across the globe.

And while much has been said about this strip of land along the Mediterranean Sea, it appears that few are aware of its long and vivid history, which is inextricably linked with that of the Jewish people and contains within it some lessons relevant to our current situation.

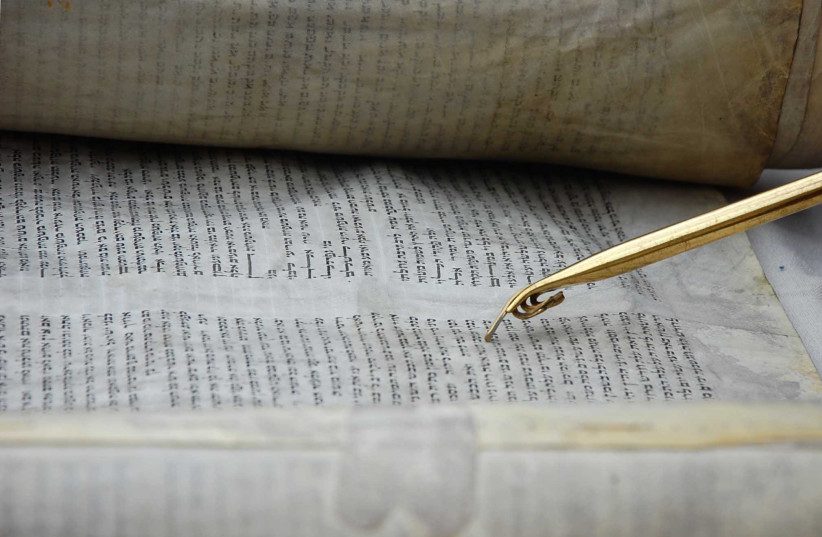

Indeed, the Jewish connection with Gaza stretches back to the dawn of our very existence.

Jews have been in Gaza since the very beginning of Judaism

According to the Bible, two of our nation’s founding fathers, Abraham and Isaac, sojourned in Gaza. In the Book of Genesis (20:1), the Torah says that Abraham “lived in Gerar,” a city in Gaza.

Later, when there was a famine in the land and Abraham’s son Isaac thought of leaving for Egypt, God stopped him in Gerar and told him explicitly: “Dwell in this land, and I will be with you, and I will bless you; for unto you and unto your seed will I give all these lands” (Genesis 26:3).

Isaac remained in Gaza, and it is precisely there – in Gaza, of all places! – that God saw fit to reaffirm His covenant with the Jewish people to grant them the entire Land of Israel.

Centuries later, after the Exodus from Egypt, when the Jews finally reached the Promised Land, Gaza was given to the tribe of Judah (see Joshua 15:47) as a share of its inheritance; and according to the Book of Judges (1:18), “Judah captured Gaza and its border.”

Nonetheless, the hostile Philistines continued to maintain some level of control over part of the area, serving as a thorn in the side of Israel. Sound familiar?

Later, in 145 BCE, some two decades after the liberation of the Temple in Jerusalem and the miracle of the Hanukkah oil, the Hasmonean king Jonathan, the youngest of Matityahu’s five sons, attacked Gaza and its hostile population.

As the historian Josephus writes in his Antiquities of the Jews (volume 13, 5:5), Jonathan “set a part of his army round about Gaza itself, so with the rest he overran their land and spoiled it, and burned what was in it. When the people of Gaza saw themselves in this state of affliction... they went to Jonathan and professed they would be his friends, and afford him assistance.”

In other words, Jonathan conquered the area, pacified the populace, and compelled the Gazans to plead for peace.

Nonetheless, despite the assurances they gave, Gaza’s residents continued to agitate against Israel, leading Simon the Maccabee, who had succeeded Jonathan, to conclude what his brother had started.

As recounted in the First Book of Maccabees, Simon’s soldiers entered Gaza City, which led the local populace to “cry with a loud voice beseeching Simon to grant them peace.” They implored the Maccabee: “Deal not with us according to our wickedness but according to your mercy.”

Simon agreed, but not before taking a series of measures to try to ensure that Gaza would never again pose a threat.

Among these, he “placed such men there as would keep the law, and made it stronger than it was before,” essentially reimposing security on the unruly strip of land. Simon also sent Jews to settle the area, and he even built himself a home in Gaza, as if to underline the fact that the Jewish people had every intention of remaining.

But even these measures did not quell the problematic behavior of Gaza’s population.

It was only when Alexander Jannaeus, Matityahu’s great-grandson, captured the city in 100 BCE that the threat was finally ended and the southwestern border of the Hasmonean Jewish state enjoyed some long-sought peace. Alexander, Josephus tells us, “had utterly overthrown their city... having spent a year in that siege.”

Then, as now, Gazans claimed to want peace but continued to attack Israel. And then as now, limited military operations only brought short-term quiet, until the Jewish state at last decided to assert full control over the area.

Subsequently, during the Talmudic era, Gaza was home to a large Jewish population and served as a major port of commerce. In Sotah (20b), the Talmud mentions a rabbi named Eliezer son of Yitzhak whom it refers to as a man of Kfar Darom, a city in Gaza.

In fact, one of the oldest synagogues ever found in the Land of Israel is in Gaza, and it dates back to the early sixth century, more than 1,400 years before Hamas or the PLO were founded.

In 1965, on the outskirts of Gaza City near the sea, Egyptian archaeologists discovered a mosaic floor from the synagogue. It measured 3 meters by 1.8 m. and depicted King David playing a lyre, with his name written clearly in Hebrew.

During the Middle Ages, Gaza was home to a thriving Jewish community, including in the city of Rafiah, where Jews flourished for nearly 300 years until the arrival of the Crusaders in the 12th century. The Crusaders brutally destroyed the city and left it in ruins. A number of Jewish relics from this period, such as letters and correspondence by community members, were later found in the Cairo Genizah.

Gaza also boasted its share of prominent rabbis who left a lasting imprint on Judaism. These include Rabbi Yisrael Najara, author of “Kah Ribbon Olam,” the popular hymn sung in Jewish homes around the world every Shabbat. He served as Gaza’s chief rabbi until his death in 1625, and he was buried in the city’s Jewish cemetery. Yes, Gaza had an ancient Jewish cemetery.

The great medieval Kabbalist Rabbi Avraham Azoulai also lived in Gaza, where he authored his famed work, Hesed L’Avraham, along with a commentary on the Bible.

After the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and Portugal at the end of the 15th century, a number of the exiles made their way to Gaza, where members of the Jewish community worked in various trades, such as merchants, silversmiths, and farmers.

And lest there be any doubt in anyone’s mind, Gaza is considered to be part of the Land of Israel. This is attested to by Nahmanides and Rabbi Hayim ibn Attar, the Or Hahayim, in their commentary on Genesis 26:3.

In the 18th century, the great scholar Rabbi Yaakov Emden ruled that Gaza is an intrinsic part of the Jewish people’s national heritage. “Gaza and its environs are absolutely considered part of the Land of Israel without a doubt,” he wrote in his work Mor U’ketziya, adding, “There is no doubt that it is a mitzvah to live there, as in any part of the Land of Israel.”

It is perhaps due to the Jewish people’s deep roots in Gaza that despite having been expelled from the Strip seven times over the past 2,000 years, they always sought to return. In 61 CE, the Romans evicted the Jews from Gaza, as did the Crusaders, Napoleon, the Ottoman Turks, the British Army in 1929, and the Egyptians in 1948.

And then, in 2005, Israel’s own government joined the ignominious list of those who sought to bring about an end to the Jewish presence in Gaza when it uprooted Gush Katif and other Jewish communities in the area.

As this brief historical outline demonstrates, Gaza’s Jewish history has been one of triumph and tragedy, exile and return, mirroring that of the Jewish people as a whole. But however far-fetched it might sound right now, the dream of a Jewish Gaza has not been quashed. Gaza is not only part of Jewish history, it is also linked with our destiny.

In his commentary on Genesis 26:23, the medieval French Rabbi David Kimhi, who lived 800 years ago and is known as the Radak, presciently wrote that the Jewish people would not hold on to Gaza without controversy or strife, but that eventually, in the messianic era, the strip of land would entirely be ours.

May it happen speedily and in our days. ■

The writer served as deputy communications director under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.