Forty-eight years ago yesterday, on October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a surprise attack on Israel, triggering the Yom Kippur War, an earthquake whose aftershocks would rattle Israel and the region for decades.

Despite Israel quickly regaining its footing and position three weeks later within striking distance of both Cairo and Damascus, that war punctured the country’s aura of invincibility.

The country suddenly viewed itself, and was viewed by its enemies, as vulnerable, a perception that shaped both Israel’s policies and the policies of others toward it for years to come.

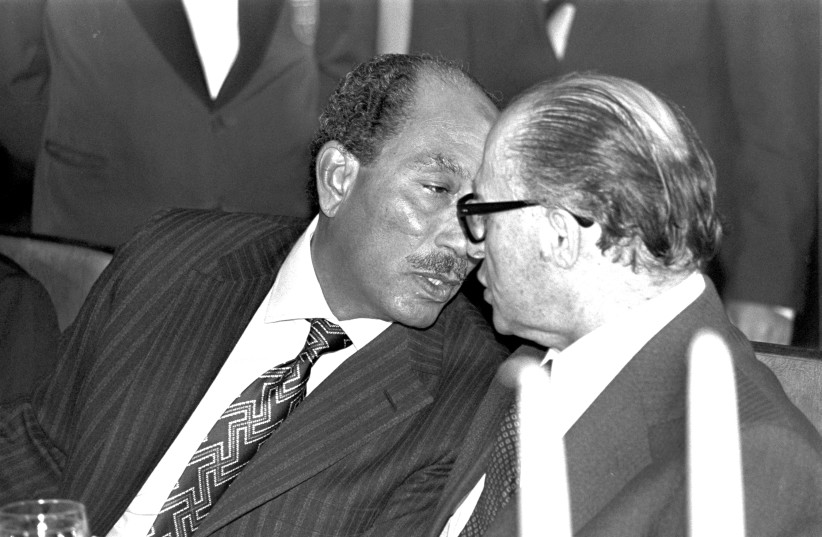

But October 6 is not only the anniversary of the Yom Kippur War. On that same day eight years later – in fact, at a military parade in Cairo commemorating what is still viewed in Egypt as a great victory – Islamic radicals gunned down Egyptian president Anwar Sadat.

That event, too, was an earthquake whose aftershocks are still rattling the region, but one that is often viewed through too narrow a lens, as “merely” a reflection of hatred toward Israel and fierce opposition to Sadat’s signing a peace treaty with Israel in 1979.

Sadat’s assassination certainly did reflect those two fiercely anti-Israel sentiments, but there was more to it than that. His assassination was also a natural extension of what erupted in Iran two years earlier, when Ayatollah Khomeini deposed the shah and ushered in the Islamic Republic; of the seizure of the Grand Mosque in Mecca by Islamic radicals that same year, which led to the deaths of hundreds; and of the process of Islamization that was altering Pakistan.

The Sadat assassination was obviously about Israel, but not only about Israel. It was also a graphic manifestation of this radical, violent Islam that fundamentally rejected the West. It was a portent of much worse things to come.

As the journalist Kim Ghattas wrote in her 2020 book, Black Wave, chronicling the “rivalry that unraveled the Middle East” between Iran and Saudi Arabia, at the time of Sadat’s assassination there were those in Egypt who were “in awe of the Iranian revolution, mesmerized by the masses on the street and the sight of people power at work, bringing down a tyrant, a traitor to.... [their] people and to Palestine.”

In other words, what happened in Iran did not stay in Iran. The 1979 Iranian revolution unleashed a radicalization of Islam and provided a strong tailwind to the violent Islamists who killed Sadat and continue to roil the region.

The first foreign leader to visit Tehran after the revolution and meet with Khomeini in 1979 was PLO head Yasser Arafat, who did so while Egyptian and Israeli officials were working on a peace deal at Camp David. Arafat and Khomeini forged strong ties that continue to this day between Palestinian terrorists and Tehran.

Among the leaders of the cell to which Sadat’s assassins belonged was Ayman al-Zawahiri. Sadat is gone, but Zawahiri is still here, now thought to be the head of al-Qaeda, an organization he helped form. The Egyptian president who wanted to reorient his country away from the Soviet Union and toward the US and who wanted peace with Israel is no more, while the person who rejected all that still fights on 40 years later.

Sadat’s assassination, unlike – for instance – John F. Kennedy’s killing, was not a one-off deal, but part of a larger, pernicious trend that has poisoned, and continues to poison, the region.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that there is another camp in the region, a camp Sadat gave birth to and which – though it seemed stagnant for much of the last four decades – has recently picked up steam thanks to the Abraham Accords. This is a camp that embraces modernity and peace with Israel.

On the 40th anniversary of Sadat’s assassination, at a time when some want to throw a lifeline to an Iran still shaped in Khomeini’s image in order to get it back into the 2015 nuclear deal, it is incumbent upon the world, led by the US, to contemplate Sadat’s legacy; not only what he did in forging peace with Israel, but also how to keep those forces that killed him – forces that then, as now, gained inspiration from Iran – from getting stronger.